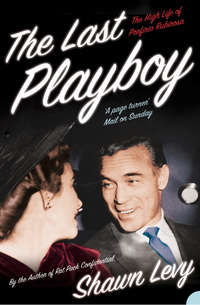

Read the book: «The Last Playboy: The High Life of Porfirio Rubirosa»

SHAWN LEVY

The Last Playboy

THE HIGH LIFE OF PORFIRIO RUBIROSA

DEDICATION

FOR VINCENT, ANTHONY, AND PAULA,

WITHOUT WHOM THERE WOULDN’T BE MUCH POINT

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

THE LAST PLAYBOY

ONE IN THE LAND OF TÍGUERISMO

TWO CONTINENTAL SEASONING

THREE THE BENEFACTOR AND THE CHILD BRIDE

FOUR A DREDGE AND A BOTCH AND A BUST-UP

FIVE STAR POWER

SIX AN AMBUSH AND AN HEIRESS

SEVEN YUL BRYNNER IN A BLACK TURTLENECK

EIGHT BIG BOY

NINE SPEED, MUTINY, AND OTHER MEN’S WIVES

TEN HOT PEPPER

ELEVEN COLD FISH

TWELVE CENTER RING

THIRTEEN CASH BOX CASANOVA

FOURTEEN THE STUDENT PRINCE IN OLD HOLLYWOOD

FIFTEEN BETWEEN DYNASTIES

SIXTEEN FRESH BLOOM

SEVENTEEN RIPPLES

Keep Reading

Inspirations, Sources, and Debts

Works Consulted

Searchable Terms

About the Author

Praise

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

THE LAST PLAYBOY

This, he reckoned, must be what they called a joint.

Normally in New York he didn’t go into joints. The Plaza, El Morocco, the Stork Club, the Copa, “21”: That was the sort of thing he liked. He was in the city so rarely, he was only interested in the best of it.

In Paris, of course, he knew such places, cafés and bars and clubs where you might meet a killer or somebody with an interesting business idea or a woman who would change your life—or maybe just a few minutes of it. But this, this had something of the savor of a café back home, one of the places along El Conde—an air of abandon and indulgence and danger. It was dark, spare, ominous. He liked it.

Besides, the best places were, how to say it, a little chilly right now. All this talk: newspapers and the television and people on the street and the ones they called “the right people.” The snobs and the writers hated one another, but to him they seemed very much the same.…

He had nothing to fear, nothing to hide, nothing to be ashamed about. But he didn’t need the headache of answering questions and being stared at by gossips and trying to figure out who would talk to him and who wouldn’t.

This place would do just fine, then: convenient, quiet, anonymous.

He had agreed to meet the newspaperman because he needed to get his own story out and he was assured by friends that he could trust the fellow. Earl Wilson he was called: owl-faced, a little thick in the waist, an easy laugher, a good listener.

Right now, he needed someone to listen—and then go and tell it in the way he wanted it told. All around New York the most horrible things were being said: He was a threat to his new wife; he was only interested in her money; he was some kind of villain or crook or gigolo. People knew nothing about them: He had known Barbara for years; she was charming, vibrant, delicate, cultured, creative; why shouldn’t he truly love her? And in Las Vegas, that madwoman with her press conferences and her eye patch and her ridiculous lies about what he had said to her and what he felt. No wonder people were giving him funny looks.

No, his own voice had to be heard, and for that he needed someone neutral, someone who would tell the truth about him: Earl Wilson, his new best friend.

They sat at midnight in a booth in the back of the Midston House bar on East Thirty-eighth Street, one freezing night, one of the last of 1953. They drank scotch—scotches—and he nibbled from the bowl of popcorn the waitress had put on the table when they sat down. “My bachelor dinner,” he joked.

Some pleasantries, and then the questions.

This was Barbara’s fifth wedding and his fourth. Why would anyone expect it to work out?

“Wonderful Barbara brought something new and different into my life,” he said, “and I will not be like her other husbands. I will make her happy at last.”

Next, Wilson wanted to know, like they all did, about the money: Barbara was said to have $100 million; was he after it?

