This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

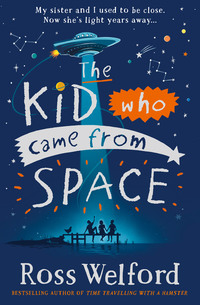

Read the book: «The Kid Who Came From Space»

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2020

Published in this ebook edition in 2020

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

Text copyright © Ross Welford 2020

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Cover illustration copyright © Tom Clohosy Cole

Ross Welford asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of the work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008333782

Ebook Edition © January 2020 ISBN: 9780008333799

Version: 2019-12-24

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Part One

Chapter One: Hellyann

Chapter Two: Ethan

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Four Days Earlier

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Part Two: Hellyann’s Story

Chapter Fifteen: Hellyann

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-one

Chapter Twenty-two

Chapter Twenty-three

Chapter Twenty-four

Chapter Twenty-five

Chapter Twenty-six

Chapter Twenty-seven

Chapter Twenty-eight

Part Three

Chapter Twenty-nine: Ethan

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-one

Chapter Thirty-two

Chapter Thirty-three

Chapter Thirty-four

Chapter Thirty-five

Chapter Thirty-six

Chapter Thirty-seven

Chapter Thirty-eight

Chapter Thirty-nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-one

Chapter Forty-two

Chapter Forty-three

Chapter Forty-four

Chapter Forty-five

Chapter Forty-six

Chapter Forty-seven

Chapter Forty-eight

Chapter Forty-nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-one

Chapter Fifty-two

Chapter Fifty-three: Hellyann

Chapter Fifty-four: Ethan

Chapter Fifty-five

Chapter Fifty-six

Part Four

Chapter Fifty-seven

Chapter Fifty-eight

Chapter Fifty-nine

Chapter Sixty: Hellyann

Chapter Sixty-one: Ethan

Chapter Sixty-two

Chapter Sixty-three

Chapter Sixty-four

Chapter Sixty-five

Chapter Sixty-six

Chapter Sixty-seven

Chapter Sixty-eight

Chapter Sixty-nine

Chapter Seventy

Chapter Seventy-one

Chapter Seventy-two

Chapter Seventy-three

Chapter Seventy-four

Chapter Seventy-five

Chapter Seventy-six

Chapter Seventy-seven

Chapter Seventy-eight

Chapter Seventy-nine

Acknowledgements

Keep Reading …

Books by Ross Welford

About the Publisher

SEARCH CONTINUES FOR MISSING TWELVE-YEAR-OLD

KIELDER, NORTHUMBERLAND

27 DECEMBER

Northumbria Police are seeking the public’s help to find a twelve-year-old girl missing from Kielder Village, Northumberland, since Christmas Eve.

Tamara ‘Tammy’ Tait was last seen leaving her home near the Stargazer public house on a bicycle at around 6pm on 24 December.

She is described as white, around 160 cm tall, of medium build, with blonde hair and brown eyes. She was last seen wearing blue jeans and a red North Face branded puffer jacket.

Volunteer teams and police have spent two days searching the forests and moors surrounding the remote village near the border between England and Scotland.

Anyone who may have seen Tamara or has any information in relation to her current whereabouts is urged to contact the police.

If you have information for the police, contact Policelink on 13 14 11 or call CrimeStoppers on 1800 333 000.

I read the sign again, glowing in front of me:

Type of organism: human female

Origin: Earth

Age: about twelve years

This brand-new exhibit will be introduced to the wider Earth Zone exhibition when emotional stability has been achieved

I looked at the bedraggled creature, and I wanted to reach through the unseen barrier and hold its hand. (This was neither allowed nor possible: the barrier would have repelled me with a painful shock.)

Its hair …

All right. I must stop saying ‘it’. The sign says it is a female, and so it should be ‘her’ …

Her hair fell in tight twists. I should have liked to see it when it was clean. Her pale and hairless skin was dotted with darker spots (‘freckles’, they are called in her language). Her clothes were similar to those worn by the other humans in Earth Zone. She had trousers of a coarse-looking fabric and a thick-looking padded item of a lighter shade on top, while her feet were clad in big shoes fastened with looped cord.

Her face was dirty and streaked with tears, and her eyes shone wet and bloodshot. She had been weeping (this is normal – humans do it a lot), although the atomic-level mechanical medication that had been given to her had closed down a lot of her primary cognitive functions—

(Wait. Is this too complicated? Philip suggests I should write: ‘Her brain had been made slow by the drugs she had been given.’ And that is, I suppose, close enough. I shall let you decide.)

Despite this, there was a spark of life in her eyes. Perhaps the dosage was imperfectly calculated, or she had an ability to resist some of the medication.

