This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

Read the book: «Hero»

Praise for Sarah Lean

“Sarah Lean weaves magic and emotion into beautiful stories.”

Cathy Cassidy

“Touching, reflective and lyrical.” Culture supplement,

The Sunday Times

“… beautifully written and moving. A talent to watch.”

The Bookseller

“Sarah Lean’s graceful, miraculous writing will have you weeping one moment and rejoicing the next.”

Katherine Applegate, author of The One and Only Ivan

For my hero, my husband, Nick

Table of Contents

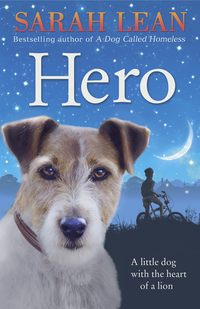

Cover

Title Page

Praise for Sarah Lean

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Sarah Lean

Copyright

About the Publisher

I can fit a whole Roman amphitheatre in my imagination, and still have loads of room. It’s big in there. Much bigger than you think. I can build a dream, a brilliant dream of anything, and be any hero I want …

For most awesome heroic imagined gladiator battles ever, once again the school is proud to present the daydreaming trophy to … Leo Biggs!

That’s also imaginary. You have to pass your trumpet exam to get a certificate (like my big sister Kirsty), or be able to read really fast and remember tons of facts to get an A at school (like my best mate George), before anyone tells you that they’re proud of you. Your family don’t even get you a new bike for your birthday for being a daydreamer, even if you really wanted one.

Daydreaming is the only thing I’m good at and, right here in Clarendon Road, I am a gladiator. The best kind of hero there is.

“Don’t you need your helmet?” George called.

“Oh yeah, I forgot,” I said, cycling back on my old bike to collect it. “Now stand back so you’re in the audience. Stamp your feet a bit and do the thumbs up thing at the end when I win.”

George sat on Mrs Pardoe’s wall, kicking against the bricks, reading his book on space.

“It says in here that meteors don’t normally hit the earth,” George said, “they break up in the atmosphere. So there aren’t going to be any explosions or anything when it comes. Shame.”

“Concentrate, George. You have to pretend you’re in the amphitheatre. They didn’t have books in Roman times … did they?”

“Uh, I don’t think so. They might have had meteors though. People think you can wish on meteors, but it’s not scientific or anything.”

He didn’t close the book and I could tell he was still concentrating on finding out more about the meteor that was on the news. So I put on my gladiator helmet (made out of cardboard, by me) and bowed to my imaginary audience. They rumbled and cheered.

“Jupiter’s coming now. Salute, George, salute!”

The king of all the Roman gods with arms of steel and chest like hills, rolled into the night stars over Clarendon Road like a tsunami. Jupiter was huge and impressive. He sat at the back of the amphitheatre on his own kind of platform and throne, draped his arm over the statue of his lion and nodded. It was me he’d come to watch.

I held up my imaginary sword.

“George!”

George punched the sky without looking up from his book. He couldn’t see or hear what I could: the whole crowd cheering my name from the thick black dark above.

Let the games begin! Jupiter boomed.

The gate opened.

“Here he comes, George!”

“Get him, Leo, get him good.”

The gladiator of Rome came charging up the slope. I twisted and turned on my bike, bumped down off the curb and picked up speed. The crowd were on their feet already and I raised my sword …

And then George’s mum came round the corner.

“George! You’re to come in now for your tea,” she said.

I took off my helmet and put it inside my coat.

“In a minute!” George said. “I’m busy.”

“It’s freezing out here,” she said.

I skidded over on my bike. I whispered, “George! Please stay! It is my birthday. You have to be here, I have to win something today.”

“I’m fine,” he called to his mum. “I’ve got a hat.”

“Yes, but you’re not wearing it.” She came over, pressed her hand to George’s forehead. “You’ve got homework and you’re definitely running a temperature.”

“Gladiators don’t have homework,” I said. George grinned.

“But George does,” his mum said.

“Mum!” His shoulders sagged.

She shook her head. “I think you both ought to be inside. Come on, George, home now.”

“Sorry, gotta go,” he sighed. He slipped off the wall, pulled at the damp from the frosty wall on the back of his trousers. “I’ll come and watch tomorrow.”

“Do your coat up,” George’s mum said as they walked away.

