This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

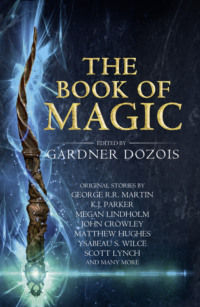

Read the book: «The Book of Magic: A collection of stories by various authors»

Copyright

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager 2018

Copyright © 2018 by Gardner Dozois

Introduction © 2018 by Gardner Dozois

Individual story copyrights appear here

Cover design by Mike Topping © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

The author of each individual story asserts their moral rights, including the right to be identified as the author of their work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

These stories are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in them are the work of the authors’ imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008295806

Ebook Edition © October 2018 ISBN: 9780008295813

Version: 2018-09-21

Copyrights Acknowledgements

“The Return of the Pig” by K. J. Parker. Copyright © 2018 by K. J. Parker.

“Community Service” by Megan Lindholm. Copyright © 2018 by Megan Lindholm.

“Flint and Mirror” by John Crowley. Copyright © 2018 by John Crowley.

“The Friends of Masquelayne the Incomparable” by Matthew Hughes. Copyright © 2018 by Matthew Hughes.

“Biography of a Bouncing Boy Terror, Chapter II: Jumping Jack in Love” by Ysabeau S. Wilce. Copyright © 2018 by Ysabeau S. Wilce.

“Song of Fire” by Rachel Pollack. Copyright © 2018 by Rachel Pollack.

“Loft the Sorcerer” by Eleanor Arnason. Copyright © 2018 by Eleanor Arnason.

“The Governor” by Tim Powers. Copyright © 2018 by Tim Powers.

“Sungrazer” by Liz Williams. Copyright © 2018 by Liz Williams.

“The Staff in the Stone” by Garth Nix. Copyright © 2018 by Garth Nix.

“No Work of Mine” by Elizbeth Bear. Copyright © 2018 by Elizabeth Bear.

“Widow Maker” by Lavie Tidhar. Copyright © 2018 by Lavie Tidhar.

“The Wolf and the Manticore” by Greg van Eekhout. © 2018 by Greg van Eekhout.

“A Night at the Tarn House” by George R.R. Martin. Copyright © 2009 by George R.R. Martin. First published in Songs of the Dying Earth, edited by George R.R. Martin and Gardner Dozois.

“The Devil’s Whatever” by Andy Duncan. Copyright © 2018 by Andy Duncan.

“Bloom” by Kate Elliott. Copyright © 2018 by Kate Elliott.

“The Fall and Rise of the House of the Wizard Malkuril” by Scott Lynch. Copyright © 2018 by Scott Lynch.

Dedication

For

All those who work magic with words,

the most potent magic there is

Gardner Dozois 1947–2018

As an editor, Gardner had no peers. He discovered and nurtured more new talents than I could possibly remember or recount, myself included. It’s no exaggeration to say that I would not be where I am today if Gardner had not fished me out of the slush pile in 1970. He found me in his first editorial job, reading submissions at Galaxy, where he came upon my short story ‘The Hero’ and passed it along to the editor with a recommendation to buy. That was my first professional sale.

He was also the warmest, kindest, gentlest soul you’ll ever meet, larger than life, bawdy, funny … so funny. It was an honour to know him, and to work with him. I miss him so much.

George R.R. Martin, 2018

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Copyright Acknowledgements

Dedication

Gardner Dozois 1947–2018

Introduction by Gardner Dozois

The Return of the Pig by K. J. Parker

Community Service by Megan Lindholm

Flint and Mirror by John Crowley

The Friends of Masquelayne the Incomparable by Matthew Hughes

Biography of a Bouncing Boy Terror, Chapter II: Jumping Jack in Love by Ysabeau S. Wilce

Song of Fire by Rachel Pollack

Loft the Sorcerer by Eleanor Arnason

The Governor by Tim Powers

Sungrazer by Liz Williams

The Staff in the Stone by Garth Nix

No Work of Mine by Elizabeth Bear

Widow Maker by Lavie Tidhar

The Wolf and the Manticore by Greg Van Eekhout

A Night at the Tarn House by George R.R. Martin

The Devil’s Whatever by Andy Duncan

Bloom by Kate Elliott

The Fall and Rise of the House of the Wizard Malkuril by Scott Lynch

About the Publisher

Introduction by Gardner Dozois

Sorcerer, witch, shaman, wizard, seer, root woman, conjure man … the origins of the magic-user, the-one-who-intercedes-with-the-spirits, the one who knows the ancient secrets and can call upon the hidden powers, the one who can see both the spirit world and the physical world, and who can mediate between them, go back to the beginning of human history—and beyond. Fascinating traces of ritual magic have been unearthed at various Neanderthal sites: the ritual burial of the dead, laid to rest with their favorite tools and food, and sometimes covered with flowers; a low-walled stone enclosure containing seven bear heads, all facing forward; a human skull on a stake in a ring of stones … Neanderthal magic.