“Riches to me don’t count,” he said sweetly. “I don’t need anybody’s money. I have plenty of my own. We will be married like civilized people under the law of separate property. What property she has is hers and what property I have is mine.”

He didn’t, of course, mention the prenuptial contract he had signed that very afternoon: $2.5 million on the barrelhead, plus future considerations, of which he also had plenty of his own. Let the great reporter find some things out on his own.…

“Is she ill?” Wilson asked.

“Ill?”—a laugh, with a little scorn in it, which he caught almost as quickly as he’d shown it. “Not at all, she’s the healthiest woman—it’s fantastic! Yes, she was in Doctors Hospital, but only to rest. And now, my God, what a vitality! She’s so strong that when she shakes hands I say, ‘My God, where did you get all that weight?’”

“But I thought she was slender from loss of weight.…”

“Oh, no. I don’t like skinny girls—and she’s all right!”

They laughed a little and Wilson wrote.

And what about this business in Las Vegas, Zsa Zsa claiming he had asked her to marry him and that he had hit her when she refused him?

Now he was impatient.

“Zsa Zsa is just trying to get publicity out of Barbara and me, and I don’t think it’s ladylike.”

The writer kept his eyes on his notepad, scribbling, silent.

The man seated across the table remembered who he was—a public figure, a glamorous consort, a world-famous lover, an intimate to power and wealth and sensation. He could breeze through it. He would have to get the smile just right.…

“Barbara is such an intelligent girl,” he continued. “She understands human nature so well; she’ll know it’s all ridiculous. She’s one of the most intelligent women anybody ever met.”

They returned to small talk: who would attend from the bride’s family, where would they honeymoon, where would they live.

And then, nicely buzzing, he rose and excused himself.

Tomorrow was going to be a big day.

How did they say it in English?

Like a zoo.…

ONE

IN THE LAND OF TÍGUERISMO

When he sat down and tried to remember it all, in the ’60s, near the end of his life, he began, naturally, with his childhood, as he could retrieve it: a series of brief scenes, like film clips, set in his intoxicating, perilous homeland—random moments, yet with a cumulative impact that shaped him irrationally, subliminally, imparting to him tastes and biases that he never lost. A man of the world, he forever defined himself by reference to a specific place.…

Rifle fire; early morning; a child springs up in bed. “At most,” he remembered later, “I was three years old.”

Not long after, in the dead of another night, the child startles awake once again, panicked to find himself alone. “I was in the habit of sleeping with a cat.” He leaves his bed to seek his feline bedmate, and is shocked to find strangers everywhere. “The house was filled with armed men asleep in the hallways.”

And maybe a year later still, a mounted rider approaches. “Without getting off his horse, he took me in his great big hands and pulled me up to its neck, in front of him. One click of his tongue, and we were off! ‘Careful Pedro, careful! He’s so little!’ shouted my mother. My father laughed. The night was gentle and sweet. I had the horse’s mane gripped in my hands. I heard his hard breathing. I wished the corral would never end.”

Gunshots; soldiers; a strongman; a horse; a shouting woman; the thrill of speed; the danger; the Cibao Valley of the Dominican Republic in its Wild West phase, circa 1913: the earliest flashes of memory in the mind of Porfirio Rubirosa.

In the early twentieth century, when a little boy was being imprinted by these memories, the Dominican Republic was, as it had been for centuries prior, a place where fortunes might be made and dominions might be established—but only after painful struggles that were not always won by the most honorable combatant. It was a place that tended to favor unfavorable outcomes. Indeed, despite the noble charge and historic pedigree of the first white men who stumbled on it, the first European to settle the island and live out his days there was, in all likelihood, a rat.

Just after midnight on Christmas Day, 1492, a Spanish caravel gently foundered onto a coral reef beside the large island that its passengers had dubbed Española—Hispaniola in English—the sixth landmass it had encountered in the dozen weeks since departing the Canary Islands.

By dawn, the ship had broken up and sunk.

At that moment, Christopher Columbus had a complete fiasco on his hands.

