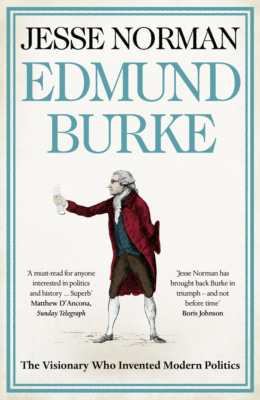

Read the book: «Edmund Burke: The Visionary Who Invented Modern Politics»

EDMUND BURKE

The Visionary Who Invented Modern Politics

JESSE NORMAN

Contents

Cover

Title Page

List of Illustrations

Introduction

PART ONE: LIFE

1. An Irishman Abroad, 1730–1759

2. In and Out of Power, 1759–1774

3. Ireland, America and King Mob, 1774–1780

4. India, Economical Reform and the King’s Madness, 1780–1789

5. Reflecting on Revolution, 1789–1797

PART TWO: THOUGHT

6. Reputation, Reason and the Enlightenment Project

7. The Social Self

8. Forging Modern Politics

9. The Rise of Liberal Individualism

10. The Recovery of Value

Conclusion: Burke Today

Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

List of Illustrations

1: Gin Lane, by William Hogarth, etching and engraving, published 1 February 1751 © The Trustees of the British Museum

2: Idol-Worship or the way to preferment, anonymous, etching, 1740 © The Trustees of the British Museum

3: A literary party at Sir Joshua Reynolds’s, by D. George Thompson, after James William Edmund Doyle, stipple and line engraving, published by Owen Bailey 1 October 1851 © National Portrait Gallery, London

4: The House of Commons 1793–94, by Karl Anton Hickel, oil on canvas, 1793–1795 © National Portrait Gallery, London

5: Portrait of Charles Watson-Wentworth, 2nd Marquess of Rockingham, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, oil on canvas, feigned oval, circa 1768 © National Portrait Gallery, London

6: Portrait of John Wilkes, by James Watson, after Robert Edge Pine, mezzotint, published 1764 © National Portrait Gallery, London

7: Portrait of Charles James Fox, by Karl Anton Hickel, oil on canvas, 1794 © National Portrait Gallery, London

8: Portrait of Edmund Burke, studio of Sir Joshua Reynolds, oil on canvas, circa 1769 or later © National Portrait Gallery, London

9: Map of India in the time of Clive, in Charles Colbeck (ed.), The Public Schools Historical Atlas, Longmans, Green & Co. (London, 1905)

10: Concerto coalitionale, by James Sayers, etching, published by Thomas Cornell 7 June 1785 © National Portrait Gallery, London

11: The political-banditti assailing the saviour of India, by James Gillray, published by William Holland, hand-coloured etching, published by William Holland 11 May 1786 © The Trustees of the British Museum

12: Portrait of Warren Hastings, by John Henry Robinson, after Lemuel Francis Abbott, engraving, 1832 © Getty Images

13: A View of the Tryal of Warren Hastings Esqr. before the Court of Peers, in Westminster Hall, by Robert Pollard (etching) and Francis Jukes (aquatint), after Edward Dayes, etching and aquatint, published by Robert Pollard 3 January 1789 © Getty Images

14: Smelling out a Rat, by James Gillray, hand-coloured etching, published by Hannah Humphrey 3 December 1790 © The Trustees of the British Museum

15: Portrait of Richard Burke, by James Ward, after Sir Joshua Reynolds, mezzotint, published by James Ward 5 July 1800 © National Portrait Gallery, London

16: Thoughts on a Regicide Peace, by James Sayers, etching, published by Hannah Humphrey 14 October 1796 © National Portrait Gallery, London

17: Promis’d Horrors of the French Invasion, by James Gillray, hand-coloured etching and aquatint, published by Hannah Humphrey 20 October 1796 © National Portrait Gallery, London

18: Portrait of Edmund Burke, by James Barry, oil on canvas, circa 1771, reproduced by kind permission from the Board of Trinity College Dublin, Ireland

Introduction

EDMUND BURKE IS BOTH the greatest and the most underrated political thinker of the past 300 years. Born in 1730, he came from an extraordinary period in British history, the age of Samuel Johnson, Adam Smith, Edward Gibbon, David Garrick, Joshua Reynolds and David Hume, all of whom were his friends.

