This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

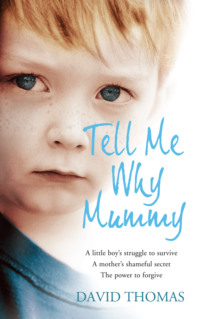

Read the book: «Tell Me Why, Mummy: A Little Boy’s Struggle to Survive. A Mother’s Shameful Secret. The Power to Forgive.»

Tell Me Why, Mummy

A little boy’s struggle to survive A mother’s shameful secret

DAVID THOMAS

Dedication

To my children Molly, Nathan, and Danielle who have shown me the greatest pleasure of all is being a parent

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Part 1: The Chosen One

Chapter One: Living In The Shadows

Chapter Two: My Dark Mummy

Chapter Three: A Man Called Reg

Chapter Four: Smashing The Dream

Chapter Five: Easy Access

Chapter Six: Interlude

Chapter Seven: Fair Game

Part 2: Rage To Forget

Chapter Eight: Teenage Blues

Chapter Nine: Night-Runner

Chapter Ten: Loose Cannon

Chapter Eleven: Master Criminal

Chapter Twelve: On The Scrapheap

Part 3: Another Kind Of Memory

Chapter Thirteen: Into The Fire

Chapter Fourteen: Heartbreaker

Chapter Fifteen: Down Memory Lane

Chapter Sixteen: Sparks And Embers

Epilogue

Inspired by David's story?

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

I know she has been drinking again. I can hear her crashing around upstairs and then, suddenly, she’s in the kitchen. She can barely stand as she staggers through the door and gropes her way along the grubby kitchen cabinets, trying to get to me across the room.

I’m playing with my bricks on the lino floor. She starts tottering towards me, falls over, and then tries to lie down next to me. She is completely naked, her eyes glazed and unfocused as she emits a low drunken moan.

‘David,’ she says, her voice alternating between an inaudible moan and a loud drunken shout, ‘come over here.’

She doesn’t seem to realize that I am already close beside her. When she tells me to do something I always do it at once. I love to please her and I hate to displease her. If I don’t do as I’m told she may stop loving me. She won’t smack me or hurt me, but I think she will be angry. So I stand up and then sit down again, so that she can see that I am there, next to her.

When she sees me near her, she looks up and pulls me down towards her. She then takes my hand and places it between her legs, which are spread wide open. It feels strange and I don’t understand why she’s doing this. She rubs my hand up and down between her legs and starts to moan again. She is sighing and keeps moving my hand inside her and then – I don’t know why or how – I start to realize that the loud moaning noises are not, as I first thought, signs of distress but of pleasure.

As this dawns on me, and because she continues to moan, I take it that this game is good and so I’m happy to continue to do it as long as she wants to. She carries on rubbing herself with my hand for some time until she has had enough.

Then she pushes my hand away and without saying a word, my mother picks up her bottle and staggers back across the kitchen to make her way upstairs, while I go back to playing with my bricks on the lino floor.

PART 1

The Chosen One

1

Living in the Shadows

Most of the time you’re the best Mummy in the whole world. But then you change. You get angry and make me do things I don’t understand. Why do you want me to do those things? Please tell me why. Why can’t you make my dark Mummy go away? I’m afraid of her. Don’t you see what she does? Don’t you see what she makes me do? Why do you pretend you don’t know?

I am only five but I’ve already got so many questions I can feel them pressing on my heart. Sometimes it’s hard to breathe. There aren’t any answers, just more questions. I don’t know if I will ever have the answers. All I know is that my questions are piling up inside me. I try to bury them but there are too many. I feel like an unexploded mine.

* * *

The house in which I am born, on 6 April 1968, is in an idyllic setting: the small rural village of Calder Bridge, near Halifax in West Yorkshire. The village is picture-postcard perfect with beautiful cottages made from Yorkshire stone, a small village pub and post office, all wrapped up in the incredible rolling landscape of the Pennine Hills. I love the glorious countryside feel to it – the large wide-open spaces, the rolling fields, the luscious woodland, the sense of freedom. Even aged three or four, my mother lets me wander through the woods to play with other kids. Everyone knows everyone else and there’s a real sense of community.

