This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

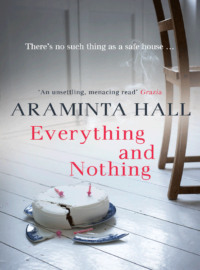

Read the book: «Everything and Nothing»

ARAMINTA HALL

Everything and Nothing

Dedication

To my own perfectly imperfect family, Jamie, Oscar, Violet & Edith

Epigraph

The grey-haired man began to laugh again. ‘First you tell me that marriage is founded on love, and then when I express my doubts as to the existence of any love apart from the physical kind you try to prove its existence by the fact that marriages exist. But marriage nowadays is just a deception.’

The Kreutzer Sonata, LEO TOLSTOY

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Begin Reading. . .

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Begin Reading. . .

The tube spat Agatha into one of those areas where people used to lie about their postcodes. Although why anyone would ever have been ashamed to live here was beyond Agatha’s understanding. The streets were long and wide, with trees standing as sentry guards outside each Victorian house. The houses themselves towered out of the ground with splendour and grace, as if they had risen complete when God created the world in seven days, one of Agatha’s favourite childhood stories. They were stern and majestic, with their paths of orange bricks like giant cough lozenges, their stained-glass window panels in the front doors reflecting light from the obligatory hallway chandeliers, the brass door fittings and the little iron gates which looked as correct as a bow tie at a neck. They even had those fantastic bay windows, which looked to Agatha like a row of proud pregnant bellies. You never saw anything like this where she had been brought up.

The address on the piece of paper in Agatha’s hand led her to a door with an unusual bell. It was a hard, round, metallic ball which you pulled out of an ornate setting and was probably as old as the house. Agatha liked the bell; both for its audacity in daring to protrude and its undaunted ability to survive. She pulled the ball and a proper tinkling sound rang somewhere inside.

As she waited, Agatha tried to get into character. She practised her smile and told herself to remember to keep her hand movements small and contained. It wasn’t that she couldn’t be this person or even that this person was a lie, it was just that she had to remember who this person was.

The man who opened the door looked ruffled, like he’d had a hard day. A girl was crying in the background and he was holding a boy who looked too old to be sucking on the bottle clamped in his mouth. The house felt cloyingly warm and she could see the kitchen windows were all steamed up. Coats and shoes and even a bike lay across the hall.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Christian Donaldson, as she supposed him to be, ‘we’re in a bit of chaos. But nothing terminal yet.’

‘Don’t worry.’ Agatha had learnt that people like the Donaldsons secretly, or maybe not even secretly, liked to appear chaotic.

He held out his spare hand. ‘Anyway, Annie, I presume . . . ’

‘Agatha actually.’ His mistake unnerved her and she tried to save herself from instant rejection. ‘Well, Aggie really.’

‘Shit, sorry, my fault. I thought my wife said . . . she’s not home yet.’ His flustered response reassured her. They were just one of those families. He stood back. ‘Anyway, come in, sorry, I’m keeping you standing on the doorstep.’

The wailing girl was sitting at the kitchen table and the kitchen itself looked as though a small and mutinous army had attacked every cupboard, spilling all their contents onto every available surface.

‘Daddy,’ screamed the girl from the table, ‘it’s not fair. Why do I have to eat my broccoli when Hal doesn’t have to eat anything at all?’

Agatha waited with the child for the answer, but none came. She hated the way adults found silence sufficient. She looked at the man whom she hoped would employ her and saw a thin film of sweat on his face which gave her the confidence to speak. ‘What’s your favourite colour?’

The girl stopped crying and looked at her. It was too interesting a question to ignore. ‘Pink.’

Predictable, thought Agatha. Her daughters were going to like blue. ‘Well, that’s lucky because I’ve got a packet of Smarties in my bag and I don’t like the pink ones, so if you eat that one tiny piece of broccoli I’ll give you all my pink Smarties.’

The girl looked stunned. ‘Really?’

Agatha turned to Christian Donaldson, who she was relieved to see smiling. ‘Well, if that’s okay with your dad.’

He laughed. ‘What’s a few Smarties amongst friends?’

