Read the book: «Patrick O’Brian»

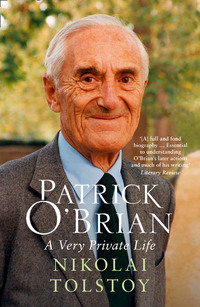

PATRICK O’BRIAN

A Very Private Life

Nikolai Tolstoy

Copyright

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Nikolai Tolstoy 2019

Cover image: Marinepics Ltd/Shutterstock

Nikolai Tolstoy asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All photographs courtesy of the author

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008350581

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008350604

Version: 2020-09-25

Dedication

I dedicate this book to my late cousin Adrian Slack and his sister Julia, the dearest of friends as well as closest of relatives since those distant days of childhood at Appledore beside the Severn Sea.

At home in the cloister of Correch d’en Baus

Epigraph

Indeed I cannot conceive a more perfect mode of writing any man’s life, than not only relating all the most important events of it in their order, but interweaving what he privately wrote, and said, and thought; by which mankind are enabled as it were to see him live, and to ‘live o’er each scene’ with him, as he actually advanced through the several stages of his life.

James Boswell, The Life of Samuel Johnson, LL.D. (London, 1793), i, p. 6

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Preface

I Collioure and Three Bear Witness

II The Catalans

III New Home and New Family

IV Voyages of Adventure

V In the Doldrums

VI A Family Man

VII Master and Commander

VIII The Green Isle Calls

IX Pablo Ruiz Picasso

X Shifting Currents

XI Muddied Waters

XII Travails of Existence

XIII Family Travails

XIV The Sunlit Uplands

XV Epinician Acclaims

XVI Triumph and Tragedy

XVII Melmoth the Wanderer

Envoi

Appendix A: Collioure: History and Landscape

Appendix B: Patrick and His First Wife Elizabeth

Appendix C: Patrick’s Sailing

Footnotes

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Also by Nikolai Tolstoy

About the Publisher

Preface

A fortnight after Patrick O’Brian’s death, the playwright David Mamet wrote of his literary achievement:

Recently I put down O’Brian’s sea novel ‘The Ionian Mission’ and said to my wife, ‘This fellow has created characters and stories that are part of my life.’

She said: ‘Write him a letter. He’s in his 80s. Write him and thank him. And when you are in England, look him up, go tell him.

‘How wonderful,’ she said, ‘to be alive, when he is still alive. Imagine living in the 1890s and being able to converse with Conan Doyle.’

Mamet promptly rehearsed the eulogium with which he would address his literary hero, and began preparing a letter of introduction at his breakfast table. Then, glancing at the newspaper beside him, he saw to his dismay an announcement of the melancholy news of Patrick’s death.[1]

I have no doubt that Patrick would have been delighted by such praise from his acclaimed fellow writer, and that had my mother still been alive she would have inserted the letter in her box-file ‘Valuable Fans and very good reviews’. My hope is that, while nothing can quite replace a face-to-face conversation, this book may compensate by enabling Mamet and others of Patrick’s worldwide legion of admirers to learn much more of his life and personality than might have been obtained from any interview with the famously reclusive writer.

This book covers the latter part of Patrick O’Brian’s life, from the moment of his and my mother’s arrival at Collioure in the south of France in the autumn of 1949. It is the period during which he wrote all his major works. Since my mother’s death twenty years ago, I remain the sole intimate observer of Patrick’s astonishing career from impoverished and little-known writer in 1955, when I first met him, until his death at the height of his international fame at the turn of the millennium forty-five years later. Nevertheless, it never occurred to me at any point during his lifetime to compile his biography – not least because I was well aware of his detestation of inquisitive enquiries into his private life.

My unanticipated decision to undertake the task began in the aftermath of Patrick’s death at the beginning of the year 2000. I was witness to the acute distress caused him by the imminent appearance of an unauthorized biography.[fn1] My dismay was briefly allayed by its publication soon afterwards, when I was asked to review it. My initial impression was that the book appeared largely harmless. Knowing little at the time about Patrick’s early life, and his relationship with his first wife Elizabeth and son Richard, I felt I had no reason not to accept the author’s account of Patrick’s life before I knew him as broadly accurate, and besides dismissed it as of little relevance to his reputation as a writer.

