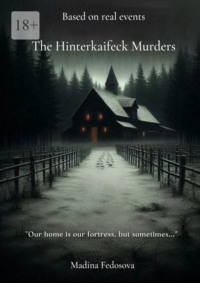

Read the book: «The Hinterkaifeck Murders»

© Madina Fedosova, 2025

ISBN 978-5-0065-9775-4

Created with Ridero smart publishing system

This novel is a fictional interpretation of the unsolved murders that occurred in Hinterkaifeck, Germany, in 1922.

Although the plot is based on historical facts and known details of the case, some characters, relationships, events, and locations have been invented or altered to enhance the narrative and create a gripping thriller.

The author has researched available historical materials and documents related to the Hinterkaifeck case but has, for artistic purposes, deviated from the actual chronology and interpretation of events. It should be regarded as a creative interpretation rather than an accurate account of the tragedy.

The author has strived to treat the memory of the victims with respect and offers sincere condolences to all who have suffered from these tragic events.

The purpose of the novel is not to establish the truth in the Hinterkaifeck case, but to create a work of fiction inspired by real events, and the author hopes that this novel will not cause additional pain or suffering.

Annotation

1922.Hinterkaifeck. Bavaria. A small farm becomes the scene of a tragedy that shocked Germany and went down in history as one of the most brutal and enigmatic crimes of the 20th century. Six people are brutally murdered. The police are baffled. Motives remain unclear. This book is a fictional exploration of the events at Hinterkaifeck, an attempt to understand what really happened and why this crime remains unsolved to this day.

The author, drawing on real facts and evidence, recreates the grim atmosphere of the Bavarian countryside and presents the reader with his version of events. «Our home is our castle,» goes the folk wisdom, but in Hinterkaifeck, it turned into a bloody irony.

Introduction

«The thing about unsolved crimes is that they are never truly solved. They just haven’t been solved yet.» At least, that’s what I tell myself. Perhaps it’s a convenient excuse for the hours I’ve spent studying grainy photographs and yellowed documents, the countless articles and books I’ve read, and the sleepless nights I’ve spent untangling the threads of the Hinterkaifeck mystery. I am not a detective, a historian, or even German. I’m just a writer drawn to the darker sides of the human experience.

But something about this story – the brutal murders on that isolated Bavarian farm, the decades without answers, the sheer, bewildering enigma – has stuck with me. I first stumbled upon this case in an old anthology of true crime, and the details have haunted me ever since. A murdered family, the absence of a clear motive, inexplicable footprints in the snow… it all felt unfinished.

But one thing I know for sure: the story of Hinterkaifeck deserves to be told, and I am here to tell it, to break the silence and present all known facts, striving, as much as possible, for objectivity and respect for the memory of the deceased. To analyze the evidence, to examine the motives, to explore the haunting legacy of a crime that has lingered for years. To grapple with the disturbing questions that continue to plague the minds of those who dare to delve into this story. Whether these lost souls will find peace is another story.

Part One

Premonition

Chapter 1

The Sockets of War

1919—1922

1922.Germany was suffocating in a fetid, post-war haze, poisoned by the acrid ashes of ruined cities and the skeletal shadows of hunger.

Once a proud and mighty empire, whose banners flew over all of Europe, now lay in ruins, like a defeated colossus struck to the heart.

Berlin, which only recently sparkled with lights and teemed with life, had become a labyrinth of debris, where crowds of exhausted and hungry people wandered among the ruins.

A thick smog hung in the air, mixed with the smell of burning and decay. Buildings, like disfigured faces, gaped with the empty sockets of windows, reminiscent of a former beauty mercilessly destroyed by war.

The Treaty of Versailles, like a red-hot brand of shame, seared deep, unhealed scars onto Germany’s ravaged body, humiliatingly restricting the army, seizing its fertile lands, and obligating it to pay unbearable reparations.

And hyperinflation, like an all-consuming fire, rapidly devalued everything, devouring savings, dreams, and hopes, leaving in return only soul-corroding despair.