George turned back. “Did you know that Jupiter is just about the closest it ever gets to earth right now?”

I looked up. Jupiter was here, in the night sky over Clarendon Road.

“Yeah, I know, George.”

“I’ll do some research for our Roman presentation.”

“Yeah, good one, see you tomorrow.”

“Leo!”

“What?”

He saluted.

I didn’t want to go home yet though. I really wanted something to go right today.

I bumped the curb on my bike, cruised back into the arena.

The gladiator of Rome was lurking in the shadows between the parked cars. I could smell his sweaty fighting smell, heard his raspy breath. Just in time I hoisted my sword over my head as he attacked. Steel clashed. I held his weight, heaved, turned, advanced, swung. We smashed our swords together again. I felt his strength and mine.

The crowd were up: thousands of creatures and men stamped their feet in the amphitheatre of the sky. Their voices roared. Swords locked, I ducked, twisted, to spin his weapon from his hands. I didn’t see the fallen metal dustbin on the pavement. I braked but my front wheel thumped into the side of it. I catapulted over the bin and landed on the pavement.

The crowd groaned. Jupiter held out his arm, his fist clenched. He punched his thumb to the ground.

I’d never thought that I could lose in my own imagination. Maybe I wasn’t even that good at imagining. I lay there, closed my eyes, sighed. It warmed the inside of my cardboard helmet but nothing else. Everything was going wrong today.

I opened my eyes but it wasn’t the gladiator of Rome looking down at me. It was a little white dog.

I didn’t know if dogs had imaginations or if they thought like us at all, but this little dog looked me right in the eye and turned his head to the side as if he was asking the same question that I was: How can you lose when you’re the hero of your own story? Which was a bit strange seeing as nobody can see what’s in your imagination.

I leaned up on my elbows and stared back. The dog had ginger fur over his ears and eyes, like his own kind of helmet hiding who he really was, and circles like ginger biscuits on his white back.

“Did you see the size of that gladiator?” I said.

The little dog looked kind of interested, so I said, “Do you want to be a gladiator too?”

I think he would have said yes, but just then a great shadow loomed over us.

“Is that you dreaming again, Leo Biggs?” a voice growled.

It was old Grizzly Allen. He had one of those deep voices like it came from underground. If you try and talk as deep as him it hurts your throat.

Grizzly is our neighbour and the most loyal customer at my dad’s café just around the corner on Great Western Road – Ben’s Place. Grizzly was always in there. It was easier and a lot better than cooking for one, he said.

You might tell a dog what you’re imagining, or your best mate, but you don’t tell everyone because it might make you sound stupid.

“I didn’t see the bin. I couldn’t stop.”

Grizzly held out his hand and pulled me up like I was a flea, or something that weighed nothing.

“No bones broken, eh?” he beamed. “Perhaps just something bruised.”

I checked over my bike. The chain had come off and the rusted back brake cable was frayed.

“Aw, man!” I sighed.

“Bit small for you now,” Grizzly said. “Can’t be easy to ride.”

“Yeah, I know. I need a new one.” I shrugged, but I didn’t really want to talk about that. I’d had this bike for four years, got it on my seventh birthday; the handlebars had worn in my grip. They were smooth now, like the tyres and the brake pads and the saddle. I didn’t want to say anything about how I’d thought my parents were getting me a new one for my birthday, today. I guessed they didn’t think I deserved it yet. It wasn’t like I’d passed my Grade 6 trumpet exam, like Kirsty had.

Grizzly picked up my bike as if it was as light as a can opener, leaned it against his wall and lowered himself down, all six feet four of him folded into a crouch.

“Can’t do anything with this here cable.” He sort of growled in his throat, but I didn’t know if that was because he couldn’t fix it or because he was uncomfortable hunkered down like that.

The little dog watched Grizzly’s hairy hands feeding the chain back on the cogs. Grizzly didn’t have a dog and it looked odd, a great big man with that little white and ginger dog standing, all four legs square, by his side.

“Did you get a new dog, Grizzly?”

Actually there was nothing new about that dog, except he was new here in our road. I don’t mean he looked old, because he didn’t. He was almost buzzing with life. There was something ancient about him though. Like one of the gold Roman coins in our museum. Sort of shiny and fresh on the outside, but with years and years of history worn into them.

