This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

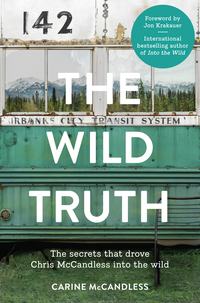

Read the book: «The Wild Truth: The secrets that drove Chris McCandless into the wild»

COPYRIGHT

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 77–85 Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

and HarperElement are trademarks of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

and HarperElement are trademarks of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

First published in the US by HarperOne 2014

This UK edition published by HarperElement 2014

© Carine McCandless 2014

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

All photos are from the author’s collection, with the exception of insert image 18, image 19, image 20, image 37 and image 38 © Dominic Peters; image 22 © Jon Krakauer.

Material quoted on p. vii from All Said and Done © Simone de Beauvoir; p. 15, “I Go Back to May 1937” © Sharon Olds; p. ix, “Dying in the Wild” © The New York Times; p. 107, Growing Wings © Kristen Jongen; p. 187, Doctor Zhivago © Boris Pasternak.

While every effort has beenv made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein and secure permissions, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any future edition of this book.

Carine McCandless asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out more about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780007585137

Ebook Edition © November 2014 ISBN: 9780007585144

Version: 2014-10-28

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

Prologue

Part One: Worth

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Part Two: Strength

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Part Three: Unconditional Love

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part Four: Truth

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Picture Section

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Afterword

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

For Chris

EPIGRAPH

I tore myself away from the safe comfort of certainties through my love for truth; and truth rewarded me.

—Simone de Beauvoir, All Said and Done

FOREWORD

On September 14, 1992, I got a phone call from Mark Bryant, the editor of Outside magazine, who sounded unusually animated. Skipping the small talk, he told me about a snippet he’d just read in the New York Times that he couldn’t stop thinking about:

DYING IN THE WILD, A HIKER RECORDED THE TERROR

Last Sunday a young hiker, stranded by an injury, was found dead at a remote camp in the Alaskan interior. No one is yet certain who he was. But his diary and two notes found at the camp tell a wrenching story of his desperate and progressively futile efforts to survive.

The diary indicates that the man, believed to be an American in his late 20’s or early 30’s, might have been injured in a fall and that he was then stranded at the camp for more than three months. It tells how he tried to save himself by hunting game and eating wild plants while nonetheless getting weaker.

One of his two notes is a plea for help, addressed to anyone who might come upon the camp while the hiker searched the surrounding area for food. The second note bids the world goodbye.

An autopsy at the state coroner’s office in Fairbanks this week found that the man had died of starvation, probably in late July. The authorities discovered among the man’s possessions a name that they believe is his. But they have so far been unable to confirm his identity and, until they do, have declined to disclose the name.

Although the article raised more questions than it answered, Bryant’s interest had been piqued by its handful of poignant details. He wondered if I’d be willing to investigate the tragedy, write a substantial piece about it for Outside, and complete it quickly. I was already behind schedule on other writing assignments and feeling stressed. Committing to yet another project—a challenging one, on a tight deadline—would add considerably to that stress. But the story resonated on a deeply personal level for me. I agreed to put my other projects on hold and look into it.

The deceased hiker turned out to be twenty-four-year-old Christopher McCandless, who’d grown up in a Washington, D.C., suburb and graduated from Emory University with honors. It quickly became apparent that walking alone into the Alaskan wilderness with minimal food and gear had been a very deliberate act—the culmination of a serious quest Chris had been planning for a long time. He wanted to test his inner resources in a meaningful way, without a safety net, in order to gain a better perspective on such weighty matters as authenticity, purpose, and his place in the world.

Eager to receive whatever insights into Chris’s personality his family might be able to provide, in October 1992 I mailed a letter to Dennis Burnett, the McCandlesses’ attorney, in which I explained,

When I was 23 (I’m 38 at present) I, too, set off alone into the Alaskan wilderness for an extended sojourn that baffled and frightened many of my friends and family (I was seeking challenge, I suppose, and some sort of inner peace, and answers to Big Questions) so I identify with Chris to a great extent, and feel like I might know something about why he felt compelled to test himself in such a wild and unforgiving piece of country. . . . If any of the McCandless family would be willing to chat with me I’d be extremely grateful.

My letter resulted in an invitation from Chris’s parents, Walt and Billie McCandless, to visit them at their home in Chesapeake Beach, Maryland. When I showed up on their doorstep a few days later, the intensity of their grief staggered me, but they graciously answered all of my many questions.