Burke was a philosopher-statesman of the first rank, a lifelong campaigner against arbitrary power and injustice, and a fierce champion of fundamental rights and the Anglo-American constitutional tradition. Endlessly lampooned in this, the golden age of caricature, he is nevertheless a figure for the ages. Some understood his greatness at the time: Dr Johnson once remarked that he did not begrudge Burke’s being the first man in the House of Commons, for he would be the first man everywhere.

Burke has been all but ignored in recent years, or reduced to a clutch of standard clichés and soundbites. Yet we cannot understand the defects of the modern world today, or modern politics, without him. He is the first great theorist of political parties and representative government, and the first great modern theorist of totalitarian thought. More widely, he offers a compelling critique of what has become known as liberal individualism, and the idea that human well-being is just a matter of satisfying individual wants. To this he joins a perspective with profound implications for many issues now facing policymakers across the globe, including the rise of religious extremism and terror, the atomization of society and loss of social cohesion, the emergence of the corporate state, challenges to the international rule of law, and the nature of revolution itself.

Over his long career Burke fought five great political battles: for more equal treatment of Catholics in Ireland; against British oppression of the thirteen American colonies; for constitutional restraints on executive power and royal patronage; against the corporate power of the East India Company in India; and most famously, against the influence and dogma of the French revolution. Their common theme – the inspiration for what W. B. Yeats described in his poem ‘The Seven Sages’ as Burke’s Great Melody – is his detestation of injustice and the abuse of power.

In these battles his record of practical achievement was mixed. He often overreached himself, he rarely exercised real political power, and he was variously denounced as vainglorious, a blowhard and an irrelevance. His private life was blighted by debt, which he was unwilling to relieve by the means of self-enrichment usual for the time. He offended King George III by his severe criticisms of royal influence, and by his support for a regency during the King’s period of madness. A man of enormous personal warmth and good humour, he lost friends and supporters by his near-obsessive insistence on the campaigns of the moment.

Yet in intellectual terms the extraordinary fact is not that Burke was occasionally wrong, but that he was so often right. Not only that, he was right for the right reasons – not through luck but because his powers of analysis, imagination and empathy gave him an extraordinary gift of prophecy. Thus he anticipated many of the effects of British rule in Ireland; the loss of the American colonies; the overreach of the East India Company; and the disastrous consequences of revolution in France. Modern conceptions of social capital and human well-being have their proper place within his thought, and his vision of community, free institutions and civic virtue still has profound and unrecognized implications for politicians today. Lord Randolph Churchill, father of Winston, once summarized Disraeli’s life as ‘Failure, failure, failure, partial success, renewed failure, ultimate and complete triumph.’ The same might be said of Edmund Burke.

There are many reasons for the recent neglect of Burke. He is not an executive politician, like a Pitt or a Peel, and his story is more one of intellect and imagination than of political achievement. His thought is multifarious and scattered across a vast array of pamphlets, speeches and letters, from which it must be quarried by the patient scholar. He is a master of English prose but remains somewhat alienated from current literary or academic debates, in part because he was a working politician, and so perhaps a victim of the distaste that politics often inspires. And he deliberately withholds himself: as he wrote at the age of sixteen to his best friend Richard Shackleton, ‘We live in a world in which everyone is on the catch, and the only way to be safe is to be silent, silent in any affair of consequence, and I think it would not be a bad rule for every man to keep within what he thinks of others, of himself, and of his own affairs.’ Burke’s speeches, his writings and even his letters are notably short on confidences, gossip or personal colour. This is far removed from the modern confessional style.

Moreover, although few more quotable writers have ever existed, Burke himself and his ideas resist brief summary. Even sympathetic readers have seen him as an enigma or a contradiction. They have struggled to understand how he could be both a supporter of the American colonists and a critic of the French revolution; how he could staunchly argue for the established order, yet defend dissenters and Catholics and alienate the Crown; how he could both dismiss abstract rights and insist upon the importance of rights within the rule of law.