“He’s not mine,” Grizzly said. “This here is Jack Pepper.” The little dog watched Grizzly’s broad face and his tail swayed at the sound of his own name.

“He belongs to Lucy, my daughter. She’s asked me to look after him for a couple of weeks while she takes herself off for some holiday sunshine over the other side of the world.” He winked at Jack. “We’re keeping each other company for a bit.”

Grizzly steadied himself against the wall so I offered him my shoulder to help him up. He was heavy. His joints creaked and clunked like a worn-out machine and he groaned. Jack Pepper stood between us, looking up as if he wanted to know everything that was going on with Grizzly so he could help. Jack didn’t seem to understand that he wasn’t even as tall as my knee.

My bike was twisted, but Grizzly held the front wheel between his knees and pulled the handlebars with one almighty yank until it was straight again.

“Should do it for now,” he said, “but you’ll have to get down to TrailBlaze to see if they can do something about those brakes.”

He looked at me for a long time before nodding towards the fallen bin, and the rubbish strewn along the pavement. There was a smell of rot and something sharp.

“Jack had his nose to the front door so we came out to look and see if cats were getting in the rubbish.”

“I didn’t see any cats,” I said. “Mrs Pardoe’s big ginger cat went in dad’s shop once and stole a chicken sandwich, right off the side.”

“And who wouldn’t want some of your dad’s delicious food, eh?” Grizzly laughed. “Hear that, Jack? Maybe I’ll be treating you too!”

I picked up the bin, then the empty soup tins and old teabags and threw them back in. Jack Pepper sniffed and sniffed. He didn’t seem to mind whether they were good or bad smells: he just enjoyed sniffing them. I tried to put the lid back on, but it was bent and didn’t fit properly.

Grizzly took the bin and put it back in his front garden, rested the dented lid on top.

“Best keep this out of your way, hey, son?” He smiled, his small eyes shining under his broad lined forehead. He nodded towards my helmet. “Hard to see out of that, eh?”

“Oh, this!” I took my cardboard gladiator helmet off, embarrassed that I’d forgotten I had it on. But Grizzly wasn’t laughing at me. He seemed quite impressed actually. “It’s for a presentation on Romans we have to do at school next week. I’m a gladiator but I don’t like standing up in front of the class.”

“Why’s that then, son?”

In all the imaginary battles that I’d fought in Clarendon Road I could make things turn out just how I wanted (except for today). But things weren’t like that in the real world.

I shrugged. “The kids at school always look bored whenever I talk about something, and our teacher doesn’t notice you unless you’re really clever or really stupid. They think I’m lame, and that gladiators are too. But they’re not.”

“I see.” Grizzly frowned. “George helping you with your presentation?”

“Yeah,” I sighed, “he’s better at research and words than me. I made this instead.” I held out my helmet to show him. “It’s made of cardboard but I painted it.”

Grizzly beamed. “Would you look at that!” he said peering closer. “Thought it was real bronze for a minute.”

“Yeah?”

“Had me fooled!”

I liked that he said that, but then I checked the helmet over and saw that the crest had been crushed when I fell.

“Maybe I should redesign it or make some more armour, you know, like for protection or something.”

“So it matters what other people think, eh?” Grizzly said.

Of course it did.

Grizzly called Jack Pepper to come in, closed the gate and headed for his front door. The little dog stopped and stared at me through the bars of the gate.

“Tell your dad I’ll see him Friday,” Grizzly said. He whistled for Jack Pepper to come but that little dog stood there for the longest time with his tail quivering as if he’d rather come with me and be a gladiator too. Grizzly whistled again and Jack followed this time, still watching me, and I thought I heard Grizzly say, “He won’t win battles by having better armour, will he, Jack?”

Everybody had heard about the meteor that was coming our way. They said we’d even be able to see it flash across the sky from here. I looked out of my bedroom window and imagined Jupiter frowning down at me, disappointed that I’d lost my latest battle.

Jupiter was king of the sky and thunder; he held lightning in his bare hands, ready to hurl it at anybody who annoyed him. I wondered if he threw meteors too. I imagined Jupiter resting his chin on his fist.

Where’s the show then? he grumbled. Where are all the gladiators?

My little sister, Milly, came into my bedroom and stood beside me by the window. She pressed her head against the pane and looked up at the empty sky.