Christian couldn’t stand the girls who moved into his house to look after his children. He wondered what he looked like to this one. He wanted to explain that he was never usually home at this time, that it was only the result of a massive row he’d had with Ruth at the weekend. Something about his children and responsibility and the fact that she’d be sacked if she took another day, all of which simply boiled down to how bloody brilliantly self-sacrificing she was and what a selfish shit he was. Besides, after a full day of childcare he felt like his kids had flung him against a wall and he was too tired to think of anything to say. And where the fuck was Ruth anyway?

The girl didn’t want tea but she did allow Betty to lead her into the part of the sitting room overrun by plastic toys. Christian pretended to busy himself in the kitchen, shifting piles of mess which Ruth would properly home later.

Other people in his house always shrunk it for Christian. It became all it was in the eyes of guests. Two small rooms knocked together at the front and a kitchen unimaginatively extended into the side return. Overcrowded bedrooms and a space squeezed into the roof. It felt like a fat man who had eaten too much at lunch, gout ridden and uncomfortable.

When he had been fucking Sarah they had always met at her flat, for obvious reasons. But that had been worse. As he had lain on her creaking double bed, he would feel old and foolish surrounded by posters for bands he didn’t even recognise, stuck onto walls whose colour he knew hadn’t been chosen by anyone who lived there. He would find himself perversely longing for the subtle shades and carefully crafted beauty of his own house. And what a trick for his mind to play because he had so hated Ruth when she had cried over builders running late or been more excited by the colour of a tile than the touch of his hand.

There had been a park bench which had also reminded him of his wife during that time. Predictably, because don’t all affairs need a park bench, he would sometimes meet Sarah there and it had an inscription which read: For Maude, who loved this park as much as I loved her. He had imagined an old man whittling the letters to make the words, tears on his gnarled face, a lifetime of good memories in his head. All of which was of course crap as no one had good memories any more and the bench had no doubt been gouged by some council machine.

Not that it would have been enough to stop him anyway. Ruth had been so easy to fool it had almost cancelled out the excitement, and this annoyance had spurred him on. He had always worked unpredictable hours and his job in television had often led him far from home, so staying away over night was commonplace in their marriage. More than anything though he had felt vindicated. He told himself that Ruth had always smothered him, that she had repressed his true nature, that his real self was a fun-loving, carefree guy who had never wanted to be tied down. That ultimately someone like Sarah suited him far better.

She probably hadn’t, though. Although he still felt muddled, still found it hard to get any clarity around a situation that had descended into such stomach-churning detritus, it was hard to place any decent feelings. Two women pregnant at the same time and yet only one child to show for it. One strange little boy who still, at the age of nearly three, never ate, hardly spoke and followed your movements like eyes staring out of a painting. Christian worried that Hal had absorbed his mother’s misery in the womb in the same way that some babies are born addicted to heroin. A key turned in his front door and he realised that his hands had grown cold in the sink.

Ruth was always going to be late, but still she felt like a naughty child. Christian wouldn’t understand. She hadn’t even got the necessary words to explain why she had always known she wouldn’t leave the office at six, but had arranged the interview for seven. Not that she had been able to predict the rain, of course, which jammed the tube so you felt you would suffocate even in the ticket hall. It unsettled her; the way the rain lashed at the city nowadays, the way the clouds darkened so quickly and furiously, without any warning. She couldn’t remember it having been like that in her own childhood and she fretted over what she would tell her children about the world they were growing into.

She could tell the girl was already there, just as she could tell the house had sunk even lower. Ruth was used to leaving every morning closing her eyes to the tangled sheets falling off all the beds, the washing exploding out of the laundry basket, the food drying onto plates in the sink, the fridge compartments that needed cleaning, the dirty hand prints on all the windows, the fluff which multiplied like bunnies on the stair treads, the unre-turned DVDs scattered around the machine, the recycling which needed transporting from beside the bin to the boxes at the front of the house, the name-tags not sewn into Betty’s uniform. The magnitude of these tasks pulled at her back like a bungee rope all the way to her offi ce. But this evening she thought they might at last have tipped from mess to squalor. She wondered if Christian had done it on purpose to punish her for keeping him from his stupidly important job where he got to pretend that he was an indispensable person every day of the working week. Light household duties, she had written in her advert; she wondered what that might consist of and decided on the usual laundry so that at least they would look like they held it together to the outside world. And food shopping; they had to eat, after all.