Anyhow, she looked at me and I was struck by how very expressive human faces are.

She put her hand to her chest and for a brief moment I thought she was making the sign of the Hearters, but – obviously – she was not.

She looked at me intensely and said, ‘Ta-mee.’

Just that: those two syllables.

She did it again: ‘Ta-mee.’

I glanced over both of my shoulders, but nobody was watching as I held up my PG and recorded this bit. Communicating with the exhibits is not exactly prohibited, but nor is it encouraged.

Is that her name? I wondered.

I repeated the syllables she had said, although the sounds were hard for me to duplicate.

‘Ta-mee,’ I said.

She nodded her head and made a weird face, as though she wanted to laugh and cry at the same time, which I did not understand – and still do not, not fully. Human beings are strange.

I imitated her gesture, and said my name.

The human female tried to repeat it. It sounded nothing at all like my name. She tried again and got a little closer. I practised the sounds a couple of times, and then tried saying my name in a way she might be able to repeat.

‘Helly-ann,’ I said, and a slow smile formed on her mouth.

She blinked hard and said it back to me. I found myself smiling at her.

Then her smile faded and she said two more syllables. ‘Ee-fan.’

A voice came from a speaker next to the sign: ‘Your time is up. Move along. There is a queue of people behind you waiting to see the new exhibit. Do not take more than your allotted time. Next.’

The human watched me go, then she retreated to the back of her enclosure and sat on the ground as two new spectators filed forward.

Ta-mee, I said to myself as I passed the Assistant Advisor who stood at the edge of the exhibit room.

‘That is your third time here, I believe,’ the AA said. ‘And communicating with the exhibits as well? I have my eye on you.’

Except he did not say it aloud. He did not need to – he just looked at me hard and it was enough.

That is how it is done here. Everybody obeys the rules. Nobody gets out of line.

All the way back to my pod-home, I struggled to keep a straight face, when really I wanted to crumple up and cry. That, however, would immediately single me out as being different, for people here do not cry – or laugh, for that matter.

Instead I repeated her name in my head, over and over: Ta-mee. Ta-mee. Ta-mee.

I played back the recording on my PG of the bit when she said her name and something else.

What is Ee-fan? I wondered. That is what she said: Ee-fan.

Perhaps, one day, I will find out.

Because I will be returning Tammy to Earth.

It will be dangerous. If I fail I will be put to sleep for the rest of my life.

And if I succeed? Well, I will probably have to do it again, with another exhibit.

Such is the curse of having feelings.

My twin sister Tammy has been missing for four days now, so when the doorbell goes, I assume it’s the police, or another journalist.

‘I’ll get it,’ I say to Mam and Dad.

Gran is asleep in her tracksuit on the big chair by the Christmas tree, her head back and her mouth open. The lights on the tree haven’t been switched on for days.

I open the door and Ignatius Fox-Templeton – Iggy for short and for slightly less weird – stands there wearing a thick coat, a flat cap and shorts (despite the snow). He’s holding a fishing rod in one hand and Suzy, his pet chicken, under his other arm. A large bag is slung over his back and his rusty old bike lies next to him on the ground.

For a moment we just stand there, staring at each other. It’s not like we’re best friends or anything. We had this sort of awkward encounter when Tammy first went missing on Christmas Eve. (I nearly broke his mum’s fingers with the piano lid, but she was OK about it.)

‘I, erm … I just thought … I was wondering, you know, if … erm …’ Iggy’s not normally like this, but he’s not normally normal anyway, and besides, nothing’s normal at the moment.

‘Who is it?’ calls Mam from inside, wearily.

‘Don’t worry, Mam. Doesn’t matter!’ I call back.

Mam has been getting worse in the last day or two. None of us has been sleeping well, but I’ve begun to think that Mam has not been sleeping at all. She’s got these blue-grey patches under her eyes, like smudged make-up. Meanwhile, Dad has been trying to keep busy at the pub and coordinating search efforts, but he is running out of things to do. Everyone wants to help us, which means the only thing left for us to do is to sit around and worry more, and cry. Sandra, the police Family Liaison Officer who has been here a lot, says that it is ‘to be expected’.

I turn back to Iggy on the doorstep.

‘What do you want?’ I say, and it comes out blunter than I intended.

‘Do you … erm, do you want to go fishing?’ he almost whispers. His eyes blink rapidly behind his thick glasses.

