This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

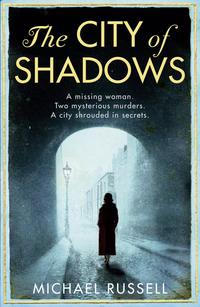

Read the book: «The City of Shadows»

MICHAEL RUSSELL

The City of Shadows

For Anita

I have been here before,

But when or how I cannot tell;

I know the grass beyond the door,

The sweet keen smell.

‘Sudden Light’

Dante Gabriel Rossetti

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One: Free State

1. The Phoenix Park

2. Merrion Square

3. Harold’s Cross

4. Stephen’s Green

5. Clanbrassil Street

6. Kilranelagh Hill

7. The Mater Hospital

8. Kilmashogue

9. The Gate

10. Red Cow Lane

11. Adelaide Road

12. Weaver’s Square

Part Two: Free City

13. Oliva Cathedral

14. Danzig-Langfuhr

15. Zoppot Pier

16. Mattenbuden Bridge

17. The Forest Opera

18. Silberhütte

19. The Westerplatte

20. The Dead Vistula

Part Three: Free Will

21. Glenmalure

22. Dorset Street

23. Westland Row

24. Baltinglass Hill

A Tale of Two Treaties

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PART ONE

Free State

Inthe back drawing-room there was a quantity of medical and electrical apparatus. From the ceiling, operated by pulleys, was a large 170 centimetre shadow less operating lamp hanging over a canvas covered object – when the cover was removed it was found to be a gynaecological chair with foot rests. The detective sergeant found a specially padded belt that could be used in conjunction with the chair. Among the objects found in the drawing-room was a sterilising case, in the drawer of which were wads of cotton wool. In the office there was a cardboard box containing a dozen contraceptives and a revolver.

The Irish Times

1. The Phoenix Park

Dublin, June 1932

The moon shone on the Liffey as it moved quietly through Dublin, towards the sea. The river was sparkling. Silver and gold flecks of light shimmered and played between the canal-like embankments of stone and concrete that squeezed it tightly into the city’s streets. By day the river was grey and sluggish, even in sunlight, darker than its sheer walls, dingier and duller than the noisy confusion of buildings that lined the Quays on either side. Its wilder origins, in the emptiness of the Wicklow Mountains, seemed long forgotten as it slid, strait-jacketed and servile, through the city it had given birth to. It wasn’t the kind of river anyone stood and looked at for long. It had neither majesty nor magic. Its spirit had been tamed, even if its city never had been. From Arran Quay to Bachelor’s Walk on one side, from Usher’s Quay to Aston Quay on the other, you walked above the river that oozed below like a great, grey drain. And if you did look at it, crossing from the Southside to the Northside, over Gratton Bridge, the Halfpenny Bridge, O’Connell Bridge, it wasn’t the Liffey itself that held your gaze, but the soft light on the horizon where it escaped its walls and found its way into the sea at last. Yet, sometimes, when the moon was low and heavy over the city, the Liffey seemed to remember the light of the moon and the stars in the mountains, and the nights when its cascading streams were the only sound.

It was three o’clock in the morning as Vincent Walsh walked west along Ormond Quay. There was still no hint of dawn in the night sky. He had no reason at all to imagine that this would be the last day of his short life of only twenty-three years. He caught the glittering moonlight on the water. He saw the Liffey every day and never noticed it, but tonight it was full of light and full of life. More than a good omen, it felt like a blessing, cutting through the darkness that weighed him down. It was a fine night and surely a fine day to come. Turning a corner he saw lights everywhere now, lighting up the fronts of buildings, strung between the lampposts along the Quays, illuminating every shop and every bar. Curtains were drawn back to show lamps and candles in the windows of every home. The night was filling up with people. The streets had been empty, even fifteen minutes ago, when he’d set off from Red Cow Lane, but suddenly there were figures in the darkness, more and more of them now, in front, behind, crossing over the bridges from south of the river, all walking in the same direction: west.