A few tens of thousands of years later, in the deep caves of Lascaux and Pech Merle and Rouffignac, the Cro-Magnons were practicing magic too, perhaps learned from their vanishing Neanderthal cousins. Deep in the darkest hidden depths of the caves at La Mouthe and Les Combarelles and Altamira, in the most remote and isolate galleries, the Cro-Magnons filled wall after wall with vivid, emblematic paintings of Ice Age animals. There’s little doubt that these cave paintings—and their associational phenomena: realistic clay sculptures of bison, carved ivory horses, the enigmatic “Venus” figurines, and the abstract and interlacing paint-outlined human handprints known as “Macaronis”—were magic, designed to be used in sorcerous rites, although how they were meant to be employed may remain forever unknown. These ancient walls also give us what may be the very first representation of a wizard in human history, a hulking, shaggy, mysterious, deer-headed figure watching over the bright, flat, painted animals as they caper across the stone.

So Magic predates Art. In fact, Art may have been invented as a tool to express Magic, to give Magic a practical means of execution—to make it work. So that if you go back far enough, artist and sorcerer are indistinguishable, one and the same—a claim that can still be made with a good deal of validity to this very day.

Stories about magic go back a similar distance, probably all the way back to when Ice Age hunters huddled around a fire at night, listening to the beasts who howled in the inky blackness around them. By the time that Homer was telling stories to fireside audiences in Bronze Age Greece, the tales he was telling contained recognizable fantasy elements—man-eating giants, spells and counterspells, enchantresses who turned men into swine—that were probably recognized as fantasy elements and responded to as such by at least the more sophisticated members of his audience. By the end of the eighteenth century, something recognizably akin to modern literary fantasy was beginning to precipitate out from the millennia-old body of oral tradition—folk tales, fairy tales, mythology, songs and ballads, wonder tales, travelers’ tales, rural traditions about the Good Folk and haunted standing stones and the giants who slept under the countryside—first in the form of Gothic stories, ghost stories, and Arabesques, and later, by the middle of the next century, in a more self-conscious literary form in the work of writers such as William Morris and George MacDonald, who reworked the subject matter of the oral traditions to create new fantasy worlds for an audience sophisticated enough to respond to the fantasy elements as literary tropes rather than as fearfully regarded, half-remembered elements of folk beliefs—people who were more likely to be entertained by the idea of putting a saucer of milk out for the fairies than to actually do such a thing.

By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most respectable literary figures—Dickens, Twain, Poe, Kipling, Doyle, Saki, Chesterton, Wells—had written fantasy in one form or another, if only ghost stories or Gothic stories, and a few, like Thorne Smith, James Branch Cabell, and Lord Dunsany, had even made something of a specialty of it. But as World War II loomed ever closer over the horizon, fantasy somehow began to fall into disrepute, increasingly being considered as unhip, “anti-modern,” non-progressive, socially irresponsible, even déclassé. By the sterile and unsmiling fifties, very little fantasy was being published in any form, and, in the United States at least, fantasy as a genre, as a separate publishing category, did not exist.

When the last Ice Age started, and the glaciers ground down from the north to cover most of the North American continent, thousands of species of plants and trees, as well as the insects, birds, and animals associated with them, retreated to “cove forests” in the south, in what would eventually come to be called the Great Smoky Mountains; in those cove forests, they waited out the long domain of the ice, eventually moving north again to recolonize the land as the climate warmed and the glaciers retreated. Similarly, the lowly genre fantasy and science fiction magazines—Weird Tales and Unknown in the thirties and forties, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Fantastic, and the British Science Fantasy in the fifties and sixties—were the cove forests that sheltered fantasy during its long retreat from the glaciers of social realism, giving it a refuge in which to endure until the climate warmed enough to allow it to spread and repopulate again.

By the midsixties, largely through the efforts of pioneers such as Don Wollheim, Ian and Betty Ballantine, Don Benson, and Cele Goldsmith, fantasy had begun tentatively to emerge from the cove forests. And after the immense success of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy, the first American publishing line devoted to fantasy, the Ballantine Adult Fantasy line, was established. It would be followed by others in the decades to come, until by the current day fantasy is a huge, diverse, and commercially successful genre, one which has diversified into many different types: sword & sorcery, epic fantasy, high fantasy, comic fantasy, historical fantasy, alternate world fantasy, and others.