For their part, his many critics have accused him of incoherence, hypocrisy, even madness. In particular, for Thomas Paine, and then Karl Marx, Burke is a placeman, a paid propagandist and an apologist for aristocracy and privilege. Such claims were echoed in the twentieth century by the influential historian Lewis Namier and his followers, who generally took a narrow and cynical view of Burke’s achievements as a thinker and statesman. Even today, it is striking how much the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, for example, owes intellectually to Burke, even while he belittles Burke’s ideas. Those who attend to Burke’s life often detect inconsistency, because they ignore the deeper consistency of his thought.

But on the other side of the argument such has been Burke’s status, especially among conservatives, that his life has regularly been co-opted for political purposes. In the 1830s Disraeli claimed to identify a Tory line of succession including Burke and culminating by implication in himself, only to exclude Burke (and Peel) after he was refused office by Peel in 1841. In the USA, Presidents Woodrow Wilson and Theodore Roosevelt were happy to count Burke their ally, as did a generation of anti-communists during the Cold War and again after the fall of the Iron Curtain. And at a far less exalted level, one way to read the present book is as a modern Appeal from the Old to the New Whigs (sic).

Burke has been well served by his biographers over the years, including James Prior and John Morley in the nineteenth century; Philip Magnus, Carl Cone, Russell Kirk, Stanley Ayling and Conor Cruise O’Brien in the twentieth; and most recently F. P. Lock. To them the present volume owes an enormous debt of gratitude, and to Lock’s authoritative two-volume study of 1998–2006 in particular. The same is true of the work of many scholars listed in the Acknowledgements, Notes and Bibliography.

This book is not a work of primary research, though it incorporates some important recent discoveries. Rather, it is a personal interpretation of Burke’s life and thought, which draws heavily on my own background in philosophy and experience as a working politician. It seeks not merely to present Edmund Burke as a man, and to trace his life against the astonishingly rich tapestry of eighteenth-century society, but to make the case for him as a statesman and thinker. It is short and inevitably selective, and this risks underplaying both conflict and development in Burke’s ideas; but its argument is for a deeper coherence. Somewhat unusually, the book is structured in two parts, Life and Thought, so that the interested reader can enjoy his life for its own sake, and engage with Burke’s thought with the wider context of his life and society already in hand. My hope is to start to do for Edmund Burke what others have done for Adam Smith over the past thirty years: to recognize him publicly as one of the seminal thinkers of the present age.

The political theorist Harold Laski once said of Burke:

He brought to the political philosophy of his generation a sense of its direction, a lofty vigour of purpose, and a full knowledge of its complexity, such as no other statesman has ever possessed. His flashes of insight are things that go, as few men have ever gone, into the hidden deeps of political complexity … He wrote what constitutes the supreme analysis of the statesman’s art.

The purpose of this book is to explain how he came to write it, why it is, and why he and it matter today.

PART ONE

ONE

An Irishman Abroad, 1730–1759

IN THE YEAR 1729 THERE appeared in the city of Dublin a rather curious publication, by an anonymous author. It did not have the snappiest of titles: A Modest Proposal for Preventing the Children of Poor People in Ireland from Being a Burden to Their Parents or Country, and for Making Them Beneficial to the Public. But, its title apart, in many ways A Modest Proposal was the prototype of the modern policy pamphlet, of a type familiar from present-day think tanks the world over.

The pamphlet proceeded in the most measured language from diagnosis to statistical analysis to policy recommendation. Ireland was then subject to very serious poverty and malnutrition, the author noted. Careful calculation revealed that the number of new births far exceeded the level required to replenish the population. No work existed in handcrafts or agriculture for the mothers, with the result that the traveller to Dublin found:

the streets, the roads, and cabin doors crowded with beggars of the female sex, followed by three, four, or six children, all in rags and importuning every passenger for an alms. These mothers, instead of being able to work for their honest livelihood, are forced to employ all their time in strolling to beg sustenance for their helpless infants: who as they grow up either turn thieves for want of work, or leave their dear native country.