“Is the meteor coming?” she said.

“No, not yet,” I said.

Mrs Pardoe’s ginger cat was in the road though and I watched it to see if it was going to go to Grizzly’s bin.

“What are you looking at then?” Milly said.

I picked her up and sat her on the windowsill. “Look. Watch its shadow.”

The cat trotted through the beams of the street lights.

“It’s a small cat … now it’s growing and growing … now it’s huge!” The shadow shrunk and grew, shrunk and grew again as the animal trotted along the pavement. “It’s pretending to be a lion.”

“Is it?” she gasped.

The cat slunk along, pressed tight against the wall, its tail swinging and twitching.

“It’s stalking, catching prey,” I whispered, making it all dramatic.

Milly’s eyes were wide. “You mean it’s chasing a mouse, but actually it’s pretending it’s going to catch a … a hippopotamus?”

I don’t know why she said hippopotamus. “Well, yeah, but probably an antelope or zebra, that kind of thing.”

“It’s like real but not real,” she said, “and magical.” I smiled. The cat disappeared over a wall. Milly sighed. “Will you come downstairs now? We’re all waiting.”

“Hang on a minute,” I said. I thought I’d show her the helmet and see what she thought, see if she could imagine it too. “Close your eyes a second.”

“I can’t close my eyes,” she said, dead serious.

“Why not?”

“When I do, I keep seeing the meteor and it scares me. What’s going to happen to us?”

“Nothing’s going to happen,” I said. “It’s just going to burn bright for a minute and then it’ll be gone. It’ll be pretty. You’ll like it.”

“Really?” Then she leaned over and whispered, “Tell me the truth. Do you love your new trainers the best?”

I looked down at my feet, turned out my ankles.

“I helped pick them,” she said, staring at my feet too. Milly was only six. I couldn’t tell her that I was disappointed I didn’t get a new bike.

“They are the absolute best trainers ever,” I told her. I put on my Roman helmet, with fierce eyeholes and a terrifying square mouth and curved crest on the top, now held up with sticky tape. “Tell me the truth. Do I look like a gladiator?”

“No, because I know it’s you,” Milly giggled “Now come on, we’ve got a treat.”

“Smart trainers, hey, son?” Dad said from the sofa, taking up two spaces as usual. He spread his hands out towards the coffee table. “We’ve got all your favourites, plus … secret ingredient on the chicken.” He winked and chuckled.

“Garlic,” Mum said, with a knowing nod, and went out to the kitchen.

“Chocolate?” Milly said. “Could it be chocolate?”

“Chilli,” Kirsty said. “I think it’s chilli.”

We did this every time, tried to guess what that extra-special flavour was. We’d probably guessed right a long time ago but Dad would never tell.

“What do you think, Leo, my little dreamer? What’s your best birthday guess?”

I shrugged. “I don’t know.”

“Leo doesn’t know much about anything, apart from playing gladiators!” Kirsty said. “Don’t you think it’s a bit babyish playing pretend games? No wonder you’ve only got one dorky friend.”

Kirsty had loads of friends and everyone liked her but they didn’t know how mean she could be sometimes.

“I think it’s lovely,” Mum said, before Kirsty and me could argue (although gladiators were not lovely!). She was coming back from the kitchen with my birthday cake. It was all lit up and ready to blow out. “Here we are. Dad made it specially.”

Three sponge layers oozed chocolate cream with a load of sweets all spilled over the top. Awesome.

“As it’s your birthday, you can have cake first,” Mum said.

“Can I as well?” Kirsty said. “I am the oldest.”

“And me,” Milly said.

“We’ll all have a big piece of cake first,” Dad grinned.

“Are you going to make a wish?” Milly said.

I blew out the candles, thinking it was a long time until next year to get a new bike.

“Stop it, Leo,” George said, spinning around on his computer chair. “You’re supposed to be helping with our presentation.”

“I’m doing research,” I said.

“Yeah, right.” George swung back to his computer. “Write your ideas down. And get off my bed, you’re messing it up.”

Sometimes I’d forget what I was supposed to be doing and be battling a new gladiator, swept away by the roaring crowd. If I wasn’t doing that in Clarendon Road I’d be at George’s house and he would help us do our homework (he did most of it). George liked books and words. They were his favourite things.