In once-prosperous cities, where laughter rang and life flourished not long ago, chaos and all-consuming poverty now reigned. The streets filled with throngs of unemployed, yesterday’s soldiers.

Scarred by the war not only physically but also morally, they trudged along the pavement, dragging their mutilated bodies and wounded souls. In their empty eyes, one could read unbearable pain, despair, and a loss of faith in the future.

Medals, received for bravery on the battlefields, now merely clinked uselessly on their tattered uniforms, reminding them of betrayal and oblivion.

They wandered aimlessly through the city in desperate search of any kind of work, any occupation that would allow them to feed their families, or even just a crust of stale bread to quell the excruciating hunger gnawing at them from within.

Many of them, unable to bear the hardships of life, ended their days under bridges and in abandoned houses, dying alone and in poverty, forgotten by everyone except for those as wretched as themselves.

At the newspaper kiosks, the few that had survived the bombings and the economic crisis, dense crowds gathered, eagerly peering at the time-yellowed pages.

Like drowning men, they clung to scraps of news in search of some hope, some explanation for the unfolding nightmare.

Fear, weariness, and despair were etched in their eyes, and their faces were lined with deep wrinkles, like a map of the hardships they had endured.

Each headline, printed in dull font, cut into their consciousness like a red-hot brand, imprinting yet another portion of horror and hopelessness into their memories.

Like sponges, they absorbed every line, every word, trying to understand what awaited them tomorrow, how to survive in this insane world where money had turned to paper and life had been devalued to the extreme.

Berliner Tageblatt Morning Edition, October 18, 1922

Mark Continues to Fall! Bread Riots in Hartmannsdorf District!

Berlin, October 18. (From Our Correspondent) – Alarming news is coming in from all corners of the country. Despite government efforts, the mark continues to plummet, reaching new record lows today. Experts predict further devaluation of the currency, which will inevitably lead to rising prices and a worsening standard of living for the population.

Bread riots have erupted in the Hartmannsdorf district, caused by food shortages and exorbitant prices for essential foodstuffs. Clashes between demonstrators and police have been reported. Authorities are calling for calm, but the situation remains extremely tense.

The Minister of Finance announced today new measures to stabilize the economy, but details of the plan have not yet been disclosed. The opposition is criticizing the government for inaction and demanding the immediate resignation of the cabinet.

Social tensions are also on the rise in Berlin. Cases of robbery and looting have increased. The police have stepped up patrols on the streets but cannot fully control the situation.

The situation in the country remains extremely difficult and requires immediate and decisive action. The Berliner Tageblatt calls on all political forces to join forces to overcome the crisis.

Rheinische Zeitung Evening Edition, October 19, 1922

FAMINE IN THE RUHR REGION: PEOPLE ARE DYING IN THE STREETS!

Essen, October 19. (From Our Correspondent) – The situation in the Ruhr region has reached a catastrophic level. Famine is raging, claiming the lives of dozens, if not hundreds, of people. Mortality has risen sharply, especially among children and the elderly.

Horrifying reports are coming in from the towns and villages of the Ruhr region. People are dying in the streets, in their homes, in queues for meager rations. Corpses are left lying at the scene of death for hours, as the authorities lack the strength and resources to remove them in a timely manner.

«We are facing a real genocide,» said a doctor from Essen in private, who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal. «People are dying of exhaustion, from diseases caused by malnutrition. Children have nothing to eat. Mothers cannot feed their infants. It’s hell on earth.»

Local authorities are appealing for help from the government, but their pleas go unanswered. The government, it seems, is occupied with more important matters than saving the lives of its own citizens. Food supplies are depleted. Prices for bread and other food items have reached exorbitant heights. Smuggling is flourishing.

Meanwhile, the French occupation forces continue to tighten their control over the region, which further exacerbates the situation. The invaders are hindering the delivery of food and coal, condemning the population to suffering and death.

Hartmannische Zeitung calls on all conscientious citizens to take immediate action. It is necessary to organize the collection of funds and food for the starving. It is necessary to put pressure on the government and the occupation authorities to take measures to save people. Time is running out. Every minute of delay costs human lives.