But, the author said, there was a ready-made solution, then as often now imported from America: ‘I have been assured by a very knowing American of my acquaintance in London, that a young healthy child well nursed is at a year old a most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food, whether stewed, roasted, baked, or boiled; and I make no doubt that it will equally serve in a fricassee or a ragout.’ Not only were one-year-old children good food; they had other uses as well: ‘Those who are more thrifty (as I must confess the times require) may flay the carcass; the skin of which artificially dressed will make admirable gloves for ladies, and summer boots for fine gentlemen.’

Jonathan Swift’s pamphlet is one of the most brilliant sustained satires in the English language, a masterpiece of moral indignation which effortlessly ridiculed targets ranging from the new vogue for statistics to contemporary attitudes towards the poor. But the economic and social facts he described have never been questioned.

This was, precisely, the Ireland into which Edmund Burke was born, on Arran Quay by the River Liffey in Dublin, on New Year’s Day 1730. Dublin then was a place of extremes, in which enormous wealth coexisted with desperate poverty and, frequently, starvation. Nor were these evils confined to the city. In an essay of 1748, Burke and some friends indignantly described the condition of the rural poor at that time: ‘Money is a stranger to them … as for their food, it is notorious they seldom taste bread or meat; their diet, in summer, is potatoes and sour milk; in winter … they are still worse, living on the same root, made palatable by a little salt, and accompanied by water.’ As for what they wore: ‘their clothes so ragged … nay, it is no uncommon sight to see half a dozen children run quite naked out of a cabin, scarcely distinguishable from a dunghill.’

Fortunately the Burkes themselves lived somewhat more comfortably. Edmund was the third of four surviving children, a sometimes neglected position in a family. It may have been so here, for his brothers Garrett and Richard were eldest and youngest, while his elder sister Juliana was the only girl. The Burkes were likely of Anglo-Norman ‘Old English’ extraction, originally Catholic and not part of the New English ascendancy which took control of Ireland in the seventeenth century. Edmund’s father Richard, probably born in County Cork in the south-west, had long since left the land for the city. He was an attorney, a Protestant and a self-made man who had risen in the law through hard work, described by Edmund’s friend Richard Shackleton as ‘of middling circumstances, fretful temper and punctual honesty’. His wife Mary Nagle was also from County Cork. But otherwise she could hardly have been more different: a Catholic countrywoman from a genteel but much reduced family of landowners. The Nagles were not merely Catholics but Jacobites, who had supported the claims to the throne of James II and his successors after the revolution of 1688, which brought the Protestant William of Orange to the throne as William III. Forty years later most of their land, and much of their dignity, had gone.

By the 1720s Ireland was in name a country, indeed a kingdom, but in reality an English dominion. The functions of state were controlled by Protestants, generally Englishmen, and directed from London. Access to education and opportunities for advancement were similarly restricted. Catholics were barred from the professions, from jury service and from exercising the vote. A host of other laws oppressed them, from owning firearms to controls on inheritance and land ownership. Much of their land had been taken over by Protestant nobility and gentry, who were not offset in influence by a class of yeoman farmers as in England. The result was huge inequalities of wealth and well-being, compounding and in turn compounded by religious hatred and political instability.

Some have suggested that Richard Burke himself was an apostate, one of many who converted in order to get on. But whether or not it was Richard or one of his forebears who converted, it is evident that Edmund grew up as the product of a marriage mixed not merely by religion but by trajectory and class. He and his brothers Garrett and Richard were raised as Protestants, Juliana as a Catholic. Protestantism, the city and social aspiration, it seemed, belonged to the future; Catholicism and rural life to the past. Loyalties must, then, be divided. This may be one reason why Burke was to develop such an extraordinary moral imagination, able to reach out at once in all directions, to comprehend aristocrat and revolutionary, Catholic and Protestant, underclass and hierarchy alike.

Home life was not easy, for Richard Burke appears to have been a man of rigid and unyielding disposition. The will he left at his death is a mass of small-minded bequests and instructions, almost designed to split the estate and set family members against each other. He also had a foul temper. ‘My dear friend Burke leads a very unhappy life from his father’s temper,’ Richard Shackleton reported in 1747. ‘… He must not stir out at night by any means, and if he stays at home there is some new subject for abuse.’

