This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

Read the book: «The Debutante»

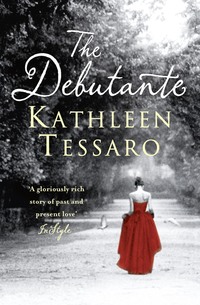

The

Debutante

Kathleen Tessaro

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2010

Copyright © Kathleen Tessaro 2010

Kathleen Tessaro asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007215393

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2010 ISBN: 9780007366019

Version: 2019-05-24

Note to Readers

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

[Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN xxxxxxxxxxxxx]*

[Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN: xxxxxxxxxxxxx, xx Edition]*

For Annabel

There is a dangerous silence in that hour A stillness, which leaves room for the full soul To open all itself, without the power Of calling wholly back its self-control: The silver light which, hallowing tree and tower, Sheds beauty and deep softness o’er the whole, Breathes also to the heart, and o’er it throws A loving languor, which is not repose.

LORD BYRON, Don Juan

Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Copyright

Note to Readers

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One

In the heart of the City of London

Part Two

5 St James’s Square

5 St James’s Square (continue)

Part Three

Endsleigh Devon

Read an extract of The Perfume Collector by Kathleen Tessaro

Keep Reading – The Perfume Collector

Keep Reading – Rare Objects

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

Also by Kathleen Tessaro

About the Publisher

Part One

In the heart of the City of London, tucked into one of the winding streets behind Gray’s Inn Square and Holborn Station, there’s a narrow passage known as Jockey’s Fields. It’s a meandering, uneven thread of a street that’s been there, largely unchanged, since the Great Fire. Regency carriages gave way to Victorian hackney cabs and now courier bikes speed down its sloping, cobbled way, diving between pedestrians.

It was early May; unseasonably hot – only nine in the morning and already seventy-six degrees. A cloudless blue sky set off the white dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in the distance. The pavement swelled with armies of workers, streaming from the nearby Tube station; girls in sorbet-coloured summer dresses, men in shirtsleeves, jackets over their arms, carrying strong coffee and newspapers, the rhythm of their heels a constant tattoo on the pavement.

Number 13 Jockey’s Fields was a lopsided, double-fronted Georgian building, painted black many years previously, and in need of a fresh coat, sandwiched between a betting office and a law practice. The door of Deveraux and Diplock, Valuers and Auctioneers of Quality, was propped open by a Chinese ebony figure of a small pug dog, most likely eighteenth century but in very bad repair, in the hopes of encouraging a gust of fresh morning air into the premises. Golden shafts of sunlight filtered in through the leaded glass windows, dust floating, suspended in its beams, settling in thick layers on the once illustrious, now slightly shabby interior of one of London’s lesser known auction houses. The oriental carpet, a fine specimen of the silk hand-knotted variety of Northern Pakistan during the last century, was threadbare. The delft china planters which graced the mantelpiece, brimming with richly scented white hyacinth, were just that bit too chipped to be sold at any real profit; and the seats of the 1930s leather club chairs by the fireplace sagged almost to the floor, their springs poking through the horse-hair backing. Reproduction Canalettos hung next to the

better watercolour dabblings of long-dead country-house hostesses; studies of landscapes, flowers and fond attempts at children’s portraits. For Deveraux and Diplock was the natural choice of those once aristocratic families whose fortunes had lost pace with their breeding and who wished to have their heirlooms sold quickly and discreetly, rather than in the very public catalogues of Sotheby’s and Christie’s. They were known by word of mouth and reputation, having traded with the same European and American antique dealers for decades. Theirs was a dying art for a dying class; a kind of undertakers for antiquities, presided over by Rachel Deveraux, whose late husband Paul had inherited the business when they were first married thirty-six years ago.

Rachel, smoking a cigarette in a long, mother-of-pearl holder which she’d acquired clearing the estate of an impoverished 1920s film star, sat contemplating the mountain of paperwork on her huge, roll-top desk. At sixty-seven, she was still striking, with large brown eyes and a knowing, disarming smile. Her style was unorthodox; flowing layers of modern, asymmetrical Japanese-inspired tailoring. And she had a weakness for red shoes that had become a personal trademark over the years – today’s pair were vintage Ferragamo pumps circa 1989. Pushing her thick silver hair away from her face, she looked up at the tall, well-dressed man prowling the floor in front of her.