«I saw a woman fall to the ground right in the market square,» says Hans Hartmann, a resident of Bochum. «She was holding an empty basket, from which a few rotten apples fell out. People just walked by. No one stopped to help. Everyone is too busy with themselves.»

«My child died yesterday,» says Frau Schmidt from Dortmund, with tears in her eyes. «He hasn’t eaten for days. He didn’t even have the strength to scream. He just lay there, staring at the ceiling. I don’t know how I can go on living.»

Local authorities are appealing for help from the government, but their pleas go unanswered. Food supplies are depleted. Prices for bread and other food items have reached exorbitant heights. Smuggling is flourishing.

Speculators, hungry for profit, cynically sold essential goods coal for heating, medicine for sick children, a piece of butter for exhausted mothers – at astronomical prices unaffordable to ordinary people.

Crime, like a poisonous weed in an abandoned field, grew at an alarming rate, poisoning an already unbearable life; petty theft, robbery, murder became commonplace, and the corrupt and demoralized police were completely powerless to stop this unrestrained orgy of lawlessness, merely helplessly watching as the country plunged into the abyss of chaos.

One evening, as twilight thickened over Berlin, an old watchmaker named Herr Klaus was returning home after a long day of work.

In his hands, he carried a small bag with the day’s takings – a few marks, barely enough for a loaf of bread and some potatoes for his family. He walked quickly, trying not to attract attention, but his worn-out shoes and patched coat gave him away.

Suddenly, two young men jumped out of a dark alley. Their faces were hidden by dirty rags, and they held shivs made from shards of glass in their hands.

«Stop!» one of them shouted roughly, blocking Herr Klaus’s path. «Your money or your life!»

The old watchmaker, trembling all over, tried to run away, but the second robber grabbed his arm and knocked him to the ground.

«Don’t resist, old man!» hissed the first robber, pressing the shiv to Herr Klaus’s throat. «Give us everything you have!»

«Please…» croaked Herr Klaus, choking with fear. «I have almost nothing… Only enough for food…»

«Don’t lie!» roared the robber, shaking the old man by the shoulders. «We know you have money!»

Herr Klaus, realizing that resistance was useless, handed over the bag of money with trembling hands. The robbers snatched it from his grasp and quickly disappeared into the darkness of the alley.

The old watchmaker lay on the ground, weeping with resentment and helplessness. He knew that his family would now go hungry. But he was alive, and that was the main thing.

Getting to his feet, he slowly trudged home, cursing the war, poverty, and those who had taken away his last hopes.

A particularly oppressive atmosphere hung over the bustling train station, which was normally filled with chaos and commotion.

The smell of coal, machine oil, and human sweat mingled with the pungent odor of disinfectant, a reminder of recent epidemics.

The vast hall, once gleaming with cleanliness and lights, was now dimly lit and covered in a layer of dust and grime.

Exhausted people with extinguished gazes sat on the tattered benches, waiting for their trains, as if for salvation.

In a corner of the hall, a woman was crying, clutching a hungry child to her.

Two men, wrapped in old, tattered coats, stood aside and spoke quietly, waiting for their train. Their faces were hidden by shadows, and their voices were muffled, as if they were afraid of being overheard.

Steam billowed around them from smoking locomotives, creating a sense of unreality.

«Did you hear the news from Munich?» asked one, adjusting his crumpled hat and nervously glancing around the crowd, as if afraid of being heard. «They say there are riots there again. Shooting, barricades…»

«Yes,» replied the other, nervously rubbing his hands and drumming his fingers on a battered briefcase. «This is all not good. They say it’s the communists. Give them free rein, and they’ll turn the whole country into a fire. They’ll get to us soon too.»

He paused for a moment, then lowered his voice: «The main thing is to stay away from politics,» the first advised, and his lips twisted into a semblance of a smile that did not reach his eyes. «And from… the Witch’s Forest. They say it’s unholy there. Locals whisper about strange lights in the night and terrifying cries. Better not to go there.»

