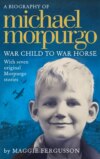

Read the book: «Michael Morpurgo: War Child to War Horse»

michael

morpurgo

War Child to War Horse

A biography by Maggie Fergussonwith stories by Michael Morpurgo

MAGGIE FERGUSSON

Dedication

For

Flora and Izzy

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Preface

1: Beneath the Hornbeam

‘Bubble, Bubble, Toil and Trouble’

2: Spotless Officer Number One

‘A Fine Night, and All’s Well’

3: Situation Critical

‘Littleton 12–Wickhamstead 0’

4: A Winning Formula

‘Didn’t We Have a Lovely Time?’

5: The Heat o’ the Sun

‘A Bit of a Daredevil’

6: Better Answer – Might be Spielberg

‘The Saga of Ragnar Erikson’

7: Still Seeking

‘A Proper Family’

Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Publisher

Preface

Buried in most of us is a desire to communicate with children on their own level. A child falls and scrapes his knee; we drop down to meet him eye to eye. This is the level on which Michael Morpurgo weaves his stories, sharing his thoughts with children in a way that they know is neither contrived nor condescending. Books such as Kensuke’s Kingdom, Private Peaceful, War Horse and Shadow have become contemporary classics, establishing Michael as a kind of Pied Piper for a whole generation. His is a rare gift.

But Michael Morpurgo is very much more than a bestselling children’s author. When his wife, Clare, was getting to know him nearly fifty years ago, she marvelled, in a letter, at his ‘six selfs’. He is many people in one. He remains, in part, a boy of about ten, writing ‘for the child inside myself that I still partly am’. He is a soldier, who won a scholarship to Sandhurst and might now be General Morpurgo had not providence and love combined gently to alter his course. He is a primary-school teacher, whose energy and charisma thrilled his pupils and maddened his colleagues in the staff-room. He is an entrepreneur, whose charity, Farms for City Children, has given more than 100,000 inner-city schoolchildren a taste of what it is like to live and work on a farm. He is a performer, who feels happiest on stage where he is able to forget himself as part of a cast. And he has, recently, become a crusader and statesman, using his fame as a soap-box from which to roar when he encounters injustice.

No wonder Michael’s publishers have repeatedly urged him to write a memoir; but the one story he feels unable to tell is his own, though he is happy for it to be told. When he first proposed that I might write about his life, he was speaking on his mobile from Devon with such a big wind blowing in the background that it was hard to understand what he was saying. Once I had understood, I felt excited but uncertain. How clearly can one hope to see the shape of a life still being lived? And would it not be a mistake to write a book about Michael Morpurgo that had nothing to offer the children who love his work so much? So we struck a deal. I would write seven chapters about Michael’s life; he would read them, reflect on the memories and feelings they stirred in him, and respond to each chapter with a story.

For the past two years, whenever Michael has been in London, I have bicycled from my home in Hammersmith to his riverside flat in Fulham and spent time there getting to know his ‘six selfs’ better. Looking out over the Thames, the tides rising and falling, seagulls crying, we have talked at length about his triumphs, about the struggles he has faced, and about the price he has paid for success. We have explored areas of his life that have remained obscure, perhaps, even to him. What has emerged is a story of light and shade: the light very bright, the shade uncomfortable and sometimes painful. Both light and shade are reflected not only in the chapters I have written, but in Michael’s corresponding stories, some of which have required great courage in the making.

One day Michael Morpurgo must pass, in the words of the old saga-writers, ‘out of the story’. Then the moment will come for somebody to lay another picture on top of this one, and to write a full biography. Here, meantime, is an attempt to catch an extraordinary man on the wing, while he is still in full flight.

MAGGIE FERGUSSON

1 Beneath the Hornbeam

In a corner of Michael Morpurgo’s Devon garden, the ashes of three people share a final resting-place. The sitting room of his low, thatched cottage looks out on the spot where they lie. He passes it every morning on the way to the summer house where he writes. Above it, a hornbeam tree flourishes with such elegance and grace that you might imagine the ashes beneath must be mingled in invigorating harmony. But you’d be wrong. In life, these three people – Michael’s mother, father and stepfather – caused one another untold pain, giving Michael an early education in what he describes as ‘the frailty of happiness’. If you want to understand the thread of grief that runs through almost all his work, you should start here, beneath the hornbeam.