‘It will be fun, Jack.’ She exhaled; a long, thin stream of smoke rising like a spectre, floating round her head.

‘Think of her as a companion, someone to talk to.’

‘I don’t need help. I’m perfectly capable of doing it on my own.’

Jack Coates gave the impression of youth even though he was nearing his mid-forties. Slender, with elegant aquiline features, thick lashes framing indigo eyes, he moved with an animal grace. His dark hair was closely cropped, his linen suit well-tailored and pressed; yet underneath his polished exterior a raw, unpredictable energy flowed. He was a man straining at his own definition of himself. Frowning, he stopped, fingers drumming the top of the filing cabinet.

‘I prefer to do it alone. There’s nothing more tedious than talking to strangers.’

‘It’s a three-hour drive.’ Rachel leaned back, watching him. ‘She’ll hardly be a stranger by the time you arrive.’

‘I’d rather go on my own,’ he said, again.

‘That’s the trouble with you; you rather do everything on your own. It’s not good for you. Besides –’ she flicked a bit of ash into an empty teacup – ‘she’s very pretty.’

He looked up.

She arched an eyebrow, the hint of a smile on her lips.

‘What difference does that make?’ Jamming his hands into pockets, he turned away. ‘Perhaps I should point out that this isn’t some small turn-of-the-century Russian village and you’re not an ageing Jewish matchmaker eking a living out by tossing complete strangers together and adding a ring. We’re in London, Rachel. The millennium dawns. And I’m perfectly capable of doing the job I’ve been doing for the past four years on my own – without the assistance of young nieces of yours, fresh from New York, trailing round after me.’

She tried a different tack.

‘She’s an artist. She’ll be very helpful. She has an excellent eye.’

He snorted.

‘She’s had a difficult time of it lately.’

‘Which what, roughly translates to “she’s broken up with her boyfriend”? Like I said, I don’t need a companion. And especially not some moody art student who’ll spend the entire time on the phone, arguing with her lover.’

Stubbing out her cigarette, Rachel took out her reading glasses. ‘I’ve already told her she can go.’

He swung round. ‘Rachel!’

‘It’s a large house, Jack. Even with two of you, it will take you days to value and catalogue the whole thing. And whether you deign to acknowledge it or not, you need help. You don’t have to talk to her at length or share the contents of your innermost heart. But if you can manage to be civil, you might just notice that it’s actually nicer not doing everything on your own.’

He paced like a caged animal. ‘I can’t believe you’ve done this!’

‘Done what?’ She looked at him hard over the top of her glasses. ‘Hired an assistant? I am your employer. Besides, she’s smart. She studied at the Courtauld, Chelsea, Camberwell –’

‘How many art colleges does a person need?’

‘Well,’ she grinned slyly, ‘she was very good at getting

into them.’

‘This isn’t helping.’

She laughed. ‘It will be an adventure!’

‘I don’t want an adventure.’

‘She’s different now.’

‘I work alone.’

‘Well –’ she rifled through the stacks of invoices and receipts, searching for something – ‘now you have an assistant to help you.’

‘This is nepotism, pure and simple!’

She looked up. ‘Nothing about Katie is pure or simple. The sooner you understand that, the easier it will be.’

‘What did she do in New York anyway?’

‘I’m not sure.’

‘I thought you two were close.’

‘Her father had just died. He was young; an alcoholic. She wanted a new start and we had some connections there; Paul knew one or two dealers who might be willing to help her find her feet. Tim Bolles, Derek Constantine –’

‘Constantine?’ Jack stopped. ‘I thought he only catered for the super-rich.’

‘Yes, well. He took a shine to her.’

‘I’ll bet he did!’

She gave him a look. ‘I don’t believe he’s that way inclined.’

‘I’m sure he inclines himself to whoever’s got the cash, which doesn’t exactly add to his charms.’

‘New York is not a city a young woman can just waltz into. You need contacts.’ Opening the top drawer, she sifted through its contents. ‘I’m just guessing, but I take it you don’t like him.’

‘My father had dealings with him. Years ago. So –’ he changed the subject – ‘she’s staying with you, is she?’