What I was not prepared for, however, was the startling extent to which a small but vociferous coterie of journalists and reviewers eagerly swallowed everything related in the book that could be interpreted as detrimental to Patrick’s reputation, regardless of its truth – or in many instances even likelihood.[fn2] Regrettably, it was in some of the more meretricious cases that his detractors arranged for their pieces to be posted on the internet for futurity.

Before long it occurred to me that I was uniquely placed to provide a more balanced and credible picture. Not only had I known Patrick intimately throughout the greater part of his life,[fn3] but in addition I possess almost all his personal papers, extending from his appearance in a pram at the age of one to his final melancholy sojourn in Dublin. This includes such invaluable sources as my mother’s and his own diaries covering every day of the greater part of the period 1945 to 1999, my mother’s financial accounts from 1945 to 1997, Patrick’s correspondence with his literary agents, publishers and admirers, manuscripts of many of his unpublished works, recorded interviews with his friends and family, extensive personal notes, preliminary drafts of his novels, his precious library, and much else. In addition, I knew intimately many of his and my mother’s friends inhabiting Collioure or visiting them there, almost all of whom are now sadly dead. However, I soon realized that, much more significantly than a desire to refute the damaging effect of media vilification, a biography based on authentic evidence would constitute a remarkable chronicle of love, endeavour, and in some ways unique triumph over daunting odds. In addition it would reveal much of the genesis and inspiration of his admired works of fiction and biography, which continue to enthral millions of readers around the world.

For the rest, it is my hope that this biography will enable readers to arrive at judgements based on evidence, rather than efflorescent imagination. In my experience, truth tends to be vastly more interesting than the most lurid of conjectures. I conclude with an assurance that I have suppressed nothing material from memories extending over five decades and the extensive archive in my possession, save one matter of trifling consequence which for the present I feel it proper to withhold.

Nikolai Tolstoy, 2019

I

Collioure and Three Bear Witness

I went in the loft & there found not only old account books so beautifully kept but our old formally-kept diaries of nearly 30 years ago. How vividly alive we were in those days, or seem to be in this reflection, & how v v little we lived & loved on.

Patrick’s diary, 9 December 1981

In the summer of 1945 Patrick and my mother Mary were compelled to leave London, following the abrupt termination of their wartime employment at Political Warfare Executive. Although they had been very happy during the three years’ tenancy of their elegant Queen Anne house in Chelsea, it was with buoyant excitement that they began their new life in a tiny cottage in a remote valley of North Wales. Patrick welcomed the prospect of entering on a romantic wilderness existence with my mother. His deprivation of many of the normal pleasures of childhood, above all the fellowship of contemporaries, made him by nature unusually self-sufficient. Furthermore, he and my mother were still young (Patrick being then thirty, and my mother twenty-nine), adventurous, and very much in love.

His ambitions were clear. Ever averse to dependence on others, he intended to live so far as possible by the work of his hands, while resuming his precocious career as a writer, which five years of war had compelled him to abandon. Prospects appeared as promising as might be. My mother possessed a modest private income on which they were able to scrape by in their two-roomed house at Cwm Croesor in Snowdonia, whose rent amounted to a mere £4 a year. They were fit, resourceful, and unmaterialistic: a perfect team. Neither ever baulked at hard work, and they rarely repined at the constraints of poverty. Over the bitter winter of 1945–46 they laboured undauntedly to make their home habitable, and toiled at their little garden in order to make themselves as self-sufficient as possible in the coming year. Patrick’s shooting and fishing among the mountains and lakes completed their supply of food.