The first ashes to be scattered, on a cold, bright, blossomy day in the spring of 1993, were those of Michael’s mother, Catherine, known from birth by her third name, Kippe (pronounced ‘Kipper’). At her memorial service the congregation had sung the Nunc Dimittis,

Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace …

and they had sung it with full hearts, because for most of Kippe’s life peace had been a stranger to her. She died an alcoholic, pitifully thin, stalked by depression, and convinced, Michael says, ‘that she had failed in the eyes of God’.

How could her life have become so bitter? If Kippe had been a child in a story one might have said that, on her birth in the spring of 1918, the fairies had been generous at her cradle. The fourth of six children, she was beautiful – fair, with a tip-tilted nose and blue-green eyes – and her looks were coveted by her three sisters, who were plainer and more sturdily built. Her father called her his ‘Little White Bird’, echoing J. M. Barrie’s fantasy of infant loveliness and innocence; and, complementing her face, she had a voice that would draw people to her for the rest of her life. Her younger and only surviving sibling, Jeanne, describes it as a ‘brown velvet’ voice, and in a recording made when Kippe was nearing old age it remains melodious, languid and gently seductive – the voice that lured Michael, unbookish boy though he was, into the wonders of words and stories.

Children outside the family were mesmerised by Kippe. Jeanne remembers, more than once, inviting friends home for tea, only to have them admit that what they really desired was to spend time near Kippe. They were fascinated not simply by her looks and voice but by her passionate nature. While other little girls played Mummies and Daddies, what Kippe wanted, from an early age, was to play ‘Lovers’ – and ‘what Kippe wanted, Kippe got’.

Not that her parents went in for spoiling. Their rambling, Edwardian house, ‘The Eyrie’, near Radlett in Hertfordshire, had what seemed to Michael countless rooms, and was set in a large garden with a tennis lawn, an orchard and a dovecote. Yet money was always short. Kippe’s mother, Tita, was a large, imposing woman who gave Michael his first inklings ‘of what God might be like’. Before her marriage she had been a Shakespearean actress. She had a voice so deep and tremendous that she was on one occasion invited to read Grieg’s Bergliot over a full orchestra conducted by Sir Henry Wood, and on another given the part of Abraham in a mystery play at the Albert Hall about the sacrifice of Isaac. Her mother, Marie Brema, had been a professional opera singer, the first from England to appear at Bayreuth. She created the role of the angel in the first performance of Elgar’s Dream of Gerontius, and was once summoned to Buckingham Palace to sing for Queen Victoria. Both mother and daughter were close friends of Bernard Shaw, and when he came to write You Never Can Tell Tita was his model for the feisty and formidable Gloria (‘a mettlesome dominative character,’ in Shaw’s own description, ‘paralysed by the inexperience of her youth’). But neither Tita nor her mother had their heads turned by success. Both were fervent Christian Socialists and most of the money they made on stage was poured into Brema Looms, a workshop providing employment for crippled girls from London’s East End.

In 1906 Tita, who in her late twenties had never so much as kissed a man, had met and fallen in love with a Belgian poet, scholar and nationalist, Emile Cammaerts. There were differences between them. Emile, who had spent much of his youth in an anarchist commune, spoke very little English, and was an atheist. Tita set about tackling both problems with a forcefulness that alarmed Shaw – ‘For Heaven’s sake,’ he warned her, ‘do learn to discriminate between yourself and the Almighty’ – and she succeeded. A Brussels spinster was engaged to teach Emile English (they began their lessons by teasing out Othello, line by line) so that by the time he and Tita were married in 1908 his English was fluent. He had also converted to Christianity with a zeal that would never leave him. As there was little prospect of Tita’s pursuing her stage career in Belgium, and as she felt she must look after her mother, they settled in London, before moving, as their family grew, to Radlett.

Tall, and with a fine, monumental head that would have sat happily amidst the emperors’ busts that ring the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford, Emile Cammaerts became revered in academic and literary circles both for his intellect and for his passionate devotion to Belgium. Invalided out of the First World War with a weak heart, he threw his energies instead into composing fiery, defiant, patriotic poems to encourage his compatriots. Lord Curzon translated his work; Elgar set his ‘Carillon’ (‘Sing, Belgians, Sing’) to music. He was Belgium’s Rupert Brooke. When his fourth child’s birth coincided with a significant Belgian victory over the Germans, he named her after the hamlet, De Kippe, where this had taken place.