‘For the time being. Her mother lives in Spain.’ She sighed; her face tensed. ‘She’s so different. So entirely, completely different. I’d heard nothing for months…not even a phone call…and then out of blue, there she was.’

Suddenly a courier bike, buzzing like a giant wasp, tore past the doorway at breakneck speed.

‘Good God!’ Jack turned, tracking it as it narrowly avoided a couple of girls, coming out of a coffee shop. ‘They’re a menace! One of these days someone’s going to get hurt!’

‘Jack.’ Rachel pressed her hand over his and gave him her most winning smile. ‘Do this for me, please? I think it will be good for her; a trip to the country, time with someone closer to her own age.’

‘Ha!’ He squeezed her fingers lightly before moving his hand away. ‘I’m not a babysitter, Rachel. Where is this house anyway?’

‘On the coast in Devon. Endsleigh. Have you ever heard of it?’

He shook his head. ‘Look, I’m not…you know, good with people.’

‘Maybe. But you’re a good man.’

‘I’m an awkward man,’ he corrected, wandering over to the fireplace.

‘You don’t need to worry. Katie won’t be a problem, I promise. You might even enjoy it.’ She caught his eye in the mirror hanging above the mantelpiece. Her voice softened. ‘You need to make an effort now.’

‘Yeah, that’s what they tell me.’

Rachel was quiet. A rare breeze rustled the papers in front of her.

‘Well. There we go,’ Jack concluded. He picked up his briefcase from where he’d left it, on the seat of one of the sagging leather chairs, and headed for the door. ‘I’ve got work to do.’

‘Jack…’

‘Tell your niece we leave at eight thirty tomorrow.’ He turned. ‘And I’m not wasting the whole morning waiting for her, so she’d better be ready. Oh –’ he paused on the threshold – ‘and we’ll be listening to Le Nozze di Figaro on the way down, so no conversation necessary.’

She laughed. ‘And if she doesn’t like opera?’

‘She doesn’t need to come!’ He waved, striding out, quickly lost in the stream of people on Jockey’s Fields.

Rachel pulled off her glasses, rubbed her eyes. They hurt today; not enough sleep.

Digging through her handbag, she pulled out her cigarettes.

This job wasn’t good for him. He needed to be somewhere he could be around people, back in the thick of life, not picking through the belongings of the dead. Perhaps she ought to hire a secretary. Some cheerful young woman to bring him out of himself. A redhead, perhaps?

Catching herself, she smiled. He was right; she wasn’t a Jewish matchmaker.

Swivelling round in her chair, she flicked through the piles of paper, looking again for the phone number. Her late husband always claimed her very distinctive filing system would fail her one day. Today was not the day though; she needed more than anything to talk to her sister Anna. Especially now that Katie was back. The role of matriarch was Anna’s forte. Rachel did Bohemia, Anna domesticity. That was the way it had always been. At least that was the way it had been until Anna’s recent decampment to a small town outside Malaga left Rachel feeling unexpectedly abandoned and strangely affronted. Her shock was purely selfish, she knew that. Her sister had dared to change the well-worn script of their roles without consulting her, tossing off her old life as if it were nothing more than a garment, grown shapeless and illfitting from too much use.

‘I’m tired of London,’ Anna had declared, as Rachel helped her pack up the flat she’d owned in Highgate for twenty-two years. ‘I want to start again, somewhere fresh, where nobody knows me.’

She’d had a child’s optimism that day; a purpose and energy Rachel hadn’t seen in her for years. And secretly she’d envied her courage and the audacity of her sureness. Anna’s life hadn’t been easy. The childhood sweetheart she’d married failed her, turning into a desperate, unreliable alcoholic. She’d struggled to raise Katie on her own, only to endure her silences and rebellion, followed by her sudden desertion to America. It was no wonder Anna decided to escape. And she deserved a new life in a country bathed in sun and warm Latin temperament. Still, when she’d rung last week, Rachel had been short with her; fractious. She’d scribbled her number down on some scrap, promising herself she’d transfer it to her address book later. Now it was later and she couldn’t find the damn thing.

Hold on. What was this?

She tugged at the corner of something jutting out beneath a pile of overdue VAT forms.