Our house is quite isolated though. It stands in a fork in a country lane and is one of four terraced charcoal-grey-stone cottages, smothered at each end with dark-green ivy, surrounded by trees and perched above a steep ravine through which a sparkling river runs over mossy rocks and boulders. Although from the front of the building the cottages seem squat, with small, poky rooms where the light never spreads, the back of the building slopes steeply down towards the ravine. So there are only two floors on the front of the house, but two more floors at the back. They tower over the river, and even in summer the whole building is gloomy and mysterious like a gothic mansion.

My earliest memories are of these strange contrasts – the warm, cosy, intimate times when I play with my mother; the cold, isolated, dark, forbidding times when things are completely different – in my family life as well as in the places surrounding it.

Years ago, there was a cotton mill a hundred yards along the ravine and you can still see signs of it along the brick banks of the river. A hundred yards from my home, between where the mill used to be and the house, is an old scrap-metal yard which may very well be the most beautiful scrapyard in the world, as it virtually hangs over the river.

The scrapyard is a second home to me. I love looking up at all this wonderful metal piled up as far as I can see. It’s dirty and greasy, a perfect place for a small boy. I play hide and seek with the owner’s young son Jeff, in and around the stacks of rubber tyres, dustbins, stripped doors, racks of trellises, lead piping, stained and damaged cast-iron baths and wash basins, wrecked car parts, and all the other layers of junk that have settled one on top of the other like geological strata in this metal wonderland. Jeff’s father is gruff but kindly, a good-humoured, plain-speaking Yorkshireman who sometimes smiles but never says much to me.

When I’m not playing with Jeff, I play by myself or sometimes with George, a lad of my age who lives a few fields away, and whose mother gets on well with mine. My earliest memories are of forever playing outside. Although as a young child I am not very adventurous or physically courageous, I am naturally inquisitive and am always looking for birds and animals in the fields and fish in the river.

One day, playing in the scrapyard, I find a bird’s nest, embedded deep within some rusty metal boulders. Even as a four-year-old I am amazed at how tough, tenacious and adaptable life is; how such a vulnerable thing as a bird’s nest with its firm outer ring and its gentle cosy lining can find a home in this alien place; how life can grow and thrive here, in the shadows.

The next time I go to see the nest, the chicks have hatched. I stare at the broken shells in amazement. Only yesterday they were tiny fragile pear-shaped eggs with beautiful, delicate patterns. When I return later in the day all the shells have gone.

I ask the scrapyard owner what’s happened to them.

‘Mother’s eaten ’em, lad, or chucked ’em away,’ he says. ‘She likes to keeps things clean and tidy.’

‘I liked the eggs,’ I say.

‘Aye lad, but as they always say, you can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs.’

I think about this Omlet and wonder how many eggs you must break to make it. Are all the chicks baby Omlets and what happens to the mother Omlet? Do they all stay in the nest together or do they fly away and never see each other again?

I go down to the nest every day after that and look at the chicks.

One day when I go to the nest, I find it empty. I wonder what’s happened to the chicks and where they’ve gone. I think they must have all turned into Omlets and flown away.

Dad has a lock-up garage near the scrapyard where he stores something special. One day he shows me what he keeps inside: it’s a red Volvo P1800. I’m very excited as this is the car used by Simon Templar in the TV show The Saint. The Volvo is impossibly beautiful with swooping curves and looks very exotic – as good as any other car on the road. We also have a Rover called Bluebell which Dad keeps on a patch of grass on the side of the house. It’s a gorgeous car – the kind Jim Callaghan drives and Mum says he’s a very important man and one day he might even be Prime Minister.

My father, Keith, is a big man, a foot taller than my mother, with a large face, horn-rimmed glasses, short black hair combed back from his forehead and a thick black beard. He doesn’t have a moustache though, so when I’m older I think his beard looks like one of those joke beards you stick on your chin to make you look like a monkey or a rabbi.