Nevertheless, the spring of 1946 found him increasingly assailed by frustration and pessimism. Try as he would, his pen failed to flow with its former facility. While my mother’s faith in his talent as a writer never wavered, Patrick increasingly experienced prolonged bouts of writer’s block, a condition which by the end of their four years in Wales had all but overwhelmed him. Moving to a larger house nearby in the valley generated only the briefest spasm of revived creativity, and during the winter of 1948 –49 he began to despair of ever fulfilling his consuming ambition. He grew more and more tense, irritable, self-doubting, and agitated by agonizing thoughts of death and dissolution.[1] In addition the long dark wet winters of North Wales imposed debilitating physical gloom over their lives. Eventually he and my mother decided that their only recourse was to effect a total severance with their current unhappy existence.

After living together for six years, in the summer of 1945 Patrick had married my mother, when he further adopted the decisive course of changing his surname from Russ to O’Brian. Contrary to widespread speculation when this was belatedly made public at the end of his life, I have shown elsewhere that he did not select his new name in order to pass himself off as an Irishman. Indeed, the name itself was chosen effectively at random. His overriding motive was to achieve a total break with his past: above all, to banish all association with his selfish and frequently tyrannical father. However, as failure dogged his every effort to extract himself from the grim predicament he found himself facing, he became increasingly troubled by an obsessive fear that his father’s destructive shadow hung over him, frustrating his every effort to break free. Even the rugged recesses of Snowdonia proved too little protection from the hated oppressor, whose presence he sensed looming above him in forbidding screes or tearing down the valley in raging storms, and eventually it seemed that a second flight afforded the only avenue for escape and renewal.

The bleak Welsh winters no longer proffered an invigorating challenge, but exerted a dampening gloom permeating the little household. By the early summer of 1949, the young couple fastened on the south of France, as refuge from the more and more desperate impasse into which Patrick found himself driven. He returned from an exploratory expedition with the exciting news that he had discovered the ideal spot where they could rebuild their lives.

The little town of Collioure lies on the Mediterranean coast, a few miles from the Spanish frontier. Years later, in his broadly autobiographical novel Richard Temple, Patrick provided a vivid sketch of the impression it first made on him:

The village stood on a rocky bay, with a huge castle jutting out into the middle, and a path led round underneath this castle to a farther beach and farther rocks … A jetty ran out at the end of the second beach … and as he walked along the jetty … he took in a host of vivid impressions – the brilliance of the open sea, white horses, the violet shadows of the clouds. From the end of the jetty the whole village could be seen, arranged in two curves; the sun had softened the colour of the tiled roofs to a more or less uniform pale strawberry, but all the flat-fronted houses were washed or painted different colours, and they might all have been chosen by an angel of the Lord … the high-prowed open fishing-boats were also painted with astonishing and successful colours: they lay in two rows that repeated the curves of the bay, and their long, arched, archaic lateen yards crossed their short leaning masts like a complexity of wings.[2]

The couple arrived at the town in the beginning of September, which is generally one of the best months of the year on the Côte Vermeille. Tourists had departed, and the little town reverted to its workaday existence. The brilliant sunshine was tempered by a pleasant freshness in the air, with the Pyrenees looming behind the town standing out sharp and clear against a pure azure sky.

During his prefatory visit Patrick had already made a few friends. Among these was a beautiful Colliourencque[fn1] (as the town’s female inhabitants are termed), Odette Boutet. Odette was married to a sculptor and painter named François Bernardi.[fn2] They met again the day after Patrick’s return with my mother, when the two couples immediately became fast friends. During his initial visit Odette had helped Patrick find a small apartement on the second floor of 39, rue Arago,[fn3] situated opposite a great gateway opening through the town wall onto the seafront. There was a living room, bedroom, a windowless nook known as ‘the black hole’, a bathroom with shower, and a tiny lavatory.