It was a postcard.

At first glance it appeared to be of Ingres’s famous painting Odalisque. But on closer examination the blue eyes of the reclining courtesan were painted pale green, the same clear celadon as Katie’s. One half of her face was bathed in shadow, the other in light. Her unnerving gaze managed nevertheless to be elusive; her very directness a mask behind which she remained hidden. Turning it over, there was a message scrawled across the back in Katie’s near-hieroglyphic hand.

‘Portrait of the artist’ xxK

Across the bottom it read, ‘The Real Fake: Original Reproductions by Cate Albion’.

Cate. She’d changed everything she could about herself

– her name, her hair colour, even her work. Reproductions of old masters were a far cry from the huge triptychs she produced in art school; full of rage and surprising power. But then again, part of her talent was always her ability to reinvent herself, ransacking wide-ranging styles and iconography with a ruthlessness and speed that was frightening.

Nothing was pure and simple about Katie. Even her career was layered with illusion and double entendre.

It wasn’t what she was looking for, yet Rachel slipped it thoughtfully into the large leather handbag at her feet.

The real fake.

As a child Katie was shy, introverted; looked like she was made of glass. But if there was something broken, something missing, she was invariably behind it. Or, later on, if there was a party when someone’s parents were out of town, it would turn out to have been Katie’s idea. The girl caught not only smoking behind the bicycle sheds at school, but selling the cigarettes too? Katie. There was fire, a certain streak of will that burned slowly, deeply, beneath the surface; flaring when challenged. It was surprising, perverse; often funny and ironic.

Rachel thought again of the lost young woman, wandering around her flat in Marylebone. So quiet, so unsure.

When she’d asked Katie what had brought her back to London, she’d simply shrugged her shoulders. ‘I need a break. Some perspective.’ Then she’d turned to Rachel, suddenly wide-eyed, tense. ‘You don’t mind, do you?’

‘No, no of course not.’ Rachel had assured her. ‘You must stay as long as you like.’

She’d dropped the subject after that. But the expression on Katie’s face haunted her.

Lighting another cigarette, Rachel cradled her chin in her hand, taking a deep drag.

It wasn’t like Katie to be frightened.

Secretive, yes. But never afraid.

Jack drove up in front of number 1a Upper Wimpole Street the next morning in his pride and joy, an old Triumph, circa 1963. There on the doorstep was a young woman, slight, slender; hair in a sleek bob, white blonde in the early-morning sun. Her face was oval, with green eyes; her skin a light golden tan. She was wearing a pale linen dress, sandals and a cream cashmere cardigan. In one hand she had an overnight case and in the other a vintage Hermès Kelly bag in bright orange. Silver bangles dangled from her delicate wrists, a simple, slightly pink strand of pearls round her neck.

She was beautiful.

It was disturbing how attractive she was.

This was not the struggling artist he was expecting. This was a socialite; a starlet; a creature of style, grace and poise. Walking down the steps, she moved with a slow undercurrent of sexual possibility. When she slid into the seat next to him, Jack was aware of the soft scent of freshcut grass, mint and a hint of tuberose; a heady mix full of sharp edges and refined luxury. It had been a long time since an attractive woman had sat next to him in his car. It was an unsettling, sensuous feeling.

Turning, she extended her hand. ‘I’m Cate.’

Her palm slipped into his; cool and smooth. He found himself not shaking it, but instead holding it, almost reverently, in his own. She smiled, lips parting slowly across a row of even white teeth, green eyes fixed on his. And before he knew it, he was smiling back, that slightly lopsided grin of his that creased his eyes and wrinkled his nose, at this golden creature whose hand fitted so nicely into the hollow of his own; who adorned so perfectly the front seat of his vintage convertible.

‘You don’t want to do this and neither do I.’ Her voice was low, intimate. ‘We needn’t make conversation.’

And with that, she withdrew her hand, knotting a silk scarf round her head; slipping on a pair of tortoiseshell sunglasses.

And she was gone, removed from him already.

He blinked. ‘Do you like…is opera all right? Le Nozze di Figaro?’

She nodded.

He pressed the play button, started the engine and pulled out into traffic. He’d been dreading the social strain of today so much that sleep was an impossibility. Earlier, while packing his bag, he’d cursed Rachel.