Luckily, here too Mary Burke was quite different from her husband. Little is known about her. But, as scholars have noted, Burke’s references to his mother are always warm and affectionate, to his father never so. In adult life Burke notably combined high principle and personal probity with an open, trusting and generous disposition towards others, though he also knew how to bear a grudge. Without diving too deep into psychological speculation, it is not hard to see his father on the one side, his mother on the other. As a child Burke spent some time recuperating from illness with his Nagle cousins in the Blackwater Valley in County Cork, and studied at a rural ‘hedge school’ in Ballyduff. The Valley was beautiful country, which made a profound impression on him; it may also have laid the foundations for his understanding of Gaelic culture, and his lifelong sympathy with the plight of the Irish Catholics under the penal laws.

In May 1741 Edmund, then aged eleven, Garrett (fifteen) and Richard (seven) were sent away to school. Juliana (thirteen) was kept at home with her parents. Edmund had left Dublin previously, to stay with his mother’s family in County Cork and get away from the damp and disease of the city. Now he went for an education. His destination was a small non-denominational boarding school in the village of Ballitore, about thirty miles south-west of Dublin. It was run by Abraham Shackleton, a Quaker and the father of Richard Shackleton, who was to become Burke’s greatest early friend.

Abraham Shackleton was a remarkable man, who had taught himself Latin at the age of twenty in order to become a schoolmaster. The curriculum was a traditional one, with a strong emphasis on classical languages and literature, and work was taken seriously. Yet it is clear that Burke quickly settled in, and that Shackleton’s influence was a sympathetic one, as much moral as intellectual. In 1757, when Burke had moved to London and was building an early reputation as a writer, he thanked his former schoolmaster, saying ‘I received the education, that, if I am anything, has made me so.’ Still more strikingly, in a poem on Ballitore, Burke paid generous tribute to the older man: ‘Whose breast all virtues long have made their home / where Courtesy’s stream doth without flattery flow / and the just use of Wealth without the show’. The warmth of these words vividly contrasts with the extant references to Burke’s own father, and there is perhaps even a touch of reproof to his father’s temper in the second line.

As a non-denominational school run by Quakers, Ballitore was itself a minor study in contrasts. Its influence on Burke was profound. Not in point of doctrine: the Quakers were dissenters, pacifists and abstainers from alcohol, which Burke never was. But he evidently appreciated the plainspokenness and straight dealing he experienced. The egalitarian ethos of the Quakers may also have left its mark with him in later life: in his support for the underdog, in his lifelong willingness to engage intellectually with others, in his hatred of arbitrary power, in his belief that the social order should benefit all. The mature Burke admired the Quakers’ commitment to good and active citizenship. While he did not share their opposition to religious hierarchy and priesthood, his arguments for the established Church were notably based more on institutional authority than on revelation to the elect. When Burke came to consider the American revolution in the 1770s, its values and history were things to which he was already instinctively sympathetic.

In 1744 Burke left Ballitore for Trinity College Dublin. Trinity College was then the only institution of higher learning in Ireland, an avowedly Protestant establishment founded by Elizabeth I in 1592 to train clergy for the Church of Ireland. It was smaller than even the smallest universities today, with between 300 and 500 students, more of them headed into the Church than any other profession. The curriculum, based on the medieval trivium and quadrivium, was divided into ‘humanity’ (Latin and Greek texts) and ‘science’ (including mathematics, astronomy, geography and physics, and finally metaphysics and ethics). There were no facilities for social activities or sports within the college.

The average age at entry was sixteen, so that when Burke entered at age fourteen he was among the youngest students in the college. Academically, he performed well but not consistently so. Awarded a scholarship in 1746 after two days of examination on Greek and Latin authors, he was nevertheless ranked only in the top half of the class overall. For assiduity and diligence, he was ranked in the bottom quarter. The reason why is fairly evident: Burke was not happy either at home or at college. Going to Trinity meant, first of all, leaving the Shackletons and returning to the family home, to foul city air and his father’s angry moods. In the classroom, he was younger than his fellows, and obviously bored by the often laborious and pedantic teaching. Matters were made worse by his reliance on his father for financial support, support tied to a legal career which held few attractions for him. Many people make the greatest friendships of their lives at university; of the forty or so of Burke’s contemporaries who we know studied with him for four years, it seems that none became a good friend while there.