From the hall Ruth could see the girl on the floor with Betty. She looked so young, they could almost have been playmates. On the tube coming home Ruth had been hit by panic. Going back to work after two weeks immersed in childcare had jolted her and filled her mind with doubts. The final showdown with their last nanny was also still lodged in her brain. The weeping girl standing in the doorway with her bags already packed and her mind resolutely made up, saying she couldn’t take one more night listening to Betty screaming. I have to get some sleep, she’d said, forgetting surely that Ruth was the one who got up to the little girl hour after bloody hour, scaling each night like a mountain climber.

Then last week she’d found herself checking Christian’s texts, something she hadn’t done in over a year. Worse than the checking though was realising that she almost wanted to find something. That it would be more exciting than washing another load of socks or trying to make supper out of whatever was in the fridge. And she was too old to still be a deputy editor, wasn’t she? It had been a terrible mistake to have refused the editorship Harvey had offered last year.

‘I don’t get it,’ Christian had said when she’d wept to him over her final decision. ‘What’s the big fuss? If you want the job, do it; we’ll get more help. No big deal.’

‘No big deal?’ she’d repeated, the tears straining again against her better judgement. ‘Do you think your kids are no big deal?’

‘What do you mean? Why are you bringing the kids into this?’

‘Because obviously I’m not refusing the job for me.’

He’d sighed. ‘Oh God, please not the martyr act again. Why is your refusing the job anything to do with the kids?’

Ruth felt consumed by an annoyance so intense she worried she might stab her husband. ‘Because if I take this job I’ll basically never see them.’

‘What, like all the quality time you spend with them now?’

‘How can you say that? Are you saying I’m a bad mother?’ Ruth had felt as though she was losing her grip on the situation.

Christian poured himself more wine. ‘I’m saying that we both made a choice, Ruth. We both decided to pursue our careers. I’m not saying we’re right or wrong. I’m saying you can’t have it all.’

‘You seem to manage it.’

‘No, I don’t. I’d love to see more of them, but we bought a house we couldn’t afford because you wanted it and we have a massive mortgage.’

‘It wasn’t only me, I never forced you into buying it.’

‘I’d have been as happy somewhere smaller.’

But the truth was that Ruth was sure Christian did have more than her. He pursued his career with a single-minded focus and, as a result, had done very well. He didn’t feel guilt at being out of the house all day and so he could relish the time he spent with their children. For some primeval reason it didn’t appear to be his role to know about when their vaccinations were due or even whether or not they should have them. He didn’t feel compelled to read endless parenting books or to worry that his working caused behavioural problems in his children. He never took a half day to attend Christmas concerts or sports days, but if he happened to be around and turned up everyone noticed and thought he was a great father.

It was all these little injustices which wore away at Ruth until she felt as though her marriage was nothing more than a rocky outcrop being relentlessly lashed by the sea. And it wasn’t even as if she could articulate any of this to Christian, or he to her. And so they flailed along like blind bumper-car drivers, occasionally causing each other serious injury, but mainly just cuts and bruises.

‘You got her name wrong,’ said Christian as soon as Ruth walked into the sitting room. ‘It’s Aggie.’

Ruth sat down without even pausing to take off her coat because both Betty and Hal were trying to climb on her. ‘Oh, I’m sorry, I must have misheard you on the phone.’

‘I couldn’t get away.’ Ruth realised she was apologising as much to Christian as Aggie. ‘You know, first day back and all that.’ She smiled at Aggie and mouthed over Betty’s head, ‘It’s been a nightmare.’ Who was she trying to be here?

‘Why don’t you put a DVD on for them?’ she said to Christian, and then felt the need to say to Aggie, ‘We don’t normally let them watch TV after five, but we’ll never finish a sentence if we don’t.’

The girl nodded, watching the children fight over which DVD they were going to see. In the end Christian lost his temper. ‘Look, I’m putting on Toy Story. It’s the only one you both like.’

Betty started to wail but they all kept their smiles fixed.

‘It’s either this or nothing,’ Christian shouted as he jabbed at the machine.

‘So.’ Ruth turned to Aggie. ‘Sorry about that. Right, well, let’s see. I suppose Christian has filled you in on us a bit.’

The girl blushed and tried to answer but nothing came out.

‘Sorry, Betty commandeered her,’ said Christian.

Ruth felt defeated before she’d even begun. ‘So you haven’t said anything about Hal yet?’

‘No, not yet, I was waiting for you.’ And there it was, the perfect get-out.