He likes making jokes, my Dad, but in other ways he can be a bit of a cold fish – he’s not affectionate with me and there’s never any rough and tumble with him. He is genial and patient towards me but he’s also strict – firm but fair. Unlike my mother, he isn’t sociable or gregarious. He doesn’t smile a whole lot.

Dad works as a draughtsman but his true obsession is his motorbikes and engines. We have lots of space in the house and he even has a garage underneath the house just for his motorbikes, which he rides up and down the lane. He may not have built this garage himself but he’s changed it to make it the way he wants it to be. Down in the garage, I peer up at him in wonder as he takes apart the engine. He lets me watch and answers my questions.

‘What you doing, Dad?’

‘I’m just changing the oil in the gearbox.’

‘Why, Dad?’

‘To keep the gears all working nicely, son.’

‘How d’you do it?’

‘Well, you have to remove the drain plug from the gearbox, drain the oil, and then remove the gearbox fill plug and fill it with new oil. Then you wipe away any oil you’ve spilt so it’s all clean and replace the chassis protector . . . ’

And on he goes, carefully explaining what he’s doing. I don’t really understand what he’s saying though. After changing the oil, he’ll start on the nuts and bolts.

‘Can I help you, Dad?’

‘Yes, you can hand me that spanner, lad.’

‘What’s that for?’

‘Just to tighten the nuts around these bolts . . . look. But you mustn’t screw them too tight. Otherwise you’ll never be able to loosen them if you need to. Gently does it.’

I watch as he tightens the nuts, totally lost in what he’s doing. After that, he polishes all the chrome until it shines like the sun gleaming over the river.

The house we live in is one of a row of four. As the other three come up for sale Dad buys them all. The odd thing is, though, that I know some of the other houses are, or used to be, owned by my Mum’s family. Is my Dad getting richer while my Mum’s family are getting poorer? These things are mysteries to me. I may never know the truth.

Our house above the river is our little patch of heaven. We have no direct neighbours, but there’s a farmer up the road who stops and talks as he passes our house many times a day. Although we eventually own all four houses, the really strange thing is that we only live in one, which always feels dark inside. That’s because it’s overshadowed by trees and also because the rooms are small and the windows let in very little light.

The house is bare and simply furnished; the kitchen has very basic chipboard cupboards and lino on the floor. I’ve seen lino in other people’s kitchens so we’re not that different from other people, at least as far as that goes. But I think about the kitchen lino for another, much stranger reason.

* * *

My parents met through the Methodist Church. They were in the choir and, as my mother is always keen to point out, both were as innocent as young lambs when they married in 1966. But as far as I know, from the brief times I spend in George’s house with his family and then when I look at my Mum and Dad and me, I can already see that we don’t seem to work like a normal family – we never do things together. I spend time just with Dad and his cars and bikes, or I spend time just with Mum, who can be great fun when she wants to be.

Mum’s name before she was married to my Dad was Carol Stones and she was born in March 1945. There’s a photo of her as a little girl with her older brother Jim in a big dark wooden frame in the living room: she’s smiling straight at me, looking very sweet with a cheeky grin. Jim’s much taller, with darker hair. There are other photos of Mum: in one she’s holding her doll and looks like a mummy dolly holding her baby dolly – they’ve both got the same curly golden hair. In another photo her hair is much straighter, like pale straw, and she’s got plaits and is standing with other children in her class; in others she’s swimming in the sea; riding a donkey; walking with her dog; in yet another photo she looks like a fairy princess with a bunch of roses and silver crown – I think she’s a bridesmaid but I don’t know who the bride is.

In all these photos Mum has the same round face, chubby cheeks and mischievous look. As my Grandad, her dad, would say, ‘When she was a lass she was a smasher.’

There’s another photo in a lighter plastic frame. She’s older in this one and has turned into a strawberry-blonde teenager. She’s smiling at me again and her smile is warm and friendly. In another photo she’s a grown-up woman – I think she’s a bridesmaid again – and her hair is piled on top of her head with a light-blue ribbon the same colour as her dress and she’s wearing white shoes with pointed toes. There’s also a grey-looking photo of Mum in nurse’s uniform, only in this one she’s not smiling.