In case you don’t quite get just how odd I find this, you have to know that for the last few days the only world I have known has been one of worry and tears; and police officers being brisk; and journalists with cameras and notebooks wanting interviews; and people from the village bringing food even though the pub has a massive kitchen (we now have two shepherd’s pies and a huge pavlova); and Sandra, Dad and Mam trying to manage all of this with Gran; and Aunty Annikka and Uncle Jan flying in yesterday from Finland because … well, I don’t really know why. To ‘comfort’ us, I suppose.

All because, four days ago, Tammy vanished off the face of the earth. Nothing has been right since.

So when Iggy turns up wanting to go fishing, my first thought is: Are you mad? Then it dawns on me.

‘Is this Sandra’s idea?’ I ask, holding the front door half closed to keep the cold out.

Iggy doesn’t seem to mind. He gives his characteristic confident nod. Iggy knows Sandra already: he’s had several reasons for a police Family Liaison Officer to call at his house.

‘Yes. She thought you might want to get out of the house for a bit. You know, change of scene, and all that malarkey. Think of something else.’

Malarkey. It’s a very Iggy sort of word. He doesn’t have much of a local accent, though he’s not exactly posh either. It’s like he can’t quite decide how his voice should be and uses odd words to fill the gaps.

He goes on: ‘And so, here I am!’ He holds up his fishing rod. ‘Well,’ he adds, nodding to Suzy. ‘Here we are.’

I’m really not sure about Iggy. Dad doesn’t like him at all, ever since – soon after we arrived in the village – Dad caught him stealing a box of crisps from the pub’s outhouse. His mum said the outhouse should have been locked, so Dad’s not keen on his mum either. She keeps bees. She’s divorced from Iggy’s dad, I think.

Still, I have to admit: what Iggy is doing is quite kind, even if it wasn’t his idea. I don’t even like fishing. Suzy, Iggy’s chicken, stretches out her neck for a scratch, and I oblige, burying my fingers deep in her warm throat-feathers. To be honest, I have my doubts about Suzy too. I mean, who has a pet chicken?

Then, as I tickle Suzy, I think: What’s the worst that could happen?

So I put my head round the living-room door. Dad has gone into the kitchen on his phone and Mam is just staring blankly at the television, which is switched off. Gran snores a bit. The room’s far too hot and the remnants of the fire in the wood burner glow white-orange.

‘I’m just going out for a bit, Mam,’ I say. ‘You know – fresh air, an’ that.’

She nods but I’m not sure she completely heard me. All that’s in her mind is Tammy.

Tammy, my twin sister, who has disappeared off the face of the earth.

The tape is still there – POLICE LINE DO NOT CROSS – strung across the path where Tammy left her bike, but the police have searched the narrow lakeshore and the path a few times and there’s nobody there now. I haven’t been back since Christmas Eve, when it all happened, and I feel a tightening in my chest as we approach.

‘Are you all right with this?’ asks Iggy. ‘I’m sorry – I didn’t think about, you know … the lake and whatnot …’

‘Thanks. I’m OK.’ There is another approach to the waterside but it’s quite a bit further away.

We leave our bikes at the top of the path and go down the steep path through the woods, and all the while I’m thinking: This is where Tammy came …

We emerge on to the little shoreline. Iggy has been babbling on about a huge pike that lives near the Bakethin Weir, where the reservoir narrows into a sort of overflow lake.

‘When the weather’s really cold, pike often come to slightly shallower water … Using a laser lure is sure to attract him … this line has an eighty-pound breaking strain …’

It might as well be a foreign language to me, but I go along with it because it’s good to be able to think of something other than Tammy just for a while.

It’s mid-afternoon. Already the sky is darkening and the vast stillness of Kielder Water – a deep lilac colour in the near twilight – stretches out in front of us. I gasp at the sight and say, ‘Wow!’ very quietly.

Iggy comes up and stands next to me, staring out across the reservoir.

‘D’you reckon she’s still alive, Tait?’

Oof! His directness kind of throws me, and I feel the pricklings of annoyance until I realise he’s just asking what everybody else wants to ask. Everybody else tiptoes around the subject, very often scared to say anything in case they say the wrong thing.

I sigh. No one has asked me this before, so I even surprise myself with how certain I am. ‘Yup,’ I say. ‘I feel it. Here.’ I touch my chest near my heart. ‘It’s a twin thing.’

Iggy pouts and nods slowly as if he understands, but I don’t think you can unless you’re a twin.

‘Shh,’ I say. ‘Listen.’

I’m hoping that I might hear the whining noise from the night that Tammy disappeared. But the only sounds are tiny waves rippling on to the shore every few seconds and the rhythmic bump, bump of a bright orange fibreglass canoe hitting the long wooden jetty that sticks out over the water. The old planks of the jetty creak under our weight and Iggy unpacks his tackle bag.