The last time Walt or Billie had seen Chris or spoken to him was May 12, 1990, when they’d driven down to Atlanta to attend his graduation from Emory. Following the ceremony, he mentioned that he would probably spend that summer traveling, and then enroll in law school. Five weeks later, he mailed his parents a copy of his final grades, accompanied by a note thanking them for some graduation gifts. “Not much else is happening, but it’s starting to get real hot and humid down here,” he wrote at the end of the missive. “Say Hi to everyone for me.” It was the last anyone in the McCandless family would ever hear from him.

Walt and Billie were desperate to learn everything they could about Chris’s activities from the moment he performed his vanishing act until his emaciated remains were discovered in Alaska twenty-seven months later. Where had he traveled and whom had he met? What had he been thinking? What had he been feeling? Hoping that I might be able to find answers to such questions, they allowed me to examine all the documents and photos that had been recovered after his death. They also urged me to track down anyone he’d met whom I could locate from these materials, and to interview individuals who were important to Chris before his disappearance—especially his twenty-one-year-old sister, Carine, with whom he had had an uncommonly close bond.

When I phoned Carine, she was wary, but she talked to me for twenty minutes or so and provided important information for the 8,400-word article about Chris, titled “Death of an Innocent,” published as the cover story in the January 1993 issue of Outside. Although it was well received, the article left me feeling unsatisfied. In order to meet my deadline, I had to deliver it to the magazine before I’d had time to investigate some tantalizing leads. Important aspects of the mystery remained hazy, including the cause of Chris’s death and his reasons for so assiduously avoiding contact with his family after he departed Atlanta in the summer of 1990. I spent the next year conducting further research to fill in these and other blanks in order to write a book, which was published in 1996 as Into the Wild.

By the time I began doing research for the book, it was obvious to me that Carine understood Chris better than anyone, perhaps even better than Chris had understood himself. So I phoned her again to ask if she would talk to me at greater length. Highly protective of her absent brother, she remained skeptical but agreed to let me interview her for a couple of hours at her home near Virginia Beach. After we started to talk, Carine determined there was a lot she wanted to tell me, and the allotted two hours stretched into the next day. At some point she decided she could trust me, and asked me to read some excruciatingly candid letters Chris had written to her—letters she had never shown to anyone, not even her husband or closest friends. As I began to read them I was filled with both sadness and admiration for Chris and Carine. The letters were sometimes harrowing, but they left little doubt about what drove him to sever all ties with his family. When I eventually got on a plane to fly home to Seattle, my head was spinning.

Before Carine shared the letters with me, she asked me not to include anything from them in my book. I promised to abide by her wishes. It’s not uncommon for sources to ask journalists to treat certain pieces of information as confidential or “off the record,” and I’d agreed to such requests on several previous occasions. In this instance, my willingness to do so was bolstered by the fact that I shared Carine’s desire to avoid causing undue pain to Walt, Billie, and Carine’s siblings from Walt’s first marriage. I thought, moreover, that I could convey what I’d learned from the letters obliquely, between the lines, without violating Carine’s trust. I was confident I could provide enough indirect clues for readers to understand that, to no small degree, Chris’s seemingly inexplicable behavior during the final years of his life was in fact explained by the volatile dynamics of the McCandless family while he was growing up.

Many readers did understand this, as it turned out. But many did not. A lot of people came away from reading Into the Wild without grasping why Chris did what he did. Lacking explicit facts, they concluded that he was merely self-absorbed, unforgivably cruel to his parents, mentally ill, suicidal, and/or witless.

These mistaken assumptions troubled Carine. Two decades after her brother’s death, she decided it was time to tell Chris’s entire story, plainly and directly, without concealing any of the heartbreaking particulars. She belatedly recognized that even the most toxic secrets could possibly be robbed of their power to hurt by dragging them out of the shadows and exposing them to the light of day.

Thus did she come to write The Wild Truth, the courageous book you now hold in your hands.

Jon Krakauer

April 2014

PROLOGUE

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

—George Santayana, The Life of Reason: Reason in Common Sense

THE HOUSE ON WILLET DRIVE looks smaller than I remember. Mom kept the yard much nicer than this, but the haunting appearance of overgrown weeds and neglected shrubs seems more appropriate. Color returns to my knuckles as I release the steering wheel. I hate this fucking house. For twenty-three years I managed to steel myself while passing these familiar exits of Virginia’s highways. Several times I wrestled with the temptation to veer off, wanting to generate memories of time spent with the brother I miss so terribly. But pain is a cruel thief of childhood sentiment. People think they understand our story because they know how his ended, but they don’t know how it all began.