There are also photos of Mum and Dad’s wedding at the Methodist church. She’s all in white and he’s all in black. Her face is less plump in these pictures and she looks different – softer and more frail – but very happy. Dad’s grinning, like he’s just eaten the cherry on the cake.

There’s one other photo of Mum and Dad together that I love to look at. They’re at the zoo together and are both laughing like they’re having fun. Dad’s wearing his black shiny PVC Pacamac and has one arm round Mum. Tucked under his other arm is a tiny black monkey. Mum’s holding her free arm out. Perched on her elbow is a large parrot who’s gazing inquisitively at both of them. I like to think that they’ve had at least a few good times together.

Later, in my teenage years it dawns on me that when I was a child Mum was always slightly unkempt, never very well dressed; her hair a little scruffy; she wasn’t beautiful but she had good skin (and freckles) and was still attractive. By the time I turned up she had adopted a tight perm which she kept throughout her life. She never wore much make-up and, as she grew older, her dress sense seemed to disappear almost completely. But when she was happy, she had a great smile and an infectious laugh.

My mum was 23 when I was born. She never talks about her early childhood with her brother and parents, but occasionally mentions small things about her teenage years, such as how she once went on a motorbike with a boyfriend which she thought was very exciting.

As early as I can remember I visit other local houses with her and we often go for walks in the woods. She likes to show me all the flowers and we pick them together. She is warm and affectionate to me, and sociable to others. My dad is also sociable, though not in such a warm way. Mum has a good sense of humour – as long as she doesn’t feel she’s having the mickey taken out of her. She can never handle that very well.

Other people always respond to Mum. She can strike up a conversation with a lamp-post and has a way of getting people to talk about themselves quite quickly. They feel they can open up to her and she has a few solid, long-term friends. She will chat away for hours and hours about personal things – about people she knows and what’s happening in their life and their problems – and what she’s saying about them is as much a mystery to me as when Dad talks about his bikes and his engines.

But my mother’s life and personality are made up of two separate halves: she is two different people. She is loving, caring, affectionate and supportive, and can be funny, sympathetic and always keen to talk.

But she also has a dark side and when it surfaces it is a bad place to be – not just for her but also for me when I am with her. It’s not just bad, it’s dreadful. She turns into another person: nasty, spiteful, vindictive, malicious, uncaring, inconsiderate. Mummy normally never says bad words and thinks it’s dreadfully rude to fart or burp – but when she’s in the dreadful place she uses lots of bad words.

When I am very little the bad words themselves don’t mean anything to me, but the effect of them, and the way she hurls them at me – or at the walls and furniture as she slams and barges into them – is very, very frightening.

I sense this has a lot to do with my Mummy drinking because I’ve seen her drink a lot of foul-smelling liquid which I’ve found out is called brandy. She drinks it very, very quickly until she is almost asleep. Except that she’s not asleep. She’s still awake and that’s when she scares me.

The brandy on its own is bad enough but there’s worse to come. When she gets drunk she will come and find me and press her body on me. The memory of the first time my Mummy does this stays with me for the rest of my life, even though I’m still only four years old.

* * *

She has been drinking as usual and even at this early age I can sense that she’s out of control as she orders me to play with her on the kitchen lino.

Without having any idea what is really going on, or why she’s in the state she’s in, I know that she’s not the same person who walks with me in the woods and it terrifies me. As her face moves towards me I can smell the strong, acrid odour on her breath. Her movements, as she lurches across me, are clumsy and out of control. I just want this Mummy to go away and for my good Mummy to come back, but I know that isn’t going to happen when she takes my hand and places it between her legs.

She is rubbing my hand up and down, up and down, between her legs, against this soft, hairy thing that she calls her minnie. Caught in my fear, I am anxious, desperate even, to please her. I am looking for the slightest signs that I can make Mum happy, to stop the raging anger in her. I continue to rub my hand up and down her minnie until, finally, she pushes it away.

To my relief, she has calmed down and somehow I know I must have been doing the right thing: she has stopped acting strangely now and it’s me who made her feel better. I feel a strange sense of triumph, of achievement. I feel that she needs me and that I can make the bad things go away for her.