Ruth composed herself. ‘Sorry, Aggie, let me explain. Hal’s nearly three and he’s never eaten anything. Not ever. He lives off bottles of milk. I’ve taken him to the doctors but they say he’s perfectly healthy. Maybe a bit behind developmentally; I mean, he hardly speaks, but apparently that’s not overly worrying. We don’t know what to do next. I’ve got an appointment with a great nutritionist in a few weeks, but I guess our most important question to you is how you feel about food?’

Agatha looked at the back of Hal’s head. She liked the idea of looking after a freak. And she’d babysat and nannied for enough of these ridiculous women to know what to say. She imagined the Donaldsons’ fridge, all green and verdant and organic at the top, but beating in the cold heart of the freezer would be the fat-laden, salt-addled reality.

‘Well, I think what you feed kids is reflected in their behaviour. Obviously I try to get them to eat five fruit and veg a day and I only buy organic, but I’m not evangelical or anything. I think the odd sweet or biscuit is fine.’

Ruth nodded approvingly while Christian stared oblivious out of the window. ‘That’s pretty much how we feel, but we’ve had such problems with Hal. The doctor says we should go with it for now. She even told me to try giving him things like chocolate to get him used to the idea of eating. But that’s absurd, don’t you think?’

Agatha thought it sounded sensible. She had been brought up on a diet of frozen burgers, oven chips and chocolate. Pot Noodles, if she was lucky. And it hadn’t done her any harm. But of course she shook her head disapprovingly.

‘And what about discipline, where do you stand on that?’

‘I do believe in rules.’ Agatha could remember her last employer screaming at her children after telling Agatha in her interview that she thought a raised voice was a stupid voice. They were fucking priceless these women. ‘But I think they should be rules we’d obey anyway, like be polite and kind and don’t hit or snatch, those sort of things. And I don’t like to threaten anything I’m not prepared to carry out.’ Agatha wasn’t confi dent she should say this as Ruth Donaldson was in all likelihood another of those crazy women who wouldn’t be left in charge of their kids if they lived on the local estate but somehow got away with it because they lived in half-a-million-pound houses and knew a few long words. But then again these women were usually addicted to parenting programmes and so had a fair idea for how they should be behaving even if they couldn’t manage it themselves.

‘I put on the advert light household duties, are you okay with that? I meant a bit of laundry and keeping things a bit straight and maybe a bit of food shopping.’

‘Oh, absolutely, that’s fine. Of course I’d do that.’ That was the part Agatha liked the best. Putting everything into its right place. Sorting the house and making her employers marvel at her efficiency. She had been a cleaner many times in her life and she always proved herself indispensable. A lot of these families lived in near slum conditions. Agatha had learnt that they were the sort of people who you’d look at from the outside and wish you could be part of them. You’d covet their clothes and their house and coffee maker and £300 hoover and fridges in bright colours. But they couldn’t even flush their own toilets, most of them. They didn’t understand that the world had to be neat and that keeping things in order was very simple.

‘And as you know, Christian and I both work long hours. I try to be home for seven, but Christian never is. Are you okay with that? Maybe sometimes putting them to bed?’

‘Of course, I’m used to that.’ By the end of most jobs Agatha would have preferred it if the parents had disappeared; she liked to imagine them vaporised by their own neuroses. Handling children was always so much easier than adults.

‘So, Aggie, tell us about yourself.’

Agatha was used to this question now, she knew these types of people liked to pretend they cared, but it still roused a dread inside her. The other answers hadn’t really been lies. It wasn’t like she was going to feed the kids crap whilst hitting them and shovelling the dirt under the sofa. She was going to be a good nanny, but she couldn’t tell these people about herself. She had experimented with a couple of answers in the past few interviews, but she’d found that if you said your parents were dead they felt too sorry for you and if you said they’d emigrated they still expected them to call. This was the first time she’d tried out her new answer: ‘I was brought up in Manchester and I’m an only child. My parents are very old-fashioned and when I got into university to study Philosophy my dad went mad. He’s very religious, you see, and he said Philosophy was the root of all evil, the devil’s work.’ She’d seen this on a late-night soap opera and it had sounded plausible, or maybe fantastic enough to be something you wouldn’t make up.

Ruth and Christian Donaldson reacted exactly as she’d expected, sitting up like two eager spaniels, liberal sensitivity spreading across their faces.