The second man nodded, his face paler than usual. In his gaze, fear flickered, mixed with something else – perhaps curiosity, or perhaps a premonition. He glanced towards the exit, as if he wanted to leave this station, permeated with the smell of fear and uncertainty, as soon as possible.

Corpses lay in the streets, and there was no one to take care of their burial. The air was filled with the smell of death and decay.

Chapter 2

Quiet Groben

Groben… The very name seemed to absorb the essence of the place, sounding muffled and down-to-earth, like the whisper of the earth itself, saturated with the scent of damp moss and decaying leaves.

In 1922, when the world around was shaken by wars, revolutions, and economic crises, Groben remained a small, quiet village, lost in the heart of the Bavarian countryside, far from big cities and bustling highways.

As if cut off from the outside world, it was immersed in the greenery of hills and forests, like a child sheltered in its mother’s embrace.

Life here flowed slowly and measuredly, subject not to the bustle of time, but to the natural rhythm of nature and centuries-old traditions passed down from generation to generation.

Time seemed to flow differently here, unhurriedly, like a mountain river carving its way through the stones, leaving behind a trail of peace and tranquility.

In Groben, even under the rays of the bright sun, there was always a shadow, the shadow of long-gone eras, the shadow of great changes that seemed to never reach these secluded places.

Imagine: narrow, winding streets, as if sketched by someone’s careless hand, paved with cobblestones slippery from dew and time. The stones remembered the footsteps of many generations of Groben residents, and each cobblestone held its own story, its own secret.

Along these streets stretched modest but sturdy and well-kept houses, built of wood and stone, with tiled roofs darkened by rain and sun. Each house was unique, with its own character and its own history, but they were all united by one thing – the love and care of their owners.

On the windows and wooden balconies, like bright jewels, boxes and pots with flowers flaunted. Geraniums, petunias, nasturtiums – simple but so dear to the heart flowers, as if competing with each other in brightness and beauty. Every morning, the residents of Groben lovingly cared for their flowers, watering them, trimming dry leaves, and rejoicing in each new bud.

In the mornings, a thick, milky fog rose over the village, like a ghost, enveloping houses and fields, making Groben look like a fabulous, unreal world. Silhouettes of houses and trees barely broke through the fog, creating a sense of mystery and enigma. It seemed that time had stopped, and Groben was frozen in anticipation of something extraordinary.

But then, finally, the first rays of the sun appeared, piercing the fog with their golden arrows. The fog slowly dissipated, exposing Groben in all its glory. Houses, fields, trees – everything was transformed under the rays of the sun, acquiring bright colors and clear contours. And Groben awoke to a new life, filling with the sounds and aromas of a new day. Roosters crowed, cows mooed, dogs barked, coming from the surrounding farms. The air smelled of fresh bread, smoke from chimney flues, and the scent of flowers. Groben lived its life, a life full of work, cares, and hopes.

Most of the inhabitants of Groben were peasants. Their life was inseparable from the land, from sunrise and sunset, from the seasons. Even before the first rays of the sun broke through the morning haze enveloping the valley, the peasants were already getting up. The creak of floorboards, the quiet whisper of a prayer, the sound of water pouring into the washbasin – this is how every day began in a peasant family.

After a meager breakfast consisting of bread and milk, the men went to the fields. Their rough hands, etched with wrinkles and scars, remembered the touch of the earth, of the ears of wheat, of the raw clay. They plowed the land, sowed the grain, harvested the crop – worked from dawn to dusk, knowing no fatigue. Their backs bent under the weight of labor, but their eyes shone with perseverance and hope for a good harvest.

Women remained at home to care for the livestock, cook meals, and look after the children. Their caring hands milked cows, fed pigs, and collected eggs. They washed laundry in cold water, wove linen, and sewed clothes. Their days were filled with chores, but they never complained, knowing that their labor was as important as that of the men.

Some residents of Groben were engaged in crafts. Blacksmiths forged horseshoes, carpenters made furniture, tailors sewed clothes. Their hands skillfully wielded tools, creating beautiful and useful things. Their crafts were passed down from generation to generation, preserving the traditions and culture of Groben.