A stream of Dubliners moved along with him, flowing in the opposite direction to the Liffey, growing at every tributary junction that fed into the Quays. Men and women on their own, quiet and purposeful; couples, old and young, silent and garrulous, some holding hands like lovers and some oblivious of one another; families pushing prams and pulling stubborn toddlers, while youngsters of every age raced in and out of the throng with growing excitement. There were young men who walked in quiet, sober groups, some fingering a rosary, and others full of raucous good humour; women and girls, arm in arm in lines across the street, gossiping and giggling as eager, teasing, endless words tumbled out of their mouths. Occasionally the whole population of a side street decorated with flowers and banners erupted out to join the flow of people moving towards the Phoenix Park. Vincent Walsh glanced back to see the first pink glow behind him in the sky. The new day was coming. And it was as if everyone around him had that same thought at once, as if all those footsteps, already full of such happy anticipation, were moving even faster now, more purposefully and more exuberantly forward, to the gates that led into the Park.

The noise was suddenly much louder. Everyone was talking. The sense of being a part of it all, of belonging to it all, of being absorbed into this hopeful stream of humanity, was irresistible. It wasn’t something Vincent wanted to resist. He was fighting back tears, even as his face beamed and smiled in response to the joyful faces around him. This was how he wanted to feel; it was how, when this day ended, he knew he could never be allowed to feel. As they all poured through the Park gates together it was quiet again for a moment. Abruptly the night had opened up around them. Dublin, always so closed and crowding in on itself, was gone. There was only the rhythmic sound of thousands of feet on grass and gravel, and the sight of thousands of shadows amongst the trees of the Phoenix Park.

As full daylight came, the tramp of feet and the clamour of voices grew louder. Vincent had tried to sleep but he didn’t really want to. His heart, like everyone else’s, was beating to the sound of those feet and, like everyone else, he couldn’t tire of simply watching the arriving masses. From a stream to a torrent now, melding to form great banks and squares of humanity as far as the eye could see. By eight o’clock the cars and the coaches were coming too, from every corner of Ireland. Someone said there must be a million already, a million people there to bear witness to the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Someone said the Eucharistic Congress was the final victory for Ireland, after hundreds of years of faith in the face of persecution, flight and famine. Someone said, and at some length, that for anyone who thought there was no such thing as democracy, here was enough real democracy to right the whole shipwreck of the world. Someone said even the angels looking down from the gold bar of heaven could see them there. Someone said it was the greatest loudspeaker system the earth had ever known, stretching fifteen miles through the Park and into the city. Someone else said the angels should have no trouble hearing so. And in front of the crowd, close to where Vincent was sitting, was the high altar that would be the focus of a million devoted faces that day. It shone in the morning sunlight, radiantly white against the dark phalanxes of the faithful, with its two great arms of pillared colonnades, echoing the colonnades of St Peter’s in Rome, reaching out to hold a million people in a joyful embrace.

There was really no plan. He knew the block of seats where the priest would be giving communion. They’d talked about it, weeks before, the last time they’d been together. They had talked about everything that night, everything that mattered to them, everything they felt passionate about, everything they’d ever dreamed about. Vincent had never felt closer to anyone. He had never felt such belonging. He had never felt such an all-possessing love. The priest didn’t meet him the next day, or the next, or the next. He’d promised he’d be there, waiting in his car in Smithfield, but he didn’t come. And there’d been no more letters. But it was understandable. The Eucharistic Congress meant so much work for any priest, every priest. Today he would see him. He would be at the Pontifical Mass. The priest had been so proud, so excited about serving so close to the high altar. And Vincent would find him. It would happen. Irrespective of tickets and passes and seat allocations and stewards, it would happen. There would be a million people in the Phoenix Park, a million people full of hope. And no hope was stronger than Vincent’s. If he had had doubts as he set out in the darkness that morning, he had breathed in the intoxicating faith that was all around him now, and he had been consumed by it.

Vincent had been watching a group of stewards and workmen as they struggled to unload a trailer of heavy benches in front of the high altar. People were already being moved back from the areas reserved for the great and the good. They would have no need to arrive before dawn and stand there all morning. He spoke to the big man who was so cheerfully in charge.

‘Is there anything I can do to help?’

‘There’s still benches to be shifted. We can’t have the bigwigs standing up, not when they’ve brought their arses with them to sit on.’