Emile Cammaerts, 1943.

But while his Belgian patriotism remained central to him – he went on to become Professor of Belgian Studies at the University of London, and was appointed CBE for organising an exhibition of Flemish art at the Royal Academy in 1927 – Emile Cammaerts also, over time, assumed many of the trappings of the English establishment. He was a member of the Athenaeum, a regular writer of letters to The Times, a close friend of G. K. Chesterton and Walter de la Mare, and such a pillar of the Anglican Church that he considered, in his later years, taking Holy Orders. He was widely loved, and on his death in 1953 the Principal of Pusey House in Oxford described him as ‘a man as near sanctity as I have ever met’.

To Michael, as a small boy, Emile Cammaerts seemed ‘all that a grandfather should be’. He had a flowing beard, thick, tweed suits and heavy brown shoes. He emanated jollity. His theme tunes, in Michael’s memories, are Mozart’s horn concertos, to which he would bounce his grandchildren on his knee; and he had about him what his Times obituary would describe as an air of ‘enchanted innocence’. Though he had made his career as an academic, his earliest published works had been plays for children, and he had written a study of nonsense verse. He would delight Michael with recitals of ‘The Owl and the Pussy-cat’, ‘The Dong with a Luminous Nose’, and, most memorably,

There was an Old Man with a beard,

Who said, ‘It is just as I feared! –

Two Owls and a Hen, four Larks and a Wren,

Have all built their nests in my beard!’

Emile Cammaerts’s reputation was considerably greater than his income, and with six children he and Tita were forced to run the household at the Eyrie along strict make-do-and-mend lines. Jeanne remembers Tita’s darning broken bed springs with 15-amp fuse-wire; and avoiding, wherever possible, spending money on clothes, either for herself or for the children. There was principle at play here, as well as economy. Personal vanity was, in Tita’s book, a vice second only to gossip. She had what Jeanne describes as ‘an almost Islamic desire to hide her figure’, and ‘would happily have dressed herself in sacks’.

There was one area in which indulgence was encouraged. The early lives of both Emile and Tita had been bleak. Tita’s father had separated from her mother soon after her birth, abandoning her to a lonely, rootless existence, trailing with her diva mother round the concert halls and opera houses of Europe. Wildly unfaithful, Emile’s father had, similarly, left his mother, just before his birth, and had, finally, shot himself. Both Emile and Tita, as they grew up, had sought security and comfort in beauty – the beauty of the natural world, and the beauty of art.

At the Eyrie they set out to create a home in which their growing brood would be surrounded and sustained by music and painting and books. ‘Every meal,’ Jeanne laughs, ‘was a seminar.’ Even games of rummy and racing demon bristled with moral and intellectual competition. In the red-linoed first-floor nursery, parents and children gathered round a huge black table to read Shakespeare plays – Tita making a memorable Othello. On Sunday mornings, after church, they congregated by an oak chest filled with postcards of religious paintings by Giotto, Leonardo, Fra Angelico. Each in turn, the children were invited to pick out a postcard and to talk about what it told them of the life of Christ.

With such a rich diet of culture, there was little appetite for material comfort. Asked to choose between a new stair carpet and a gramophone recording of Schubert’s trios, Jeanne and her siblings voted unanimously for Schubert.

Sitting in an armchair in an old people’s home in Oxford, Jeanne, now in her late eighties, looks back with gratitude and love on the home that her parents created: ‘They had no model to go on, but they were trying to make a perfect world for us.’ And to some extent, for a while at least, they succeeded.

But, of the six children, the plain living and high thinking at the Eyrie suited Kippe least well. Her gifts were intuitive rather than intellectual, and at St Albans High School, though she shone on the lacrosse field, the teachers made it clear that she was a disappointment after her academic sisters. She was, perhaps, slightly dyslexic. During the family readings of Shakespeare she stumbled over her parts, and this was bitter to her because she had, in fact, a natural feeling for words and characters. The frustration and humiliation she suffered as a result led her to bully her younger, brighter sister, Jeanne.