Burke found his outlets elsewhere, in vast amounts of reading, in friendships outside the classroom, and in writing. His sixty surviving undergraduate letters, all to Richard Shackleton, attest to the breadth of his social and literary interests, as well as to his habit of spending three hours a day in the public library. Burke at this time had been seized by what he called a poetical madness or furor poeticus. He wanted to become a poet, and seems to have made his literary debut with a satirical poem, probably published in 1747. But he was an omnivorous autodidact, and he used his letters to experiment with new ideas and topics and literary forms, as well as in-jokes, banter and self-analysis, with Richard as a private and supportive audience.

This instinct for self-improvement also led Burke to play a part in setting up two societies at Trinity. Each combined drinking and conviviality with a serious purpose. The first had four members, and focused on the writing of burlesques or parodies, a very popular genre of the time; the second, named absurdly the Academy of Belles Lettres, had seven members and focused on rhetoric and debate. Neither lasted more than a few months. Both evinced Burke’s lifelong clubbability, as well as a restless ambition to spread his wings.

Altogether more serious was the Reformer. This was a periodical, which ran weekly for thirteen issues in early 1748. Produced by a circle of friends including Burke, it combined essays on diverse topics with articles about the theatre – and in particular the rather controversial local Smock Alley Theatre, which was run by Thomas Sheridan, father of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, the playwright and Burke’s later parliamentary colleague and rival. The essays are unsigned except for the teasing initials B, S, U and Æ. But two contributions by Æ are sometimes thought to possess the stamp of the young Burke. One is devoted to the idea of public spirit, and includes a call for more generous patronage of poetry. The second is a vigorous analysis of rural poverty, which highlights and criticizes the extreme inequality of the age, and insists that the landowning aristocracy must discharge the responsibilities that come with property. These were, and would remain, characteristically Burkean themes.

Burke graduated from Trinity in February 1748. After that we know little of his activities for two years or so. Still under intense pressure to pursue a legal career, he may very well have worked in his father’s office, which will have done nothing to relieve his spirits. He may also have been sucked into local politics, and in particular into a fierce controversy stirred up by Charles Lucas, a radical who stood unsuccessfully in a highly contentious by-election to the Irish House of Commons. But we simply do not know for sure.

What we do know is that Burke went to London in 1750, aged twenty; and that for him, as for Samuel Johnson and so many others, this was a crucial turning point. Ireland was his birthplace. One way or another, Ireland would always be in his thoughts. But Burke had never felt the joy of a settled life there: not with his family, not at school in Ballitore, not at Trinity. He never lost his Irish accent. But he returned to Ireland only three times over the next forty-seven years. London, and England, marked a new beginning.

The London that Burke encountered was by far the largest city in the British Isles. Its population of more than 600,000 people in 1750 was roughly one-tenth that of England as a whole, and ten times that of the next-largest city, Bristol. It was a place of squalor and stench, with huge overcrowding and only the most rudimentary sanitation. Pigs and fowl often lived in urban cellars. Diseases such as smallpox, typhoid fever and dysentery were rampant, with periodic outbreaks of influenza. The results were death and deformity, which hit the urban poor the hardest but left no family untouched. Barely one child in three survived childhood.

By way of antidote, people turned to gambling, cockfighting and the like, and above all to drinking gin. The latter, mixed with fruit cordials, was embraced on such an epic scale that the average annual consumption across the whole of England in 1743 was well over two gallons a head. When Burke arrived in London memories were still fresh of the notorious Judith Defour and, thanks to William Hogarth’s print Gin Lane (see following page/s), would remain so. It was she who in 1734 had strangled her own two-year-old daughter and sold the new petticoat the girl had been given at the parish workhouse in order to pay for gin. Five Acts of Parliament were required to bring the craze under control.