The life of the peasants was hard and full of worries. Droughts, floods, livestock diseases – all this could suddenly ruin their plans and deprive them of their livelihoods.

But they were strong and hardy people, accustomed to labor and hardship. Nature itself had tempered them, teaching them to appreciate the simple joys of life: the warmth of the hearth, a child’s smile, the taste of fresh bread. They were bound to each other by ties of kinship and friendship, helping each other in difficult times and rejoicing together in successes. Their life, simple and unpretentious, was filled with deep meaning and dignity.

In Groben, as in any other village, there was its church. It was the center of the village’s spiritual life. On Sundays, the residents of Groben gathered in the church to pray and listen to the priest’s sermon. Church holidays were celebrated solemnly and joyfully, with songs, dances, and folk festivities.

In Groben, as in any other self-respecting Bavarian village, a church towered. Not just a building of stone and wood, but the heart of the village, the spiritual center around which the life of every resident revolved.

Its high spire, soaring upwards, was visible from afar, like a beacon pointing the way to lost souls. The church was built many years ago, back in the days of the kings, and within its walls, the prayers of many generations of Groben residents had been heard.

Inside the church, there was an atmosphere of reverence and silence. Sunlight, penetrating through the stained-glass windows, painted the air in soft, muted tones. The smell of incense and old wood filled the space, creating a sense of peace and tranquility. On the walls hung icons of saints, with stern but kind faces, watching over the parishioners.

On Sundays, when the sound of the bells spread throughout the surrounding area, the residents of Groben, dressed in their best clothes, gathered in the church. They came here to pray, to ask forgiveness for their sins, and to receive a blessing for the new week. Their voices, merging into a single choir, rose to the heavens, filling the church with prayers and hymns.

The priest, an old and wise man, read the sermon, talking about love for one’s neighbor, about mercy, and about how to live according to God’s laws. His words resonated in the hearts of the parishioners, strengthening their faith and hope.

Church holidays were celebrated in Groben solemnly and joyfully. The residents of the village dressed in their most beautiful costumes, decorated the church with flowers and ribbons, and organized folk festivities. Songs, dances, games, treats – all this created an atmosphere of joy and unity. All the residents of Groben, from young to old, gathered on the church square to celebrate the holiday together and take a break from the hard workdays. The church, like a caring mother, united all the residents of Groben, giving them faith, hope, and love.

In the village, a little away from the central square, was the school – a small but sturdy building with large windows overlooking the quiet village landscape. Here, every morning, children from Groben and the surrounding farms streamed in, with backpacks on their backs and a gleam of curiosity in their eyes. The school was the pride of the village, a symbol of hope for the future and a place where dreams were born.

The teacher, Mr. Hauser, was a respected man in Groben. Short, thin, with a penetrating gaze and a kind smile, he was not just a teacher, but rather a mentor and guide to the world of knowledge. He knew each student by name, remembered the peculiarities of their character and their dreams. His house, located next to the school, was always open to children and their parents.

The classroom contained wooden desks, covered in ink and etched with carved names. On the walls hung maps, multiplication tables, and portraits of famous Bavarian kings. It smelled of wood, chalk, and fresh ink. Here, in this simple and cozy setting, the children learned the basics of literacy and science.

Mr. Hauser taught the children reading, writing, arithmetic, history, and geography. He told them about faraway lands, about great discoveries, about heroes of the past. He tried not only to impart knowledge but also to develop critical thinking in the children, to teach them to analyze and draw their own conclusions.

But the teacher gave his students not only knowledge. He instilled in them a love for their homeland, for their Bavarian land, for its traditions and culture. He told them about the beauty of their native nature, about the importance of labor, and about the need to respect their elders. He taught them to be honest, just, and merciful.

The school was not only a place of learning but also a place of communication. Here, children found friends, learned to work as a team, shared their joys and sorrows. Here, true friendship was born, which lasted for many years, connecting generations of Groben residents. The school, the teacher, the students – they were all part of one big family, the Groben family, united by love for their land and faith in a bright future.