A nondescript Genoese merchant sailor who made his home in Portugal, Columbus had sufficiently gulled the queen of Spain with his outlandish theories about a sea route to Asia that she arranged a backdoor loan for his enterprise from her husband’s treasury. Isabella invested enough in his pipe dream for Columbus to acquire supplies, a crew, and three ships—the largest of which, the Santa María, had just become the first in several centuries of fabled Caribbean wrecks.

Gold Columbus reckoned he would find, and jewels and spices and a path to the riches of the other side of the world that would make trade with the hostile Moors unnecessary. But to date, he had gleaned significantly less than his own weight in treasure, and with the Santa María sunk, he was down to two ships for the trip home.

So he formed a landing party (which included at least one stowaway rat, whose bones—distinct from those of native species—would be discovered by archeologists centuries later), and he went ashore. There he shook hands with the leader of the native Tainos, accepted a few gifts, and founded a colony, named La Navidad in honor of its Christmas Day discovery. He looked around for a mountain of gold and, seeing none, packed up the Niña and Pinta and went home.

Ten months later, having raised enough capital to fund a fleet of seventeen ships, he returned, intent on exploiting the fonts of gold he believed the island nestled. In January 1494, he founded a second settlement, named La Isabela for his patroness, and used it as a base from which to explore the interior of the island.

Specifically, Columbus was curious about the Cibao, a highland valley that meandered eastward along a river from the northern coast through two mountain ranges and met the sea again in swamplands in the east. On his previous trip, he’d been told that the valley was home to fields where chunks of gold as large as a man’s head lay about just waiting to be gathered. He forayed inland and found the valley—he labeled it La Vega, “the open plain”—but there was no gold. He was nevertheless impressed: The soil was rich, the climate mild, the river navigable, the mountain ranges, particularly to the south, formidable. If he had been a settler and not a buccaneer, he might have colonized the place for ranching and farming. But his priority was raw wealth. He moved on.

Columbus would make two more trips to Hispaniola, still looking for gold, still luckless. He and his men would found the city of Santo Domingo on the southern coast, a deep harbor from which Spain would rule the Caribbean and the Americas. In the coming centuries, the island, genocidally cleansed of natives, would be a keystone of the Spanish slave trade and an important colony of plantations. The Cibao would yield real wealth—fortunes based in coffee, cattle, sugarcane, tobacco—but nobody would ever again venture there in search of treasure.

Indeed, those who did choose to settle there were often lucky just to keep their heads. For hundreds of years after Columbus, the island, despite its import as a staging ground, would be overrun by a continual string of colonial and civil wars and the never-ending scourges of disease, poverty, rapine, and neglect.

Hispaniola fell into ruin in large part because it was, uniquely, colonized by two European powers. The Spanish contented themselves with dominating the eastern side until the French established a foothold in the west in the mid-seventeenth century. The island, long neglected by Spain in favor of colonies that yielded more in the way of obvious riches, suddenly seemed a valuable commodity, a point of contention. Back and forth forces of the two rivals fought, trying bootlessly to vanquish one another until the island was split by treaty in 1697 into two nations: Haiti and Santo Domingo. The plantations of Haiti, under French guidance, prospered, while Santo Domingo lapsed into a tropical torpor more typical of Spanish rule: Slaves bought their freedom and married with Europeans; infrastructure, never the strong suit of Spanish colonialism, was neglected; the economy declined into stagnation. When the Haitian slave rebellion led by Toussaint L’Ouverture spilled eastward over the border in 1801, there was little resistance. Under a rampage of murder, rape, and butchery, Santo Domingo simply fell into French hands for twenty bloody years.

Then a hero arose: Juan Pablo Duarte, a homegrown nationalist who sought freedom not only from the Haitians but from Spain. Starting as a governor of the Cibao, he routed the Haitians and the Spanish, but he failed to bring true unity to the nation. From the expulsion of the Haitian forces in 1844 through the expulsion of the Spanish in 1865 and onward toward the new century, the Dominican Republic, as it had been renamed, was ruled by chaos. Presidents came and went in brief, nasty succession; unrest and poverty were epidemic; and a species of tribal warfare ground on. There were puppet heads of state, bloodthirsty chieftains, coups and battles and massacres and ambushes and ceaseless conflicts. It seemed the destiny of the country always to roil.