Kippe went along with the family ethos of goodness and self-denial, but only intermittently. Sometimes she would tell her siblings that she had set her heart on becoming a nurse, and would post her pocket money penny by penny into the church poor-box. Jeanne remembers her reciting with feeling lines from W. H. Davies:

I hear leaves drinking rain;

I hear rich leaves on top

Giving the poor beneath

Drop after drop …

But increasingly Kippe recognised that what she really wanted was to act. She was so taken up with playing parts, in fact, that her sense of self was fragile.

Unlike her mother, moreover, Kippe minded about her appearance and her clothes. She had a natural taste for glamour and flamboyance, which was denied expression; and the passion that had made her such a thrilling playmate as a child proved, as she began to grow up, more dangerous and double-edged. At nineteen, she fell helplessly in love with a Cambridge friend of her elder brother, Francis. At about the same time she had a bad bout of flu. The two things together proved too much for her, and she suffered a breakdown. It was Jeanne who realised first that something was wrong, coming upon Kippe in their shared bedroom fingering a white-painted chair with the tips of her fingers and murmuring, ‘It’s so cold! The snow is deep.’ For nearly three months, Tita and Emile took it in turns to keep a vigil by Kippe’s bedside as she lay tossing and turning, sometimes calling out so loudly that she could be heard by neighbours beyond the Eyrie garden walls.

Looking back, and with the benefit of long hindsight, Jeanne wonders whether Kippe ever properly recovered; but she recovered sufficiently to leave home and return to the stage. After school she had won a place at RADA, and from there she went on to build a successful career in repertory. It was in the middle of a rehearsal in the Odeon Hall, Canterbury, in the autumn of 1938, that a man called Tony Bridge stepped on to the scene.

There was nothing remarkable-seeming about this new recruit to the company. A year older and slightly shorter than Kippe, he was not especially good-looking. Nor was he, in principle, ‘available’. He too had trained at RADA, where he had met and fallen in love with a fellow student, Betty Mallett. Though not formally engaged, he and Betty were regarded, in his words, as a ‘forever’ couple. Yet within weeks of their meeting, Tony and Kippe – or Kate, as he called her, in affectionate reference to her Shrew-ish tendencies – were spending almost all their time together, heading off into the Kent countryside for long walks when they were not required on stage.

Kippe.

In Tony Bridge, Kippe had found a companion of real kindness, a man with what one of his friends later described as an extraordinary gift for ‘ordinary human understanding’. The only child of lower-middle-class Londoners, he had a talent for amusing people, and for lightening and cheering any company in which he found himself. He made Kippe feel safe and happy. A friend, Mary Niven, remembers a joyful evening she spent with the two of them, during which they sang their way through The Magic Flute, Kippe as Papagena, Tony as Tamino: ‘They triggered each other off. They were lost in delight.’

Not everyone shared their delight. Betty Mallett was, of course, devastated; and Tony’s parents, Edith and Arthur Bridge, were disgusted on Betty’s behalf. They did not warm to Kippe, whom they judged flighty and unreliable. Tony, meanwhile, was not all that Tita and Emile Cammaerts had hoped for Kippe. Quiet and unintellectual, he was, on his first visit to the Eyrie, thoroughly overwhelmed by the Cammaerts tribe; and they were underwhelmed by him. His kindness was mistaken for weakness. Kippe, her parents felt, needed somebody stronger.

Both families hoped that circumstances might drive the couple apart. Through the beautiful summer of 1939, their repertory company played to dwindling audiences until, on the outbreak of war, the Odeon Hall was closed. The following spring Tony Bridge was called up, and for the next eighteen months he was shunted from camp to camp around Britain, settling at last in the Scottish coastal town of Montrose. But separation only strengthened the desire for a more formal union, and on 26 June 1941, during a short army leave, Tony and Kippe were married at Christ Church, Radlett. They are captured in a photograph on the steps of the church, Kippe beaming and beautiful in a Pre-Raphaelite dress, Tony in his army battledress and heavy boots, the Cammaerts and Bridge parents flanking them, smiling as the occasion demanded.

Michael’s parents’ wedding, 26 June 1941. Left to right: Arthur and Edith Bridge, Jeanne and Francis Cammaerts, Tony and Kippe, Elizabeth, Tita and Emile Cammaerts.