He worked through the morning, carrying benches and chairs and lining them up in rows. He brought plants and flowers to the colonnades of the high altar. He fetched kettles of tea for the stewards and the labourers, and he picked up their litter. The more he worked, the more he let himself sink into a sense of belonging that was utterly unfamiliar to him. The Eucharistic Congress had seemed a long way from him a week ago, even though it was the only thing anybody was talking about. It filled Dublin and Ireland and the hearts and minds of everyone in it. But it had had nothing to do with him until now, except as the chink of light that offered him a way to find the man he loved. Now it felt different. He didn’t forget why he was there, not for a moment, but he hadn’t expected to be absorbed into the day like this. Suddenly it was his day too. He had contributed his sweat to it. And when the work was done and a hush of anticipation descended on the Phoenix Park, the steward he’d first spoken to slapped him on the back.

‘You may stay at the front, lad. You’ve done more than your share.’

The cavalry came first, lances held high, escorting the carriages and the cars that brought the world’s cardinals, archbishops and bishops to the high altar. They were followed by politicians and ambassadors in tails and top hats, businessmen and union leaders, and the banners of almost every society, association and club in Ireland that could come up with a halfway decent reason to be there. They were led by the graciously waving hand of Éamon de Valera. Ten years ago he had gone to war with the independent Irish state he helped wrest from British rule, because it wasn’t independent enough. Then, if some of the Irishmen he had fought beside against the British had caught him, he would have been shot. He had been excommunicated by the Church during the Civil War that followed the War of Independence, when old comrades killed one another because of the six counties that remained under British rule, and an oath to the English king that no one took any notice of, even in London. But now Dev had returned triumphantly from the political wilderness. Now he was the president of the Free State he despised.

Meanwhile a purple and crimson thread of prelates made its way through the thousands of robed priests in front of the altar. For seconds it was so quiet that the birds could be heard singing in the trees; there was the cry of a solitary gull sailing overhead. Cardinal Lauri, the Papal Legate, read the Pope’s words to the crowd. ‘Go to Ireland in my name and say to the good people assembled there that the Holy Father loves Ireland and sends to its inhabitants and visitors not the usual apostolic blessing but a very special all-embracing one.’ And as the Mass started Vincent simply walked to where he wanted to be, where he had to be. ‘Introibo ad altare deo.’ I shall go unto the altar of the Lord. He answered the Cardinal’s words with words he had not spoken in many years. ‘Ad Deum qui laetificat iuventutem meam.’ To God who giveth joy to my youth. Once he had spoken those words as an altar boy. But slowly, painfully, not even understanding why at first, he had seen all the words he knew by heart come to feel like someone else’s. They couldn’t belong to him any more, and worse he couldn’t belong to them. But today they were his again. He held them close, like childhood friends. He hadn’t understood how much he wanted them to be his again.

There were moments in the Mass when he felt the happiness of a childhood that had been ripped away from him by his consciousness of who he was. Was it really impossible to find a way back when he could feel like this? Suddenly he realised that the time had come. The Cardinal had elevated the host that brought Christ’s presence into the life of every one of the million men, women and children now on their knees. Three thousand priests moved out into the crowd with the Eucharist. And for the first time that day, there was doubt in Vincent’s mind. He had still not seen him. He had looked and looked, hoping, believing. Only now did he feel fear, a growing fear that despite everything the priest was not there, that something had happened, that he was lost in a crowd that was a quarter of the population of Ireland.

But then he saw him, shockingly close, moving forward with the chalice, along the line of kneeling figures towards him, just as the passionate voice of John McCormack soared up from the high altar, where he stood in the red and gold and black velvet tunic of a Papal Count. ‘Panis Angelicus.’ Bread of Angels. The bread of angels becomes the bread of man. O miracle of miracles. The priest was too absorbed in what he was doing, too full of the sanctity of the moment, even to see anyone he served the host to; each kneeling form, hands clasped in prayer, each tongue protruding to take the bread of the angels. And it was almost as the priest reached him that Vincent took the note from his pocket. ‘I will wait for you after. I will wait for you. Vincent.’ He had written more at first, much more, over and over again, but each time he had thrown the note away. There would be time to say all that. And there would be ways to say it without any words. He was shaking now as the priest stood in front of him. ‘O res mirabilis!’ As the host left his lover’s hand and rested on his tongue, Vincent pushed the tightly folded note at him. The man stared down. It was a look first of nothing more than broken concentration and surprise, but it was followed by confusion, and then fear.