Now, as he drove into the wide avenue of Portland Place, the cool green of Regent’s Park spread before them, he was baffled, bemused. He’d anticipated a nervous self-absorbed girl; someone whose inane questions would have to be fended off. It was his intention to create an unspoken boundary between them with the briskness of his tone and the curtness of his replies. But now his mind raced, trying to devise some clever way of hearing the sound of her voice again.

Of course, he could always ask a simple question. But there was something delicious about sitting next to her in silence. Their intimacy was, after all, inevitable; hours, even days, stretched before them. He sensed that she knew this. And it intrigued him.

Keenly conscious of every movement of his body next to hers, he downshifted, his hand almost brushing against her knee. The furious zeal of the overture of Le Nozze di Figaro filled the air around them with exquisite, frenetic intensity. They sped round the arc of the Outer Circle of the park. The engine roared as he accelerated, ducking around a long line of traffic in an uncharacteristically daredevil move.

And suddenly she was laughing, head back, clutching her seat; an unexpectedly low, earthy chuckle.

She’s a woman who likes speed, he thought, childishly delighted with the success of his manoeuvre. And before he knew it, he was overtaking another three cars, zipping through a yellow light on the Marylebone Road and cutting off a lorry as they merged onto the motorway.

Horns blared behind them as they raced out of London.

And, for the first time in a long while, all was right with the world. It was a beautiful, sun-drenched morning – the entire summer spread out before them. He felt handsome, masculine and young.

And he was laughing too.

High on a cliff where the rolling countryside, dotted with cows and lambs, met the expanse of sea, Endsleigh stood alone. Part of an extensive farm, it commanded a view over the bay beneath and the surrounding hills that was breathtaking. Built in pale grey stone by a young, ambitious Robert Adam, it rose like a miniature Roman temple; its classical proportions blending harmoniously into the rich green fields that surrounded it, mirroring the Arcadian perfection of the landscape with its Palladian dome and restrained, slender columns. High stone walls extended for acres on either side of the house, protecting both the formal Italian rose gardens and the vegetable patches from the stormy winter winds, while the arched gravel drive and the central fountain, long out of use, lent the house an air of refined, easy symmetry.

It was impressive yet at the same time unruly, showing signs of recent neglect. The front lawns were overgrown; the fountain sprouted dry tufts of field grass, high enough almost to blot out the central figure of Artemis with her bow and arrow, balanced gracefully on one toe, midchase. There was no one to care if the guttering sagged or the roses grew wild. It was a house without a guardian; its beautiful exterior yielding, slowly, to the inevitable anarchy of nature and time.

Just before the drive, a discreet sign pointed the way to a campsite on the grounds, nearly a mile down the hill, closer to the shore and out of sight of the occupants in the main house. Below, the bay curved gently like an embracing arm, and beyond, the ocean melted into the sky, a pale grey strip blending into a vast canopy of blue. It was cloudless, bright. Cool gusts tempered the heat of the midday sun.

Jack pulled up, wheels crunching on the gravel of the drive, and turned off the engine.

They sat a moment, taking in the house, its position; the view of the countryside and the sea beyond. Neither of them wanted to move. Silence, thick and heavy, pressed in around them, tangible, like the heat. It was disorientating. The internal compass of every city dweller – the constant noise of distant lives humming away in the background – was missing.

‘It’s much bigger than I thought it would be,’ Cate said at last.

It was an odd observation. The beauty of the place was obvious, overwhelming. Could it be that she was calculating how long they would be alone here?

‘Yes. I suppose it is.’

Swinging the car door open, she climbed out. After so much time driving, the ground felt unsteady beneath her feet.

Jack followed and together they walked past the line of rose bushes, full-blown and fragrant, alive with the buzzing of insects, to the front door.

He pressed the bell. After a moment, footsteps drew closer.

A tall, thin man in a dark suit opened the heavy oak door. He was in his late fifties, with a long, sallow face and thinning, grey hair. He had large, mournful eyes, heavily ringed with dark circles.

‘You must be Mr Coates, from Deveraux and Diplock,’ he surmised, unsmiling.

‘Yes.’

‘Welcome.’ He shook Jack’s hand.