“George?”

“What?”

“How come things from the past are so deep under the earth? I mean, where did all the stuff on top of ancient ruins come from?”

The Romans left a ragged flint wall here, in our town, straight as an arrow along the back of the Rec, which you can still see. They left pots and coins and buckles and pins in the earth, which we stared at when Mr Patterson, our teacher, took us on a field trip to the museum. We stared at the artefacts and I imagined all the people who might have owned them, wondering about what they were like and what their stories were. Were some of them gladiators like me?

“I don’t know,” George said. “It’s erosion or compost or something.”

I opened his book on Romans to find something interesting. I looked at the pictures and caption boxes and read one out.

“Romans invented amphitheatres and arches, and realistic-looking statues, socks—”

“Socks?!”

“That’s what it says, socks and baths, and a law that we still have today, which says you’re innocent until proven guilty.”

“Although if you’re guilty you know you’re guilty, even if nobody proves it,” George said.

“There was also a man called …” I passed the book to George because it was one of those words that looked impossible to say.

“Ptolemy,” he pronounced “Toll-a-me. It’s a silent ‘P’.”

“Oh, right. Anyway, he mapped the stars and joined the dots, and named them after a whole mysterious collection of mythical beasts and animals and gods and heroes. I think I would have liked him, George.”

I had posters of the universe and everything in it stuck up in my bedroom. You could get posters inside Dad’s newspaper every Sunday for free until they covered your ceiling.

I put my gladiator helmet on and saluted to the sky out of the window, to the audience of the stars. I thumped my arm to my chest.

“I will return,” I said and punched my imaginary sword in the air, just to hear the men and gods and monsters cheer.

“Leo!” George said. “The helmet’s good, but do I have to do everything else myself?”

“All right, grumpy,” I said.

I fell back on his bed and crossed out my three lines of notes and tried to write them again. Something weird happens between your imagination and your pencil. I tried hard, really I did, to describe what it was like to be a gladiator. It all felt real and bold and brilliant inside my helmet – and when I was in Clarendon Road with a cosmic crowd to cheer me on – but it was dull and lifeless on paper.

“George, I think I need your help or I might end up letting us down.”

“Give it to me,” he said.

He typed out some of the information from his book. George had enough words for the both of us. He printed out a few pages and handed me two sheets. Lines and lines of words and paragraphs.

“You can read that out in class,” he said. “It’s lots of facts about gladiators.”

“Do you think we should have some pictures in our presentation?” I asked.

He sniffed. “I’m not doing any more. I don’t feel well and I’ve got a headache. Anyway, it’ll be good.”

I wasn’t so sure. This presentation was like a battle all on its own and I needed backup, even for George’s excellent words. I fell on his bed, let the papers float to the ground. I needed to do something so that Dad, Mum, Mr Patterson and the kids at school would know I had a good imagination, that I was good at something, not just relying on George.

“What if I acted out a gladiator battle? Maybe with a tiger or something?”

George did his you-are-kidding face. George is good at knowing when you need to be invisible. “In front of the whole class?” he said. “In front of Warren Miller?”

It was a warning, not a question, and we both knew I wouldn’t do it.

Kirsty said there’s a Warren Miller in every year at school. Ours was the new boy. He walked into our class in September with his chin in the air like he was looking way ahead of us. Some people just have it, whatever ‘it’ is. Everyone tried to impress him, until he gave them a soft punch in the arm and sealed their popularity fate. Or not.

Warren ignored me and George. Everybody usually ignored me and George. Except Beatrix Jones, but then she’s kind of unusual. George and me sat together in class on the far-side desk of the middle row. It’s like a blind spot, which is good for not answering too many questions, but bad if you do want to get noticed. For something. Just once maybe.

“Anyway, we won’t need any of that,” George said. “You’ve got your helmet and I’ve made this.”

From under his desk he pulled out a cut-out-and-build-your-own-amphitheatre, made from white card.

“Nobody else will have anything like this. What do you think?”

George has a different sort of imagination to me. I didn’t say what I was thinking, that perhaps he should have coloured it in before he built it, or drawn people in it.

“Impressive,” I said because he isn’t usually good at arty things, and because he’s my best mate. But I had a horrible feeling that nobody was going to be impressed by either of us.

Not in the real world.

The free sample has ended.