The last time I stood on this jetty, I think, was with Tammy, playing our throwing-stones game. It’s basically: who can throw a stone furthest into the lake? But we’ve got rules, like size of stone, best-of-five and so on. Maddeningly, she nearly always wins. She’s good at throwing. Iggy is chuntering on …

‘Here we go. Two eight-strand braided fishing lines, one hundred metres, each with a steel wire trace … Four ten-centimetre shark hooks … one short rod and my good old pike reel, plus a Johnson Laser Lure.’

Iggy – who has a school record that you’d call ‘inconsistent’ – would get an A-star in fishing-tackle speak. From his bag he extracts something that he unwraps from its plastic and holds in front of me. I nearly gag at the smell.

‘What the …?’

‘It’s chicken. It was in the bin behind your pub.’ He adds quickly, ‘And if it’s in a bin it’s not stealing, is it?’

He had explained the plan on the way here, but now – kneeling on the jetty screwing his four-part rod together – he goes over it again.

‘So, this chicken breast is the bait. We paddle out about thirty metres and drop the chicken over the side attached to the buoy.’ He points to a red buoy the size of a football in the bottom of the canoe. ‘That should stop it sinking. It’s attached to the line and my rod. We paddle back, letting out the line, and just wait. Pikey comes along and sniffs the lovely meat …’

Iggy acts this out, his eyes narrowing as he twitches his nose left and right.

‘He just can’t resist it! Bam! Down go his jaws and he’s hooked. We see the buoy bobbing and start reeling him in to the jetty, where you are ready with your phone to get the pictures. Then we release him and we cycle back to fame and fortune, or at the very least, our pictures in The Hexham Courant!’

I keep telling myself that everything will be fine, even as we throw all of the gear into the canoe and I step into the rocking vessel, with the freezing water in the bottom seeping into my trainers. Suzy follows us and I could swear she looks at me funny. She takes one sniff of the rotten chicken and moves as far away as she can, right up to the far end of the canoe.

I hadn’t mentioned anything to Mam about going out on the water, because I hadn’t known till Iggy said so. My conscience is clear. But still …

‘Iggy?’ I say. ‘Do we … erm, do we have life jackets?’ I feel daft saying it, and even dafter when I see the look of disdain on Iggy’s face. ‘Doesn’t matter,’ I say. ‘I can swim.’

We unhook the wobbling canoe from the jetty and start paddling out towards the middle of the lake, saying nothing.

Perhaps it’s the motion of the canoe, but I begin to feel a bit queasy. The chicken (the dead one) isn’t helping. The putrid smell is on my hands from where I tossed it over the side attached to the red buoy.

I lean over and dip my hands in the icy water to wash them, then jerk back with a yelp, rocking the canoe.

‘Hey! Watch it!’ protests Iggy.

Did I imagine it?

I did imagine it. I look again: it’s just a log, submerged below the surface. There’s a branch coming off it that sort of looks like an arm, and in my head the whole thing became a floating body and I thought it was Tammy, and it wasn’t. It was just a log, and my mind playing tricks on me.

‘Shall we go back now?’ I say, trying to keep the tension out of my voice.

We paddle back, letting out the thick line as we go.

And so we wait on the jetty. And wait. I look up at the sky, which is much darker now, and I think I should be going back.

My phone’s clock tells me that we have been here for more than an hour, and frankly, I am bored, cold and still a bit shaken by the log-that-was-just-a-log.

And then the buoy moves.

‘Did you see …’

‘Yup.’

We scramble to our feet and stare out over the lake to where the buoy is once again still, with tiny ripples expanding from it.

‘What do you think?’ I say, but Iggy just takes off his cap and runs his fingers thoughtfully through his messed-up red hair, looking at the water.

We stay like that for several minutes then he says, ‘I think we need to check’ and he starts to reel in the line. ‘Perhaps the bait’s been taken, or fallen off. Dammit.’ The line is jammed. ‘Might have got caught on weeds, or a log.’

The more he tugs, the tighter it gets. ‘Come on,’ he moans, getting into the canoe. ‘We’ll have to free it.’

‘We?’ I murmur, but I get in anyway.

Iggy whistles to Suzy, just like you would to a dog, and she hops in obediently after us. Iggy pulls his cap down purposefully, pushes his glasses up his nose, and we begin to paddle back out towards the bobbing buoy.

Before we reach it, the massive splash comes.

It’s huge – like a car has been dropped into the water from a great height over on the other side of the reservoir.

Obviously, it isn’t a car. But – equally obviously – I don’t think it’s an invisible spaceship either, because I’m not completely mad.

But that is what it turns out to be.

The free sample has ended.