I am still frightened but I also feel proud that I have been singled out: my Mummy has asked me to play a game with her and I am the chosen one to do it.

* * *

This morning, Mum and Dad are having an argument. Dad’s often away travelling nowadays and even when he’s at home, he’s not really there. They never spend much time together and when they do, they don’t seem to be happy.

Dad never gets angry or loses his temper and this morning, right in the middle of this very bad row, he is sitting calmly in the front room drinking his coffee. I don’t know whether Mum is drunk or not but she’s very angry and she’s getting more upset by the second. She’s shrieking at Dad and throwing things and I have no idea what he’s done and I even wonder whether he does.

I wish they’d stop but I don’t think they even know I’m there. Suddenly she gets up and throws her cup of coffee all over him. He gets up without a word and walks out of the room and out of the house.

* * *

I am growing more aware of Mum’s drinking. When she drinks I can sense a huge rage in her and I’m starting to see how bad it is for Dad to live with her because I know what it’s like to be in a room with her when she turns into someone else – someone I’m afraid of.

As the days and weeks go on, Dad goes away on his business trips more and more, and I stop asking Mum when he’s coming home.

Finally, one day, I know he won’t be coming back ever again when Mum tells me that she and Dad can’t live together any more and from now on it’s just her and me.

‘Why doesn’t Dad want to live with us, Mummy?’ I ask.

‘He just doesn’t, David,’ she replies dully. I think maybe she’s hoping I won’t ask her again. She’s making jam in the kitchen which is something she enjoys doing, but I sense that this morning she’s doing it to keep busy and to stop herself from falling apart.

‘But why? Tell me why, Mummy.’

‘Because we’re unhappy together, because . . . just don’t keep asking,’ she snaps.

I know better than to ask again when she uses that tone. Instead I go off to the scrapyard and hide in the nooks and crannies of the metal caves, and think about my daddy who talks to me about his bikes and cars and sometimes cracks jokes which I don’t always understand and who won’t be coming home again.

I am starting to cry when I hear footsteps nearby.

‘You there, Dave?’ comes the voice of the scrapyard owner’s son.

‘Be right there, Jeff.’

I climb out of my hidey hole and go and play. My dad won’t be back and there’s no point in asking again.

But it turns out I’m wrong about Dad not coming back. Not only does he return to the house but he also remains in the house. It’s Mum and me who move out – in fact we move exactly three houses away to the other end of the block of four terraced houses. Both houses feel very similar. They have the same sort of furniture, which is another way of saying that they are both pretty bare.

So there’s Dad at one end of the block, and me and Mum at the other end. In the months to come I go from one house to the other, spending huge amounts of time with Mum but very little with Dad. He’s often busy, usually away travelling, and he never seems to talk to me about anything personal to do with me and Mum or our wider family or our lives together. But he still chats easily about cars and bikes and things like that.

Every time I see him I long for a stronger bond between us, but it never happens. I wish he would cuddle me or sit me on his knee, but it hardly ever happens and it makes me feel sad.

* * *

My parents separate around 1973 when I am five but it isn’t until many years later that Dad tells me that even though they both knew their marriage was over, it took some time for them to be able to sit down and talk it through because it could only be done when she wasn’t drinking.

Even by the age of five there is a definite hole in my life developing. I am happy when Mum helps me to fill it by the way she pays me attention. She doesn’t come to me and make me touch her every day – sometimes weeks go by without her coming to me in this way. But when she does, it somehow fulfils a need in us both.

She needs it for reasons that I am too young to understand. The reason for my need is much more simple: I need the attention. Even at this early age, it helps to build a bond between us. As she is now the only active parent I have, I instinctively understand the importance of this.

At the end of those times we spend together, when she wants me to touch her, she never thanks me but she doesn’t tell me off either. That’s to become the norm and that’s how I want it to be.

I have always worked harder to avoid criticism than to chase praise.

I am too young to know that, in reality, my mother is taking advantage of my submissive nature, committing the worst abuse of the power she has over her child that any parent can. I will soon come to realize this, and that’s when the problems really begin.

The free sample has ended.