Into this quagmire, in San Francisco de Macorís, a small city of the swampy eastern portion of the Cibao, Pedro Maria Rubirosa was born in 1878. The Rubirosas were an educated family, with a tradition of public service. But in this wild era, public service meant choosing a side in the never-ending civil wars. Although he was well schooled, by the time he was in his teens, Pedrito Rubirosa was riding with bands of soldiers. And by the time he was in his twenties, he was leading them.

Half a century later, his son regarded a tintype of his father from these days: “In the photograph in my hands, my father already shines like an adult. With his strong cheekbones, his powerful head, his thick moustache, his gaze falls arrogantly from a height of five-foot-ten. He doesn’t seem at all an adolescent: he is a man by deed and right. They called him Don Pedro.”

Don Pedro, his son related, “was always in a campaign. It was the time of basements stocked with rifles and houses filled with soldiers. In effect, my father negotiated a ceaseless labyrinth of skirmishes, assaults, forays, and guerilla attacks.” And through a combination of personal qualities and historical accidents, he became, in the military algebra of the era, a general. In this context, mind, a general wasn’t a professional soldier promoted after of a long career of battle and governance. He was, rather, the smartest, luckiest, boldest in his troop, responsible for arming, feeding, and housing his men, and for strategizing and liaising with the other bands of soldiers with which they were allied. It was a position earned as much with guts as brains. “A general who didn’t march in front of his men didn’t exercise great dominion over them,” Don Pedro’s son said. “This explains why Dominican officers rarely died in bed of old age, like their European colleagues, and why rapid promotions permitted a youngster of 20 to become a general.”

But there was another quality to Don Pedro, even more important than his daring or his brains or the poor luck of his senior colleagues. As his son put it, “One had to be a tiger to command a group of tigers.”

Tiger: tigre in Spanish, tíguere in the local argot, in which the word came to represent the essential defining characteristic of the Dominican alpha male. The Dominican tíguere was, like the ideal male in all Latin cultures, profoundly masculine—macho, in the Castilian—but had dimensions unique, perhaps, to the Creole culture of Hispaniola. He was handsome, graceful, strong, and well-presented, possessed of a deep-seated vanity that allowed him the luxury of niceties of character and appearance that might otherwise hint at femininity. He could move with sensuality or violence; he was fast, fearless, fortunate. A tíguere emerged well from nearly any situation that confronted him, twisted any misfortune to an asset, spun a happy ending of some sort out of the most outrageously poor circumstance; he was able, being feline, to climb to unlikely heights and, should he fall, always landed, being feline, on his feet. The tíguere bore the savor of low origins and high aspirations, as well as a certain ruthless ambition that barred no means of achieving his ends: violence, treachery, lies, shamelessness, daring, and, especially, the use of women as tools of social mobility. A tíguere always married to advantage.

If there was an element of the outlaw or the delinquent in the tíguere, if only in his early days, he could hope to transcend it and reach the highest rungs of society—indeed, it was widely understood in Dominican life that an element of tíguerismo was essential to most success. To some degree, the Dominican male, if he was true to his blood and his culture, could be permitted virtually any impudence or trespass whatever. Adultery, theft, tyranny, violence, bellicose savagery, social cruelty, excesses of libido and appetite and greed: All could be ascribed to—and forgiven as—tíguerismo.

Pedro Maria Rubirosa clearly fulfilled the role of tíguere as a warrior and man of action. But he did so as well as a lover of women. “My father was a handsome man,” the son remembered. “His form was lithe, his eyes brilliant; he shone with every aspect of a gentleman. Women admired him.”

Among those admirers was a girl from his hometown, Ana Ariza Almanzar, granddaughter of a Spanish general who had fought in Cuba. At the dawn of the new century, Don Pedro took this well-bred young woman as his wife.

They began their family with tragedy, losing at least one child before 1902; then a daughter, Ana, managed to survive the perils of tropical infancy. Three years later came a son, Cesar. The tíguere now had a male heir to boast of and to train.