The kneeling figure looked up at the priest with an expression of almost beatific devotion. The moment lasted only seconds, though for both men it seemed much longer. For Vincent it was as if the million people in the Park were no longer there. For the priest it felt as if a million pairs of eyes were looking into his soul, horrified by what was there. He moved on abruptly to offer the host to the next communicant. Vincent closed his eyes in a prayer of thanks. He had seen neither the confusion nor the fear on his lover’s face. He hadn’t seen the tightly folded note, screwed instantly into an even tighter ball, fall to the ground to be trodden underfoot, unread. And as the Mass ended and a million people went in peace, Vincent Walsh simply sat and watched them go – the people, the cars, the carriages, the politicians, the priests and the prelates. He watched until the stewards and soldiers and policemen were leaving too. He watched until long after he knew that his faith in that day was not going to be fulfilled, until long after all the hope that he had shared with a million people that day had drained away.

There was darkness in the sky now. The policeman had been eyeing him on and off for over an hour. He walked towards Vincent with a look of distaste.

‘It’s time you were away from here.’

‘I was waiting for someone.’

‘I don’t see anyone left to wait for. You heard what I said. Off.’

‘He still might –’

Vincent stopped. The world he had forgotten about since the early hours of that morning, looking down at the shimmering, moonlit waters of the Liffey, the world he really lived in, the world in which he was a permanent and unwanted stranger, was there in front of him again. Even those words, ‘He still might –’, said in the way he’d said them, were enough. This guard he had never seen before already knew him. The expression of contempt and disgust was palpable, already like a punch, like the real punches that had so often come with that look in the past. It wouldn’t be the first time they had come from the police officers of the Garda Síochána.

‘If you want the shite kicked out of you, there’s a few of us would be happy enough. Are you up for that?’

Almost anything Vincent said would provoke a beating. He knew the look too well. There was a group of gardaí, smoking close by. They were watching him too. It was the same look. He got up and turned away, without another word. He walked back through the Park, back to the river, back along the Quays. Everywhere there were people. They still filled the streets, more and more of them as he got closer to the city centre, where the parades and processions had continued all afternoon. The whole place was full of people celebrating this day that had been like no other. But for Vincent Walsh it was a day like every day again; like every day had been for years.

*

He walked into Carolan’s Bar. He nodded in response to the greetings, but there was nothing behind the smile he forced out of himself. He stepped in behind the bar. For a moment Billy Donnelly said nothing. Then he picked up a bottle of Bushmills and half-filled a tumbler. He thrust it into Vincent’s hand. Billy didn’t need an explanation. Hadn’t he known the outcome?

‘What else did you expect? I told you.’

‘You’re a fecking clairvoyant, Billy.’

Vincent put the glass to his lips. He didn’t want it but he drank it.

‘Jesus wept, Vinnie. If I’d a pound for every man here was fucked by a priest and never saw him again, I’d be the richest man in Ireland!’

‘You don’t know anything about him.’

‘I’ve met his sort in every jacks in Dublin. We all have.’

‘You’re a gobshite.’

‘I am and I wouldn’t know an angel if he was up my arse. It’s why I’ll never get to heaven. Go on, forget about working tonight. Get off and see some of your pals. Or take the bottle upstairs and shout at the moon.’

‘I’ll be better doing something, even listening to a bollocks all night.’

Billy grinned. He reached for the Bushmills again and refilled the tumbler. Vincent drank it down in one. He’d the taste for it now. He turned back to the bar and grabbed one of the empty glasses thrusting towards him.

‘Another pint if that’s the sweet nothing’s all over with now!’

‘In the glass or will I pump it straight into your great, gaping gob?’

‘If that’s what’s on offer I’ll have the pint afterwards so.’