Once a carefully tended mask, the house’s facade now appears to have been abandoned. Unruly thickets of sharp holly stab at the foundation, their berries like droplets of blood drawn from its bricks. The wood siding sags, forgotten and pale, lifeless aside from the mildew creeping across its seams. Gone are the manicured flower beds; the front yard is now adorned with random papers and bottles from passersby. It’s as if the dwelling has utterly expired, worn out from too many years as the lead in a grueling play.

The knot in my stomach quickly transforms into nausea, and I scramble out into the crisp October air to hunch over and wait, patiently. But the relief doesn’t come.

The concrete driveway lies vacant, broken and stained. But I realize the house is not deserted. Someone had to roll the trash cans to the street, and a neatly covered Harley is tucked under the carport, a single wheel exposed just enough to be identified.

I stagger back to my Honda Pilot and crawl inside to make my escape. But just before my key strikes the ignition, a large Chevy pickup flashes in my rearview mirror and lumbers up the driveway. A woman steps out of the truck and begins to unload a few items from the cab. As she suspiciously eyes my SUV parked in front of her house, I rebuke myself for not parking on the opposite side of the street. With a few encouraging breaths and a burst of energy, I find myself back at the bottom of the long, sloped driveway. Her expression asks what the hell I am doing there.

“Hello, ma’am? My name is Carine McCandless. I grew up in this house.” I watch her furrowed brow soften into acknowledgment. “Do you know the history?”

“Yes. Well, a little,” she wavers.

I hastily assume her next reply as I walk up the incline. “May I come up to talk to you?”

She puts down her purse and packages on the truck bed and shakes the hand I have offered. “Marian.”

Marian is tall, nice looking, with a strong build and sturdy handshake. Her long strawberry-blond hair reminds me of Wynonna Judd, and her bright pretty blouse and casual black pantsuit are what you might expect to see on an underpaid social worker. Amongst the delicate necklaces around her neck hangs a heavier chain with a distinctive silver and black Harley Davidson emblem. Her expression is warm yet tentative.

I press on. “I was hoping you wouldn’t mind if I looked around a little bit?”

She gestures at her disheveled yard and balks. “Well, I don’t know what you would gain from that. It certainly doesn’t look the same as it did when you lived here.”

There is a long pause, and it remains unspoken, yet obvious, that Marian is not prone to welcome visitors. Eventually she looks back at my hopeful face and relents. “Well, you’re gonna have to give me a minute to let my dog out before he pees all over the house.” She smiles and hoots, “He’s an ole boy, that Charlie!”

As we walk around the backyard, the wiry chocolate Labrador keeps his head low while he examines me through the tops of his eyes. Harmless growls emerge from his graying muzzle like the rumblings of an old man disturbed from his routine. While urinating about the yard, Charlie ensures that either I am securely entangled in his extensive leash or he is standing between the house and me. Marian ignores the gaps in the dilapidated fence, apologizing as she liberates my legs again and again. “Charlie could just jump right over that.”

While I struggle to maintain my balance, I scan the areas where Chris and I would seek our refuge. No evidence remains of the massive vegetable garden we picked beans in every summer. Aster and chrysanthemum no longer grace the fallen leaves. The beautifully landscaped beds that Mom had so carefully lined with large stones now appear as mouths agape with crooked teeth, coughing up snarled knots of condemned shrubs and weeds. The railroad ties that had been systematically placed to create steps between the multilevel beds are barely defining the slope of the yard.

Free for the moment from Marian’s canine guardian, I make my way to the higher level of the backyard. In the left corner is a generous slope where Chris and I imagined ourselves as archaeologists and where he refined his considerable storytelling skills as an adolescent.

Our neighborhood was developed among a complex grouping of small hills and valleys where minor rivers had meandered centuries earlier to service tobacco plantations. The houses on our street were built along a strand of dehydrated streambeds. Looking down the back rows of neighbors’ chain-link fences, I can still trace the forgotten path of running waters. And those waters left behind a great deal of storytelling material.

I tell Marian how Chris and I would haul up our wagon full of plastic shovels and buckets—and the occasional soup spoon swiped from the silverware drawer—to dig section by section, getting filthy, eager to discover relics of the past. We didn’t come across anything that would be of significance to anyone else. But to Chris, everything we unearthed was legendary. Some of our greatest finds became our secret collection. Between the effortless detection of widespread oyster shells, we were thrilled whenever the excavation revealed ceramic shards of glazed white china. Arms raised in victory, we would run down to the spigot and wash off the mud and dirt until we could see a pattern we had come to recognize: depictions of oriental houses in soft blue-violet hues. Then we would sift through the shoe box in which we stashed our trove, looking to match the remnants together like puzzle pieces.