The smiles are deceptive. On that early summer day, Emile and Tita Cammaerts, at least, were far from happy – and not simply because they had doubts about their future son-in-law. Less than three months earlier they had received the news that their younger son, Pieter, who had joined the RAF early in the war, had been killed, his body cut from the wreckage of a plane near the RAF base at St Eval in Cornwall. His funeral had been held at Christ Church. As his parents posed for Kippe’s wedding photographs, the earth was still fresh on his grave.

Pieter Cammaerts was just twenty-one when he died, and his death cast a long shadow down the years. A difficult, unsettled child, he had followed Kippe to RADA and had proved himself an actor of real talent, leaving in the spring of 1938 with the Shakespeare Schools Prize. At eighty-six, Jeanne still wipes tears from her eyes as she remembers his winning performance as Claudio in Much Ado About Nothing:

Ay, but to die, and go we know not where …

A fable of heroism grew up around Pieter’s last moments. The story that Kippe clung to – that she passed on to Michael, and that Michael has woven into stories of his own – was that the plane in which Pieter was flying as an observer had been damaged during an enemy attack, and the pilot wounded. Seizing the controls, Pieter had insisted that the rest of the crew parachute to safety leaving him to try to land alone. But a visit to the National Archives in Kew suggests that the truth is more prosaic. Sergeant Pieter Emile Gerald Cammaerts, serving with 101 Squadron, took off from RAF St Eval in a Blenheim bomber on the evening of 30 March 1941 on a mission to Brest – a mission that turned out to be fruitless (‘Target area bombed but no results observed’). On return the plane overshot the end of the runway and crashed, killing Pieter and the pilot, and leaving the third member of the crew severely injured.

Pieter’s siblings reacted in very different ways to his death. His elder brother, Francis, who had, at the outbreak of war, registered as a Conscientious Objector, was now moved to join the Special Operations Executive. He went on to become one of its bravest and most remarkable members, decorated with the DSO, Légion d’honneur and Croix de Guerre. But Kippe was too devastated to do anything but weep. ‘She cast herself as Niobe,’ says Jeanne. ‘She was inconsolable.’ For the rest of her life, if Pieter’s name was mentioned, Kippe would walk out of the room; and on Remembrance Sunday every year she would take herself up to her bedroom and perform a private ritual, placing a poppy beside Pieter’s photograph, and reciting Laurence Binyon’s poem ‘For the Fallen’:

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn …

With every autumn, the words seemed more poignant.

For Michael, growing up, Pieter was a constant presence. When he visited his grandparents at the Eyrie, he was ‘the elephant in the room’, never mentioned, deeply mourned. And wherever Kippe was, Pieter’s handsome half-profile stared down from the photograph that she kept always on her dressing table. Michael so revered Pieter’s self-sacrifice, and felt so desperately for his mother’s sadness, that he would sometimes find himself weeping for the loss of the uncle he had never known. ‘I think they had been really, really close, my mother and Pieter,’ he says now. ‘I think they had been spiritually close.’

Jeanne is impatient with this notion. She remembers Kippe and Pieter getting on particularly badly, and their shared love of acting being a source of friction rather than a bond. Kippe’s grief, and her retrospective reverence for Pieter, she suggests, had their roots in a melodramatic need ‘to be associated with somebody who had done something splendid in the war’.

There is another possibility. Kippe was stubborn. She had stood firm in the face of her parents’ misgivings about her marriage to Tony Bridge. Yet their future together was fraught with uncertainty. Tony had no money and no home. Once the wedding was over, after a brief honeymoon in the Sussex countryside, he was to return to Scotland, and she to her childhood bedroom at the Eyrie. There was no knowing when the war would end, or when they would be able to live normally as a married couple. Kippe was still only twenty-three and it would be surprising if, in the run-up to the wedding, she had not privately felt extremely anxious. Pieter’s death may have given her just the excuse she needed, consciously or not, to vent her anxiety in grief – just as, in the years to come, it would provide an outlet for the sadness that gathered about her from other sources.

Pieter Cammaerts.

Eleven months after the wedding Kippe gave birth to a son and named him, after his uncle, Pieter. He was, from the start, the spitting image of his father – a father of whom he retains not a single childhood memory. Short leaves were few and brief and by the time Kippe realised that she was expecting a second baby, in the early spring of 1943, Tony Bridge was travelling east, via Basra, to the Iranian city of Abadan, where he had been posted with the Paiforce to guard the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company on the banks of the Shatt al-Arab waterway. It was here that he received a telegram from England announcing that a second son, Michael, had been born on 5 October. It was, he noted in his memoirs, ‘joyous news’.