Vincent laughed with everyone else. The cramped bar at Carolan’s smelt of stale beer and sweat and cheap aftershave. Once in a blue moon Billy Donnelly decided the place had to be cleaned properly, and for the next week it smelt so strongly of Jeyes Fluid that when the smell of the stale beer, sweat and aftershave returned, it was like the breath of spring. Vincent looked around at the noisy crowd of regulars; the screeching queens with rouged cheeks; the swaggering boys always giggling too much; the big men with moustaches and muscles and paunches; the tweed-jacketed pipe smokers who jumped every time the door opened and kept their wedding rings in their pockets. It wasn’t a place you could really say you belonged, but it was safe. It shut out a world where belonging was out of the question. The Guards knew what Carolan’s was and most of the time they left it alone. But there was a price for that. They paid a visit now and again, just to drink Billy’s whiskey and to remind him and his customers they were there on sufferance. And if the Guards wanted information, they got it. A sign behind the bar read: ‘Don’t say anything, Billy’s a fucking unpaid informer’.

That night Vincent Walsh laughed a lot and kept on laughing. He kept on drinking and drank too much, and Billy Donnelly was happy to let him. There were a lot of bad things that could happen to a homosexual man. Falling in love came high on the list. The kind of love that didn’t go away the next time you had sex was the worst. You had to train yourself not to care if you wanted to survive. And behind the laughter Billy could see that Vincent believed in something no one in Carolan’s Bar had any right to believe in. Love was still burning in his eyes. It would be a long time before he let it go. Billy knew. He had been to the same place. Twenty years ago a doctor had pumped his stomach and saved his life. There were days when if he’d met that eejit of a doctor again he’d have beaten the bastard senseless.

It hadn’t been such a bad evening in the end. Carolan’s was at its loud and irreverent best. The sound of laughter and the caramel-brown anaesthetic had numbed Vincent Walsh’s head and put his heart in a box, at least till the morning. They worked hard at laughter in Carolan’s. It was the language in which everyone spoke about everything; politics and the price of bread, sex and family squabbles, memories and dreams, religion and the litter in the streets, joy, sorrow, desire, bitterness, hope, resentment, love, hatred, grief; every ordinary pleasure and irritation that life delivered. Outside they spoke another language. And it was someone else’s tongue. The last recalcitrants were pushed, cajoled and kicked out into the street. Vincent started to pick up pots. The silence was as sobering as the prospect of washing the stinking glasses and emptying out the filthy ashtrays. Billy bolted the door shut.

‘We’ll have the one we came for and let the glasses wash themselves. There won’t be a saint in heaven lifting a finger with the day that’s in it, so why the fecking hell should we?’

Vincent smiled at the comfortable predictability of the words. Every night of Billy Donnelly’s life there was a reason why it was just the wrong time to wash the pots. He had no need of high days and holidays to put off till tomorrow what he was supposed to do today. It was often well into the next afternoon before what passed for clearing up in Carolan’s got underway. If you really wanted a clean glass for a morning pint you were better off bringing your own. But as Billy went behind the bar to twist the cap off another bottle of Bushmills, Vincent carried on collecting glasses. Yes, at some point he would go upstairs to the room in the attic and force himself to go to sleep. Not yet. So Billy poured two more glasses, humming the tuneless tune to himself that always indicated no more conversation was required. Then there was a loud hammering on the front door. Billy sighed, walking across the bar with his most forbidding landlord’s scowl.

‘Now which old queen thinks we can’t get enough of her company?’

He unbolted the door and pulled it open.

‘Didn’t I tell you to piss off –’

He stopped. A tall, thin man in his forties stood in the doorway, smiling amiably. He walked in without a word, followed by three others, a little younger. Under their coats and jackets they all wore the blue shirts that marked them out as members of the Army Comrades Association, demobbed Free State soldiers and assorted hangers-on, who thought they’d knocked the bollocks out of Éamon de Valera in the Civil War, only to see him president of Ireland now. The Blueshirts modelled themselves on the Blackshirts and Brownshirts of Mussolini and Hitler, at least as far as shirts were concerned. Their political agenda hadn’t got any further than brawling with the IRA in the streets, but in the absence of IRA men to pick a fight with, and with drink taken, a bit of Blueshirt queer bashing wouldn’t have been out of the question. Didn’t they pride themselves on defending Ireland’s Catholic values above everything else? But what struck Billy Donnelly immediately was that these Blueshirts weren’t drunk, in fact they were coldly sober.