Our proudest days were those when our score completed an entire plate. Then we would sit and relish our accomplishment, gazing back up at the dig site while Chris weaved intricate stories about how the pieces had come to rest there. He told of ancient Chinese armies—the soldiers coming under surprise attack while enjoying meals in their dining tents—defenseless against superior forces while their dinner plates shattered and fell beside them, only to be discovered years later by the fantastic archaeological duo Sir Flash and his little sister, Princess Woo Bear.

Our dig site now lay covered with scattered piles of yard debris. The pleasant scent of late-season honeysuckle drifts over from the yard next door, and I recall hopping the fence like scavengers to suck the nectar from its delicate summer blooms.

On the days when our instincts led us to flee to greater distances, Chris would take me running down Braeburn Drive to Rutherford Park, where active streams could still be found. We ventured along the creek beds, soaking our sneakers with failed attempts to jump across the clear, cold rush at wider and wider points, skipping rocks, singing Beatles songs, and reenacting scenes from our favorite television shows. Chris was brilliant at creating diversions, and nature was always his first choice of backdrop. And even if the chosen scene from Star Trek, Buck Rogers, or Battlestar Galactica didn’t call for heroics, in my mind he was always my protector.

A lush blanket of English ivy covers most of the remainder of the yard’s top level. The plant’s deep green leaves were once contained behind yet another stone boundary, established and maintained as a neat and tidy latrine for our Shetland sheepdog, whom we loved to play with for hours on end. If Chris was captain of our adventures, Buck—or as he was officially registered by Mom on his AKC papers, Lord Buckley of Naripa III—was his first lieutenant. A little soldier with a big attitude, Buck regularly defeated our mother’s efforts to grow a thick lawn by tearing up tufts of grass while nipping at our heels, his herding instincts driving him to run circles around Chris and me.

Ready now to swap stories, Marian explains that she bought the house from my parents two decades ago, as a new beginning for herself and her young sons after their home had burned down. I was unaware that it had been that many years since my parents had sold it, and that the house had not changed owners since. Marian didn’t give many details about the boys’ father, but from what she did allow, about her long work hours and single income having made it difficult to keep up with the house, I gathered that going it alone was a tough but necessary decision she had accepted without hesitation. She speaks endearingly about her sons still coming by for visits, helping with things around the house when they can, and the future projects they have planned. Her face lights up when the subject turns to travel. She tells me of her solo trips aboard her Harley on any given day when nice weather coincides with a rare day off work. When I respond with my own history of solo hikes in the Shenandoah and my Kawasaki EX500, she is gracious enough to not knock me for having owned a crotch rocket.

With a nudge and a yelp, Charlie informs Marian that he is done, and I am surprised when she invites me to follow them inside.

AS I STEP INTO MARIAN’S KITCHEN, the odor of spent nicotine overwhelms me before the storm door closes. Fighting my allergy to the smoke and my urge to retreat, I fail to cough discreetly.

“Oh! My goodness! Do you need some water?” Marian kindly offers.

I glance at the eruption of glass and stoneware that flows from the kitchen sink onto the countertop, clean but chaotic. “No—no, thank you. I’m fine.” I suppose the conditions outside the house should have prepared me for what might lie within. Still, I am humbled that Marian has invited me into her home. Her smile is comfortable and enticing, and even Charlie yips and spins in his excitement to begin the tour.

“Excuse the mess,” she apologizes as she leans against the table. “I’ve just been so incredibly busy!” The excessive piles of paper and mail have been carefully organized, leading me to believe that she has a specific identity for each stack. Ashtrays occupy every horizontal surface. Almost everything around me, aside from the clutter, appears just as it did when I stood here as a child: the layout, the cabinets, the counters and backsplash, even the appliances are the same.

“I remember making drop cookies on this stove with my friend Denise,” I reminisce.

Marian seems pleased as I travel back in time. I recall a photo of Buck and me sprawled on this floor, fast asleep, taken on the first day we brought him home. Nestled in my yellow sweatshirt, he was just a puppy. I was in pigtails.

Marian takes me across the main floor of the split-level house. The blue floral wallpaper I remember from childhood has been replaced with a coat of adobe beige and Navajo sandpaintings. We continue down two flights of stairs to the basement, where my parents kept their office. This is where Mom spent most of her time—often in pajamas, a down vest, and slippers—hard and fast to the day’s work as soon as she was awake. She had traded her own career aspirations for the promise of a brighter future by helping Dad start User Systems, Incorporated, an aerospace engineering and consulting firm specializing in airborne and space-based radar design. The long hours they put in made them wealthy. But not happy.