For the last few decades, the most common public image of the magic-user has almost certainly been that of the benign, white-bearded, slouch-hatted, staff-wielding wizard—an image primarily composed of a large measure of Tolkien’s Gandalf the Grey and J. K. Rowling’s Dumbledore, with perhaps a jigger of T. H. White’s Merlin thrown in for flavor. Throughout history, though, the magic-user has worn many faces, sometimes benevolent and wise, sometimes evil and malign—sometimes, ambiguously, both. To the ancient Greeks, magic was the Great Science. The famous mystic Agrippa considered magic to be the true path of communion with God. Conversely, to medieval European society, the magic-user was one who collaborated with the Devil in the spreading of evil throughout the world, in the corruption and ruination of Christian souls—and the smoke of hundreds of burning witches and warlocks filled the chilly autumn air for a hundred years or more. To some Amerind tribes, the magic-user was either malevolent or benign, depending on the use to which their magic was put. In fact, nearly every human society has its own version of the magic-user. In Mexico, the sorcerer is curandero, brujo, or bruja. In Haiti, they are houngan or quimboiseur; in Amerind lore, the Shaman or Singer; in Jewish mysticism, the kabbalist; in Gypsy circles, the chóvihánni, the witch; in parts of today’s rural America, the hoodoo or conjure man or root woman; to the Maori of New Zealand, the tohunga makutu … and so on, throughout the world, in the most “progressive” societies no less than the most “primitive.”

The fact is, we’re all still sorcerers under the skin, and magic seems to be part of the intuitive cultural heritage of most human beings. Whenever you cross your fingers to ward off bad luck, or knock on wood, or refuse to change your lucky underwear before the big game, or ensure the health of your mother’s back by not stepping on the cracks in the sidewalk—or, for that matter, when you deliberately step on them, with malice aforethought—then you are putting on the mantle of the sorcerer, attempting to affect the world through magic. Then you are practicing magic, as surely as the medieval alchemist puttering with his alembics and pestles, as surely as the bear-masked, stag-horned Cro-Magnon shaman making ritual magic in the darkness of the deep caves at Rouffignac.

In this anthology, I’ve endeavored to cover the whole world of magic. Here you will find benevolent white wizards and the blackest of black magicians. Here you’ll visit the troll-haunted hills of eighteenth-century Iceland … Victorian Ireland, where the hosts of the Sidhe are gathering for war … the remote wilderness regions of Appalachia and the hill-country of Kentucky, where ancient ghosts still roam … and the streets of modern-day New York City and Los Angeles, where dangerous magic lurks around every corner. Then you’ll visit worlds of the imagination outside the time and space we know … touring the fabled, enchanted metropolis of Calfia; the bleak marshes and crumbling towns of the Mesoge, where the dead come back to prey on the living; the grim city of Uzur-Kalden, at the very edge of the world, where doomed adventures gather to set forth on quests from which few if any of them will return … visit The Land of the Falling Wall in the last days of a dying Earth to drink and dine at the Tarn House (famous for its Hissing Eels!); shop at the Mother of Markets in Messaline for bizarre simulacrum in company with Bijou the Artificer; attend the 119th Grand Symposium, presided over by the High Magnus himself, to watch a contest of skills between the world’s greatest magicians; join a perilous quest for cold mages vital to the prestige of the Great Houses who rule an alternate version of Rome after the Empire’s fall … enter an Elf-Hill, from which it may be impossible to escape … ride in the Devil’s Terraplane, join a village wizard in a seemingly hopeless battle to stand against the most malign of magics … try to talk a comet out of destroying the world … fight Revenants with fiery eyes, a toy-eater, a sinister ensorceled book … meet Dr. Dee, the famous Victorian scholar and magician … Masquelayne the Incomparable, the Eyeless One, the Lord of the Black Tor, Molloqos the Melancholy … Djinn, trolls, elves, osteomancers, egregores, deodands, grues, erbs, ghouls, scorpion-tailed manticores … the Lords of the Sidhe; the guardian spirits of Iceland; saints and sinners; the singing heads on stakes known as the Kallistochoi, who maintain magic with their endless song; Archangel Bob; the Holy Whore of Heaven; a Bouncing Boy Terror; and the Devil’s Son-in-Law.

Such dreams are inspired by magic—in fact, you could make an argument that they are magic. Such dreams persist, and cross the gulf of generations and even the awful gulf of the grave; cross all barriers of race or age or class or sex or nationality; transcend time itself. Here are dreams that, it is my fervent hope, will still be touching other people’s minds and hearts and stirring them in their turn to dream long after everyone in this anthology or associated with it have gone to dust.