‘Now, you wouldn’t deny us a drink, Billy, not on a night when we should all be throwing our arms around each other with the holiness of it all. And when it’s starting to rain out there too.’

Billy didn’t know these men, whatever about the familiarity. He glanced back as the last one shut the door and bolted it, smiling. Billy knew that smile; he was a big man who would enjoy what he was going to do.

The older Blueshirt walked across to the bar. He picked up one of the glasses of whiskey Billy had just poured out. He sauntered back towards Vincent. Two of the others went to the bar and started to help themselves to drinks as well. They wouldn’t be sober long. The big man stayed put.

‘And you’re the bum boy. Vincent, is it?’

Vincent didn’t move. He still held a tray of glasses in his hands.

‘You’ve no business in here.’ Billy’s voice was firm. But he was puzzled. He didn’t know why this was happening. If they’d been drunk it would have been easier. He could handle drunks, even queer-bashing drunks. Nine times out of ten they wanted a drink more than they wanted the pleasure of pulping some queers. The thin-faced Blueshirt turned his attention back to Billy. He moved closer to him, pushing him backwards.

‘Were you at the Mass today, Billy?’

Billy said nothing. The man’s easy, conversational tone wouldn’t last. He knew that. He knew what was coming when the man stopped talking.

‘I hear Vincent was. Did you pray for Billy, Vincent? Because the old bugger needs all the prayers he can get. “Quia peccavi nimis cogitatione verbo, et opere: mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.” Right?’ And with each ‘mea culpa’ he slammed his fist into Billy’s chest, forcing him back against the door. ‘Get down on your knees, Billy. Say some prayers.’

Billy was coughing. He was in pain. Vincent took a step towards him but the publican shook his head furiously, choking. The Blueshirt by the door walked over to him. He put both hands on his shoulders and pushed him down hard, till Billy had no choice but to bend his knees and kneel.

‘If we put a white surplice on you, wouldn’t we take you for an altar boy so, Billy boy?’ The thin-faced Blueshirt smiled down at him.

‘The Guards aren’t going to like –’

‘They turn a blind eye to you and your sodomite clan most of the time. That doesn’t mean they wouldn’t think someone had done Dublin a favour if you were floating in the Liffey tomorrow morning. Once in a while you need to be reminded what being a queer is about. Why not now?’

Billy knew, just like Vincent earlier, that there was no reply he could give that wouldn’t provoke more violence. The older man turned to where Vincent still stood with the tray of glasses. He put down the glass of whiskey he was holding, very slowly and very deliberately. It was a simple act, but the very precision with which he placed the glass on the table was menacing.

‘You defiled the Eucharist today. Did I hear it right?’

He stretched out his hand and held Vincent’s wrist in a tight grip.

‘Is that the hand?’

‘I don’t know what you’re on about.’

‘There was a time it would have been cut off for that. I’d do it now.’

Billy was struggling to get up off his knees, determined he would take the beating himself if there had to be one.

‘Jesus and Mary, what is it you bastards want? Get out of here!’

The Blueshirt next to Billy slammed a fist into his stomach. He collapsed on to the floor. The man’s foot came down hard on his chest.

The older Blueshirt still held Vincent’s wrist.

‘A grand day for blackmail was it then, Vincent?’

‘I told you, I don’t know what you’re fucking gabbing about!’

Suddenly the man stopped smiling. He swung Vincent against the wall, knocking the tray of glasses out of his hands. They smashed all around him as he fell to the ground. The Blueshirt bent down and dragged him back up by the throat. Vincent was bleeding. There were cuts on his face, his hands, everywhere. Spots of blood were starting to show through his shirt.

‘All I need is the letters.’

Vincent stared at him. He knew now. It made no sense, but he knew.

‘Do you understand what I’m gabbing about now, bum boy?’

He let go his throat. Vincent leant against a table to get his breath.