It was a flush time for Don Pedro. The tyrant Ulises Heureaux, who had ruled the Dominican Republic with a ruthless hand for two decades, had been assassinated in the summer of 1899, and a period of relative calm had descended. Don Pedro’s daring, loyalty, and intelligence had recommended him to the new government, and he was appointed as governor of a string of small cities—first San Francisco de Macorís, then the coastal city of Samaná, then El Seibo, each posting finding him assigned farther from home as the warrior-politicians of the Cibao peacefully extended their influence.

In El Seibo, where he arrived in 1906, Don Pedro allowed himself the pleasure of other women. (Ana, her son would offer by way of explanation, “got fat after her first children arrived.”) With a local woman and her cousin he fathered four children en la calle, as the saying went: “in the street”: bastards.

He acknowledged them, though only one took his name. And then his duties called him back to San Francisco de Macorís, where the last of his legitimate children was born, on January 22, 1909. They named him Porfirio.

It was such a sparkling name: Porfirio Rubirosa Ariza (the Ariza a technicality, following the Spanish convention of retaining the matronym for legal purposes).

The surname was, of course, a given, and it meant “red rose.”

The Christian name, however, was something of a fancy, not a family name like that of the baby’s sister or an obviously historical name like that of his brother. There were some obscure antecedents: an ascetic Saint Porphyry of Gaza; Porphyry of Tyre, a mathematician and philosopher of Phoenicia, noted to this day for his treatises on vegetarianism and named after the purple dye for which his home city was famous (at root, the word “porphyry” refers to a shade of purple that naturally occurs in feldspar crystals). But Don Pedro and Ana probably had in mind Porfirio Díaz, the autocratic president of Mexico under whose hand that nation modernized itself into the envy of the Caribbean—a strongman whose career, like Caesar’s, would be worth emulating.

Ironically, soon after the baby was baptized, the great Díaz found himself falling into a struggle to maintain his rule—just as Don Pedro once again found himself commanding men in the field when yet another civil war broke out in the Dominican Republic in 1911. This was the campaign that formed the young Porfirio’s first memories: the rifle shots at dawn, the soldiers sleeping throughout the house, the cat that crept away in the night.

The boy would grow to remember, too, a fearful, devout Doña Ana: “My mother, who was very pious, lived at prayer … I remember her often curled up in the darkest corner of the house, praying.” Doña Ana Ariza Rubirosa may have seemed a pushover: born to a family of soldiers, married to a soldier, countenancing her husband’s infidelities, burying herself in counsel with the Virgin of Altagracia, draped demurely in black, growing plump. But there was steel in her as well. Take the way she saw to the woman who was making time with Don Pedro and then ran, unopposed, for the presidency of the ladies’ club of San Francisco de Macorís. On the day of the vote, with all the notable women of the city assembled and prepared to anoint their new leader, the outgoing president announced that she was so sure that they all approved of her successor that the election would be conducted by acclamation. “No,” came a voice. All heads turned to face the speaker, Doña Ana. “This woman is my husband’s lover,” she declared. “Under these conditions, I don’t think it’s possible to make her our president.” Shock; murmurs; a hasty conference of officials; and a new presidential candidate was impressed and elected. Ana got in her carriage, according to her son, “and returned home without saying a single word to my father about the scandalous scene she’d made. And he, after being told about the incident a few minutes later, also remained silent.”

Perhaps the scandal she’d created with her outburst was too great; perhaps Ana feared in time of civil war for the safety of her children (“Careful Pedro, careful! He’s so little!”); perhaps Don Pedro, in his mid-thirties, had grown too comfortable, too encumbered, too secure to lead troops; perhaps his intellect was recognized by his colleagues as more useful to them than his bravery; perhaps he was in flight from enemies. For whatever reason, in 1914, soon after Doña Ana’s bold gambit, the Rubirosas found themselves sailing away from their bellicose, agitated little country. Don Pedro had been named to serve in the Dominican legation in St. Thomas, the Virgin Islands.

At the age of five, Porfirio Rubirosa had begun his lifetime of wandering.