‘He said if I went he’d disown me.’

‘But you went anyway?’

Agatha looked down and felt the pain of this slight so hard that real tears pricked her eyes. ‘No, I didn’t. I could kick myself now, but I turned down the place.’

Ruth’s hand went to her mouth in a gesture Agatha doubted to be spontaneous. ‘Oh, how awful. How could he have denied you such an opportunity?’ She was longing to say that she would never do anything so terrible to her own children.

‘I stayed at home for a while after that, but it was terrible. So many rows.’ Agatha could see a neat suburban terrace as she said this with a pinched man wagging a finger at her. The air smelt of vinegar, she realised; maybe her mother had been a bad cook or an obsessive cleaner, she wasn’t sure which yet. She wondered along with this kind couple sitting in front of her how he could have been so mean. ‘I left five years ago and I haven’t spoken to them since.’

‘But your mother, hasn’t she contacted you?’

‘She was very dominated by my dad. I think they’ve moved now.’

‘Do you have any siblings?’

‘No, it’s just me. I’m an only child.’

‘Poor you,’ said Ruth, but Agatha could already see her working out that they were getting a nanny who was clever enough to get into university, and for no extra cost.

When Agatha got back to her grotty room in King’s Cross she felt tired and drained. She was still trying to work out why she might have told the Donaldsons she was called Aggie when no one had ever called her anything but Agatha. She supposed it must have sounded friendlier and she’d have to go with it now. Her room-mate’s mobile was ringing. She answered with a curt hello and then started waving madly at Agatha. Lisa was prone to wild mood swings, so Agatha didn’t take any notice until she heard what she was saying.

‘Oh, she was amazing, we were so sad to lose her . . . yes, she had sole care of both of them, I work full time . . . No, it was because we decided to move out of London, to get the children a bigger garden.’ Lisa started to pretend she was sucking a massive penis as she said this which annoyed Agatha, she fucking had to remember the script. ‘In fact, we nearly stayed just to keep her.’ Fake laughing, Lisa miming sipping a glass of champagne. ‘Oh, it’s so hard, isn’t it, all that juggling.’ Lisa put her hand over the phone and mouthed fucking tosser at Agatha, who smiled obligingly. If Lisa fucked this up she might hit the stupid bitch. ‘No, no, ring anytime, but really, I couldn’t recommend her highly enough.’ Lisa threw her phone onto the bed and made a sucking noise with her teeth. ‘Man, those posh types are gullible. They almost deserve to be done over, innit?’

‘Thanks,’ said Agatha, fishing her last twenty-pound note out of her wallet and handing it over to Lisa. If you wish for something hard enough it will happen, someone had once told her, or maybe she’d seen it on a film. She didn’t care, all she cared about was wishing herself out of this hellhole and into the Donaldsons’ home as quickly as possible.

‘Do you want Indian or Chinese?’ asked Ruth as she rooted through the spare kitchen drawer overflowing with wrapping paper, old packets of seeds, a spilt box of pins, paint colour charts and numerous other bits of tat for which they would never again find a use.

‘Don’t care,’ answered Christian, pouring them both wine. ‘I’m knackered.’

The children had only been in bed for fifteen minutes and Ruth was sure Betty would be down any minute with some excuse like wanting a glass of water and then she’d lose her temper, which would mean the only real time she spent with her daughter would be about as far from quality as you could get. But how long could she be expected to go on surviving on so little sleep? It wasn’t a euphemism to say that sleep deprivation was a form of torture; there were doubtless thousands of people right now in prisons around the world sleeping more than she was. Christian had developed the ability to sleep through Betty’s crying and she’d long since stopped trying to wake him. Survival of the fittest, she found herself thinking most nights, dominant evolution. It was no wonder Betty cried all day; Ruth would do the same if she could.

Christian noticed it was nearly nine and couldn’t help feeling as if he’d wasted his day. He’d lied to Ruth earlier and told her he’d managed to get a bit of work done when all he’d accomplished was approving the advert for the new admin assistant for his department. He felt physically wrecked. Why did Betty cry so much? And why wouldn’t Hal eat? He knew they should talk about it but also felt too tired to bring up these explosive topics with Ruth. Because his wife always had the energy for a fight, if nothing else.

‘So what did you think of her?’ she was asking.

‘Fine, how about you?’