Always hospitable to a fault, when guests came to stay my parents customarily abandoned the bedroom, ensconcing themselves on lilos, inflatable mattresses, in the black hole. Electricity only arrived in the apartement nine months after their arrival. Inadequate heating was initially provided by a small bottled-gas cooker, and it was not until towards the end of 1953 that they managed to afford ‘a beautiful blue enamelled stove, a flexible desk-light for P. & various other things … Very pleased with stove. It was too heavy for P & me but P & Rimbaud managed.’ This was the Mirus, a handsome and extremely effective heater, capable of burning coal or wood. Cooking was conducted on a small ‘Wonder Oven’, operating on bottled gas.

Apart from the inevitable proliferation of tourist shops and restaurants and the regrettable removal of cobblestones from the streets, the appearance of Collioure within its town walls is not greatly changed since my parents first lived there. Most streets are so narrow that the inhabitants might almost touch hands from opposite windows. Behind the rue Arago, clustered houses along winding passages ascend the hillside to the base of Fort Miradou, while a couple of streets away the Place de la Mairie provided a pleasant refuge under the shade of its plane trees, where townspeople strolled and gossiped in the evenings.

In one major respect, however, Collioure has changed beyond recognition. Some time ago, when I was discussing the town with an old family friend, widow of a retired Colliourench fisherman, she described the new Musée de Collioure in the Faubourg. It contains many pleasing relics of former local life: fishing gear, old photographs, household implements, and so forth. ‘But one aspect it can never show,’ Hélène Camps observed emphatically, ‘is the incessant and extraordinary noise we all knew in those days’ – whether inside or outside the town. For many years all coastal road traffic to Spain passed through the heart of Collioure. Eventually this came to be diverted inland through a massive road tunnel constructed beyond the railway line.

In 1954 Patrick wrote this lively description for the American magazine Homes and Gardens:[fn4]

Where the foothills of the Pyrenees plunge directly to the sea, the smooth-rounded Mediterranean sea that has bitten away the land in black cliffs there, the road winds and winds interminably: hair-pin bends writhe down to the gaunt bridges that stand over naked, dried up river-beds, and from each ravine the road twists upwards through cuttings in the red-black rock to the narrow back of the hill – up, and down again. It is a nightmare for a nervous driver in a hurry, for the lorries from Port Vendres, the buses and the cars tear furiously round the corners – blind corners – screaming brutally with their tyres, klaxons, horns. They all disregard the most elementary precautions (no Latin soul should ever drive a car) and a stranger might well demand whoever had established the theory that the French drive on the right side of the road.

But in the autumn, when the tide of summer cars has slackened, and before the schooners from the south have begun to bring up the oranges that load the lorries in the port, then one can walk safely on the road, follow its turning through the hills and look with tranquillity on the sea below or up to the mountains on the right hand.

This is the time of the vendanges. The hills, terraced with inconceivable labour to the height of the fertile land, are covered everywhere with vines, and the vines are ready.

Although families native to Collioure still live in and around the town, many houses and flats now sadly belong to absentee owners, a proportion of whom I understand do not even appear for some eleven months of the year. In contrast, Collioure in the Forties and Fifties was overwhelmingly home to Colliourench fishermen and their families. Most were closely interrelated through marriage, with links in many cases extending back for centuries. An unfortunate consequence of this was a never-ending spate of raucous conversations conducted throughout the day and much of the night, not only within the houses, whose windows for much of the year were opened wide to the mild air, but also between relatives or neighbours living on opposite sides of the narrow streets. My mother, who might have felt herself back in the Devonshire fishing village of her childhood, was able to tolerate this with fair equanimity. For the edgy and introspective Patrick, however, the hurly-burly proved a constant trial of his temper. His ears were jarred by hoarsely jocose cries of fishermen, high-pitched exchanges between wives and daughters, and maddening screams from their children. ‘Everyone evidently assumed everyone else was deaf,’ he once remarked to me.

Rare objections to the cacophony achieved little more than to exacerbate it:

Last night the Puits [the restaurant on the ground floor] made such a din: Mme R[imbaud]. told me Franco it was who threw the bottle last year: Pilar told her today. P[ilar] & F[ranco] keep cailloux [pebbles] on their window-sill.