Mom was constantly typing and editing documents, making copies, preparing and binding presentations. Before we left for school, she was on her fourth cup of coffee. In addition to her office work, she was obligated to do infinite loads of laundry, keep the house spotless, maintain a beautiful yard, and serve dinner punctually. By the time Chris and I returned home from sports practice and band rehearsals, she had replaced the pots of java with bottles of red wine, to begin numbing herself before Dad got home. During the workday he was meeting with prestigious scientists at NASA; acquiring contracts with companies like the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Northrop Grumman, and Lockheed Martin; or giving lectures at the Naval Academy.

Sometimes, if Dad was away on an extended trip, we were blessed with a few days of calm. Most days, though, as soon as we heard his Cadillac pull into the carport, Chris and I ran and hid. He yelled out names and barked orders as soon as he opened the front door. He often complained to our mother that she should be fully dressed for his arrival: short skirt, three-inch heels, hair and makeup immaculate.

Chris and I did plenty of chores and became more useful as we got older, but Mom’s workload was copious and challenging. She eventually reined in her “I can do it all” determination and hired a part-time maid to help with the housework. This resulted in the boss telling her she was getting lazy and now had no excuse not to fulfill the sexy secretary role.

In actuality, she played an equally important role in their business. He never acknowledged how valuable she was to their company, but his awareness of it is likely why he constantly bullied her. “You’re nothing without me, woman!” he would scream at any indication of her insurgence. “You have no college education! I’m a fucking genius! I put the first American spacecraft on the moon! You’ve never done anything important!”

If our mom had been willing to rely on her own resourcefulness, she could have accomplished just about anything—even mutiny. Regardless of his scientific degrees and expertise, our father stepped on her to attain each level of his success. I learned at a very young age how to identify a narcissistic, chauvinistic asshole and vowed that I would never put up with one. Just as soon as I was old enough to have a choice.

Mom always appeared beautiful and well composed on the evenings Dad brought home business associates for dinner. Chris and I were also expected to perform at our highest level. This usually included a piano, violin, or French horn recital, along with the touting of our most recent academic and athletic awards. I remember right before one such evening, when I was nine years old, lying at the foot of Mom’s desk, writhing in pain. There was so much movement inside my gut I thought my intestines might explode at any moment. “Shhhhh! Quiet!” Mom hissed. “I have to get this done before your father gets home!” She was half dressed, with curlers in her hair and dinner in the oven. When I expressed an opinion about the cause of my agony, she shouted, “I said be quiet, Carine! Go to your room and lie on your stomach! It’s probably just gas!” Fortunately, she was right about the gas. Unfortunately, I learned to just lie down and keep quiet.

Marian leads me back up one flight into what was our family room, where Chris and I demonstrated our architectural prowess with elaborate fort making. We stripped our beds and emptied our shelves, stacked books onto table corners to secure sheets for ceilings and blankets for walls. There wasn’t a pillow spared; we needed them all for hallways and doors. Sometimes Mom and Dad would let us sleep inside the fort overnight. Chris carefully removed one precarious anchor and read to me by the glow of his camping lamp. There was usually popcorn involved closer to bedtime, especially if the television was being utilized as an interior fixture.

Today, next to a large couch sits a pedestal antique smoking stand. Traces of ammonia linger with the ashes. The carpeting has been pulled up, no doubt from too many times ole Charlie didn’t make it outside. The tack strips remain unattended along the edges of the baseboards.

“Watch your step,” Marian warns. “I’ve got to replace the carpet soon.” She dodges the rows of sharp nails as she leads me down the hallway to a bedroom and half bath. “I just use this room for storage now,” she says as she opens the door, and I take a quick peek at what was my bedroom for a short stint as an emerging teenager.

“You still get camel crickets?” I ask.

“Whoa, do I!” exclaims Marian, and we exchange a wince of revulsion.

The fact that our house was always neat and clean did not keep these nasty insects from invading the half-sunken ground floor and basement below. What appeared to be the result of a demonic union between a spider and a common field cricket, these fearless creatures blended perfectly with the plush brown carpeting and attacked—rather than avoided—any larger moving target. Every morning I had to hunt and kill four to five of these disgusting bastards before I could safely get ready for school.

Marian and I continue to the sizable laundry room, which served as another avenue to flee outdoors. I am once more amazed by the muscle of seventies-era appliances when she points out the same washer and dryer that Mom taught me to use. A new fridge sits where our deep freezer held extra meats for Mom’s dinners and extra bottles of Dad’s gin.

As we walk back through the hall, we pass a closet that provided access to a crawl space beneath the stairs. Chris and I used to hide in there, I think, and I am completely unaware that I’ve said it out loud until I notice the disquieted expression on Marian’s face.

The free sample has ended.