‘And this is Miss Albion, my…assistant,’ Jack added.

‘John Syms.’ The man introduced himself, inclining his head slightly in Cate’s direction, as if he’d only budgeted for one handshake and wasn’t going to be duped into another. ‘From the firm of Smith, Boothroy and Earl. We’re handling the liquidation of assets on behalf of the family.’ He stepped back, and they crossed the threshold into the entrance hall. ‘Welcome to Endsleigh.’

The hall was sparse and formal with black-and-white marble tiles and two enormous mahogany cabinets with fine inlay, both filled with collections of china. Over the fireplace hung a large, unremarkable oil painting of the house and grounds. Four great doors led off the hall into different quarters.

‘How was your journey?’ Mr Syms asked crisply.

‘Fine, thank you.’ Cate turned, examining the delicate Dresden china figurines arranged together in one of the cabinets. Their heads were leaning coyly towards one another, all translucent porcelain faces and pouting pink rosebud mouths, poised in picturesque tableaux of seduction and assignation.

‘Yes, traffic wasn’t too bad,’ Jack said, immediately wishing he’d thought of something less banal.

Mr Syms was a man of few words and even fewer social graces. ‘Splendid.’ Pleasantries dispensed with, he opened one of the doors. ‘Allow me to show you around.’

They followed him into the main hall with its sweeping galleried staircase, lined with family portraits and landscapes. It was a collection of country-house clichés – a pair of stiff black Gothic chairs stood on either side of an equally ancient oak table, stag’s heads and stuffed fish were mounted above the doorways; tucked under the stairwell there was even a bronze dinner gong.

Cate looked up. Above, in a spectacular dome, faded gods and goddesses romped in a slightly peeling blue sky. ‘Oh, how lovely!’

‘Yes. But in rather bad repair, like so much of the house. There are ten bedrooms.’ Mr Syms indicated the upper floors with a brisk wave of his hand. ‘I’ve had the master bedroom and Her Ladyship’s suite made up for you.’

He marched on into the dining room, an echoing, conventional affair with a long dining table tucked into the bay-fronted window overlooking the fountain and front lawns. ‘The dining room,’ he announced, heading almost immediately through another door, into a drawing room with an elaborate vaulted ceiling, library bookcases, soft yellow walls and a grand piano. Marble busts adorned the plinths between shelves; two ancient Knole settees piled with cushions offered a comfortable refuge to curl up with a book and a cup of tea. A ginger cat basked contentedly in a square of sun on top of an ottoman, purring loudly.

‘The drawing room.’

He swung another door open wide.

‘The sitting room.’

And so the tour continued, at breakneck speed; through to the morning room, the study, gun room, the fishing-tackle room, the pantry, the silver room, the main kitchen with its long pine table and cool flagstone floors leading into the second, smaller kitchen and cellars. It was a winding maze of a house. No amount of cleaning could remove the faint smell of dust and damp, embedded into the soft furnishings from generations of use. And despite the heat, there was a permanent chill in the air, as if it were standing in an unseen shadow.

Mr Syms returned to the sitting room, unlocking the French windows. They stepped outside into a walled garden at the side of the house where a rolling lawn, bordered by well-established flower beds led to a small, Italian-style rose garden. It was arranged around a central sundial with carved stone benches in each corner. In the distance, the coastline jutted out over the bay; the water sparkling in the hazy afternoon sun.

Mr Syms guided them to the far end of the lawn where a table and chairs were set up under the cool shade of an ancient horse-chestnut tree. Tea things were laid out; a blue pottery teapot, two mugs, cheese sandwiches and a plate of Bourbon biscuits.

‘How perfect!’ Cate smiled. ‘Thank you!’

Mr Syms didn’t sit, but instead concentrated, going over some internal checklist.

‘The housekeeper, Mrs Williams, thought you might need something. Her flat is there.’ He indicated a low cottage at the back of the property. ‘She’s prepared a shepherd’s pie for tonight. And apologises if either of you are vegetarians.’ He checked his watch. ‘I’m afraid, Mr Coates, that I have another appointment and must be going. It’s my understanding that you and Miss Albion will be spending the night, possibly even two, while you value and catalogue the contents of the house. Is that correct?’