This entry in my mother’s diary alludes to an outraged assault on late-night revellers in the restaurant on the ground floor. A year later, to her evident satisfaction, there was a repeat attack: ‘Last night someone threw a bottle outside the Puits: it made a fine noise.’ These incidents provoked inconclusive police and private investigations, all conducted at stentorian level on the spot, the fallout from which their friend Odette once told me had not entirely subsided half a century later.

As though this were not trial enough, Patrick understood barely a word of these vociferous exchanges, since almost everyone’s first or even sole language was Catalan. The occasional bilingual exchange was as often as not equally hard to understand. As my mother recorded:

The woman opposite went bankrupt, & left to live at Elne. There she took up with a man & they came back to live at her house here. His wife found out where they were, & on Sunday came & tried to get at them. They barred their door & she sat on a chair in the Street for six hours. A filthy scene (woman screeching French – man Catalan) by the arch 3 days ago must have been them, I think. The woman was dragging a 4–6 year old child with her.[fn5]

If the human cacophony momentarily waned in the early hours, it was only to be replaced by horrid war cries uttered by the martial cats of Collioure, who waged internecine conflict around gutters, doorways, and up and down stairs – there being generally no doors at street level to communal entrances. Even my parents’ tough little Welsh hunt terrier Buddug could barely hold her own against these feline hosts of Midian. She was enabled to sally forth at will through an entrance cut in the door to the flat. One fine spring day my mother reported: ‘Cats (toms) infest stairs, & Budd rages. She came in with v. bloody nose this morning.’ Their morals were as depraved as their conduct was aggressive. On 9 September 1951 my mother adopted a kitten from the rue, whom she named Pussit Tassit, entering her arrival at the appropriate date in her childhood Christopher Robin Birthday Book. The following May, Patrick ‘saw our cat being covered in the street by a large black tom while half a dozen others sat quietly watching’.

My mother’s diary entries regularly attest to the strain imposed by the unrelenting cacophony:

‘Our rue gets more & more noisy’; ‘Oh God I am so sick with hearing vicious slaps & more vicious screaming at Martine. Patrick tried to read a T.S.E[liot]. poem [Burnt Norton] aloud yesterday but was drowned by the noise in the rue. Both boiled this morning as cats howling kept us from sleeping’; ‘V. bad night: noises’; ‘Street noises formidable’; ‘Neither of us can sleep: too much noise.’

When their neighbour Madame Rimbaud fell ill and was visited by the doctor, his ministrations were accompanied by well-intentioned ‘Shoutings of choruses of women down there all day’.

Despite the disadvantages of their cramped quarters and noisy surroundings, my parents remained at first broadly satisfied with their new home, and swiftly became profound lovers of Collioure and its inhabitants. Their isolated and unproductive life in Snowdonia had long strained Patrick’s nerves to desperation, and there could be no doubting the truth of his parting aphorism: ‘it is better to be poor in a warm country.’[fn6]

In fact the weather at Collioure was far from being balmy throughout the entirety of the year. Winters could prove bitterly cold, and one snowstorm was so heavy that roofs collapsed beneath the weight. In January 1954 my mother recorded: ‘Snow thick from Al Ras to Massane; cold & it rained all night’, and shortly afterwards: ‘Rain in the night, & today the Dugommier hillside specked with snow. They say 15° [Fahrenheit] below zero at Font Romeu.’ I remember seeing in the town at that time photographs of what I recall as enormous waves frozen in mid-air as the sea hurled itself against the town walls. Life in the tiny flat above the rue Arago could be harsh indeed: ‘Ice on comportes in the rue; glacial wind. Mirus [stove] full blast hardly keeps us warm’; ‘Still 23° without, washing frozen into boards … Frightful cold: P. works au coin du feu.’

In spring the ‘maddening, howling tramontane’ battered the region for frustrating weeks, while in the autumn ‘Wind (from Spain) & clouds prevented plage. C’est le vent d’Espagne – il fait humide – c’est pas sain.’