On the morning of Michael’s birth The Times announced that Corsica had fallen to the French Resistance – the first department of France to be liberated. In the days that followed it became clear that the Allies had the Germans on the run. On 7 October the Red Army mounted a new thrust on enemy positions along the river Dnieper, breaking the Germans’ 1,300-mile defence front; a week later Italy declared war on Germany. By the end of the month the Allies were bombing the Reich from Italian soil. In early December the British government announced that there would only be enough turkeys for one in ten families at Christmas, but any sense of joylessness was eased, on Boxing Day, by the news that the British navy had sunk the last of the great German battleships, the Scharnhorst, off the coast of Norway.

For Kippe, relief that the war might soon be over was mixed with apprehension. Since Tony had left for Abadan she had lived in a state of limbo, real life temporarily suspended. Now she was beset by anxieties. What would her husband do when he came home, and how would he provide for her and the boys? Where would they live? Would the Cammaerts family ever learn to respect him? And, more unsettling, did she respect him herself?

At the Eyrie, childhood rivalries and insecurities had continued to fester, and Tony Bridge had become a source of embarrassment to his young wife. His army career was unspectacular. Flat-footed and rather short-sighted, he had not been commissioned as an infantry officer, and had instead been enlisted into the Pioneer Corps – a blow to Kippe’s pride. His letters home were few and dull, much taken up with complaints about the oppressive Persian heat and his troublesome eczema. Just before Pieter’s death, Kippe’s sister Elizabeth had married an officer serving on the North-West Frontier. Jeanne, meanwhile, was engaged to an officer in the 16th Durham Light Infantry. The letters Elizabeth and Jeanne received were frequent, vivid and entertaining, and they delighted in reading them aloud in the nursery at the Eyrie, reawakening in Kippe the feelings of inadequacy and failure that she had suffered as a child.

Yet all might have been well if, as planned, Tony Bridge had returned home in the summer of 1945. Instead, at short notice, his Iranian posting was prolonged, and just when – as Emile Cammaerts later put it – Kippe was ‘keyed up’ to welcome him back, and ‘worn out by the preparations she had made to receive him and by a series of delays and disappointments’, Jeanne’s fiancé, Geoffrey Lindley, visited the Eyrie with an army friend, Jack Morpurgo.

The visit took place on 27 September 1945, and that morning Michael had spoken his first full sentence. Of Kippe’s first impressions of Jack, there is no record; but nearly half a century on Jack’s memories were vivid. ‘The door opened,’ he wrote, ‘and a girl came in carrying a laden tea-tray. It was unmistakably an entrance; all conversation was silenced, Martha had upstaged a whole cast of Marys; but this Martha had all the advantages … All my attention was centred on that tall slim figure, its every movement a delicious conspiracy between art and nature.’ Here was a treasure, he reflected, ‘who would outshine all else in my collection’.

He knew that she was married, but on the train back to St Pancras that evening Jack Morpurgo comforted himself that ‘a girl as precious as Kippe had no need to waste her loveliness on the Pioneer Corps. “As a golden jewel in a pig’s snout …”’ He was determined, from that first meeting, that he would have her.

Jack Morpurgo had all the qualities that Tony Bridge lacked. He was good-looking, witty, glamorous, faintly rakish. ‘Confidence I never lacked,’ he admits in his 1990 autobiography, Master of None, and self-assurance oozes from his description of himself at the time of his meeting with Kippe: ‘a mature senior officer, his face hardened and blackened by years of sun and wind, his hair already touched with grey, the chest of his uniform-jacket blazoned with medal-ribbons, its epaulets sparkling with rank-badges’.

Born to working-class parents in the East End of London, thoroughly indulged by two adoring elder sisters and precociously clever, Jack had, at thirteen, won a scholarship to Christ’s Hospital, a school founded by Edward VI for poor children. From that moment on, he was relentlessly determined to better himself. ‘I wanted my parents to go,’ he wrote, remembering their delivering him at Christ’s Hospital for the first time. ‘They did not belong in all this spaciousness. They could not match the blatant dignity that surrounded us, already even the elegance of my new uniform set me in another world.’

The free excerpt has ended.