‘I thought she was great and her referee couldn’t give her enough praise.’

‘Right.’ Christian sat down at their long wooden kitchen table, which had been designed for a much larger and grander house and made their kitchen feel as foolish as an old woman in a mini skirt. Ruth had bought it from an antiques fair in Sussex where they’d walked round a massive field filled with Belgians selling old bits of furniture which would be burnt in their own country but went for hundreds of pounds over here. He could remember the Polish builders laughing at Ruth when they’d been renovating the house and a pair of wall lights had gone missing and she’d asked the foreman if maybe one of the men might have taken them. To us, he had said, throwing his hands in the air, they are pennies. Christian had felt hated by those men. Actually not hated, more contemptuous. He knew they laughed at him in their own language, wondered at what mad man would spend thousands on a fucking house.

‘But do you think we should hire her?’

Christian tried to think of a reason to hire or not to hire. Their last nanny had seemed great until she’d left with no more warning than the time it had taken to say the words. He couldn’t even picture the new girl properly, but he did remember that she’d made Betty stop crying. ‘She seemed great. Do we have a lot of choice?’

Ruth looked grey. ‘No, but is that a good reason to hire someone to look after your children?’

‘Look, do it. If it doesn’t work out we’ll re-think.’ He put his hand over hers and got a flash of passion from the touch of her skin. She did that to him sometimes.

She tucked her hair behind her ears. ‘Okay, good plan, Batman.’ It was what she said to Hal and it sucked his desire right out of him.

Agatha’s room in the Donaldsons’ house was so perfect it made her want to cry. It was right at the top, which made her feel cocooned, all those people between her and the world. And it was painted in a light blue that she had once read was called duck-egg blue, which was a colour she could imagine cosy American mothers using. Jutting out of the far wall was a large white wooden bed festooned in squishy, fluffy cushions which gave the impression you were floating in the clouds as you drifted off to sleep. And her own little bathroom behind a door she’d thought was a cupboard, where Ruth had kindly put some expensive-looking lotions and potions. Best of all though the only windows were on either side of the roof so you couldn’t see the street and instead could stare at the sky in all its different guises and pretend you were in any number of countries and situations. It was the sort of room Agatha had dreamt of, but never imagined she’d inhabit.

Ruth and Christian seemed very concerned she had everything she needed and immensely grateful that she had agreed to take the job, when it should have been the other way around. She smiled and laughed all weekend, but was itching for them to leave on Monday morning so she could get stuck in. She had plans for the house and kids. First she would sort and tidy and then she would get Betty to stop crying all the time and finally she would get Hal eating. Life was simple when you set out your targets in basic terms.

The house was dirtier than she had given it credit for. The Donaldsons’ cleaner had been taking them for a ride because anywhere you couldn’t see had been left untouched for years. Under the sofas and beds were graveyards for missing items which Agatha couldn’t believe had ever been of any use to anyone. The inside of the fridge was sticky and disgusting and the lint in the dryer must surely be a fire hazard. All the windows were filthy and the wood round them looked black and rotten, but really only needed wiping with a damp cloth. The bread bin was filled with crumbs and hard, rotten rolls and the freezer was so jam-packed with empty boxes and long-forgotten meals that it looked like it was never used. There were clothes at the bottom of the laundry basket which smelt mouldy and which Agatha felt sure Ruth would have forgotten she owned, simply because they needed hand washing. Cupboards were sticky from spilt jam and honey, and the oven smoked when you turned it on because of all the fat that had built up over the years. Agatha would never, ever let her future home end up like this. She would never leave it every day like Ruth did. She would never put her trust in strangers.

‘How’s the new nanny?’ Sally, her editor, had asked as soon as Ruth had arrived at work that first Monday, to which she’d been able to reply truthfully, ‘She seems great.’ And at first she had, in fact still now, a week since Agatha had started, she seemed great. It was just that she made Ruth feel shit. Ruth suspected her feelings to be pathetic, but the girl was too good. Her house had never been so clean, the fridge never so well stocked, the food she cooked every night was delicious and the children seemed happy. It was a working-mother’s dream scenario and to complain was surely akin to madness; but before Aggie she had always found something perversely comforting in bitching about the nanny, in secretly believing she could do a better job. Ruth knew enough however to know that she undoubtedly could not have done a better job.

The free sample has ended.