Port d’Avall and Château St Elme under snow in 1954[fn7]

Of course much of the year was generally hot, but even then freak weather could strike Collioure’s microclimate, arising from its situation between the mountains and the sea. July 1953 saw a ‘fantastic hail storm … River vast red flow.’ Much of this belongs to the past, owing to climate change, but is important to recall when reliving my parents’ early days in Collioure.

A hostile critic has conjectured that Patrick’s move to Collioure was undertaken ‘perhaps, in order to be a long way from the family he had abandoned’.[3] In reality, seven years had passed since he finally left his first wife Elizabeth for my mother. Moreover, he continued in close touch with his young son Richard, the only other member of his immediate family, whom he had no intention of abandoning, while he maintained intermittent correspondence with his brothers, sisters and stepmother throughout the long years that lay ahead.

It is true that relations with his son had been troubled, although nothing approaching the extent alleged by subsequent critics. Richard O’Brian was, by his own admission, somewhat indolent as a child, and made unsatisfactory progress at the Devonshire preparatory school to which his father and my mother had sent him for two and a half years at great financial sacrifice to themselves. At the end of the summer term of 1947 Patrick was obliged to withdraw him, and set about teaching him at the house where he and my mother were living in North Wales. Although the boy’s education improved considerably in consequence, in some respects the experience was an unhappy one. Patrick’s own wretched childhood had left him constitutionally ill-equipped (for much of his adult life, at any rate) to deal with small children, a failing on occasion so pronounced as to be all but comical. Walking above Collioure in November 1951, he fled down a sidetrack on ‘seeing some beastly little boys’ – one of several similarly alarming encounters. He imposed what might now appear excessively rigorous discipline on his son during lessons. Although Richard regularly stayed with his mother in London during the ‘school holidays’, during his time in Wales he had missed her and his beloved boxer Sian acutely. Patrick and my mother were fond of dogs, but it was impossible to introduce Sian into the sheep-farming community of Cwm Croesor.

This regime continued for two years, during which time excruciating attacks of writer’s block made Patrick more and more testy and uncompromising in his efforts to educate the boy. It is likely that Patrick’s frustration with Richard’s lack of satisfactory progress was exacerbated by his own inability to achieve anything constructive in his writing. On the other hand, outside lessons he became in marked contrast a strikingly adventurous and imaginative parent. My mother’s unwavering affection, too, went far to ameliorate Richard’s life. Eventually, the ill-conceived scheme came to an end, with the departure of Patrick and my mother for Collioure in September 1949. That July Richard’s mother Elizabeth married her longstanding lover John Le Mee-Power, which enabled her to make a successful application to the courts to recover custody of her son.

Patrick was deeply concerned to secure the best education possible for Richard. In 1945 he had registered him for entry to Wellington College, a public school with a strong military tradition, with a view to his eventually obtaining a career in the Army. Unfortunately this was my father’s old school, which I in turn entered in January 1949. When my father was informed by Elizabeth that the O’Brians planned to send Richard there, he managed to persuade the Master of the undesirability of his attending the same school as me. The fact that my mother was at the time denied all contact with me presumably influenced the College’s concurrence with my father’s objection, which would now seem harsh and arbitrary. It is possible that some future unhappiness might have been avoided, had Richard and I been permitted to become friends from an early age.

The sincerity of Patrick’s concern to advance Richard’s education and future career cannot be doubted. The annual fees for Wellington were £160–£175 a year, which together with travel and additional expenses required a total expenditure of about £200 per annum. Yet his and my mother’s combined income for 1950–51 amounted to £341 6s 9d.[fn8] Nor was the proposed sacrifice any fanciful project, since they had earlier paid about £170 a year for Richard’s preparatory school fees and expenses.[4]

Eventually Richard came to believe that his father had contributed nothing material towards his education. In a press interview conducted over half a century later, he declared: ‘My father never offered to help … [I] had been sent to a boarding school in Devon by [my] mother … [My] mother found the fees increasingly difficult to pay.’[5]