Chapter 3

The Inn «At the Old Oak»

Inside the inn, it was always noisy and lively. Long wooden tables, roughly hewn, were placed throughout the hall, with peasants, artisans, and merchants sitting at them, sipping beer and exchanging news. In the corner, in front of a large fireplace, firewood crackled, warming the room and creating a cozy atmosphere.

But it wasn’t always peaceful. Sometimes, a rough cry would ring out, and a scuffle would begin. Andreas Gruber, the head of the family from Hinterkaifeck, was not a frequent guest, but when he appeared, the atmosphere changed noticeably. Drunk, irritable, he often found fault with other visitors, insulted them, and provoked them into fights. Hans, the innkeeper, tried to appease him, but Andreas was a stubborn and aggressive man.

«Well, Hans, pour me a mug of your best beer!» shouted a tall, lanky man in a worn leather jacket, sitting down at one of the tables. It was Josef, the local blacksmith.

At the next table, swaying, sat Andreas Gruber himself. His face, usually stern, was flushed from the beer he had drunk. His eyes gleamed with a feverish light, and his lips twisted into a mocking grin. He clutched his glass as if he were afraid it would be taken away from him.

«What’s wrong, men, have you lost heart?» he roared, his voice hoarse from drinking. «Come on, have fun! Drink while you can! Tomorrow, maybe, there won’t be time to drink…» His words hung in the air, like a bad omen.

Fritz, who was playing cards with Günther, glanced at Andreas, trying not to meet his gaze. «Everything’s fine, Andreas,» he muttered, hoping that this would appease Gruber.

But Andreas could not be stopped. «Everything’s fine? And on my farm…”, he stammered, his face contorted with anger, «On my farm, things are happening… Ghosts, at night, wandering around. I hear footsteps, creaks… It’s getting scary!» He laughed, but there was a note of hysteria in his laughter.

Hans, hearing this, frowned. He knew that Andreas was not a simple man. Lately, he had become suspicious, secretive, and had increasingly complained about strange incidents that supposedly took place on his farm.

«Andreas, you should sit at home, rest,» Hans tried to reassure him. «You’ve had too much today, you’ve completely lost your head.»

«Shut up, Hans!» roared Andreas, waving his arms. «It’s none of your business! It’s my life, and I’ll decide what to do!» He splashed the remains of his beer right on the table, causing Fritz and Günther to wince. «And you, cowards, sit here, trembling. Afraid of ghosts? Ha! I have…»

He did not have time to finish speaking when Josef, the blacksmith, rose from the neighboring table. His face, usually calm, was grim. «Andreas, you’re crossing all boundaries today,» he said, his voice firm and confident. «Behave yourself or get out of here.»

«Are you going to tell me what to do, you snot-nosed kid?» Andreas jumped to his feet, his eyes bloodshot. «I’ll show you…»

And then, before he could finish the sentence, he lunged at Josef. A scuffle broke out in the inn. Mugs clattered, chairs flew, shouts and curses were heard. Hans and his wife, Anna, tried to separate the fighters, but Andreas was too strong and fierce. The fight ended only when one of the peasants, seeing that Hans could not cope, dragged Andreas out of the inn, almost throwing him out onto the street. A loud bang of the front door echoed, and silence fell.

The inn became quiet, as if a hurricane had just passed through. People exchanged glances, straightened their clothes, and examined the broken mugs. Hans sighed heavily and began to clean up the aftermath of the fight. Everyone knew that Andreas Gruber was a dangerous man, and this night did not bode well.

A thick silence hung in the air, broken only by the crackling of firewood in the fireplace and the quiet whispers of the visitors. Hans silently swept up the shards of earthenware, his face darker than a thundercloud. Anna, clutching a rag in her hand, carefully wiped beer from the table, trying not to look towards the door behind which Andreas had disappeared.

Josef, the blacksmith, sat at his table, rubbing his bruised jaw. His face was grim, but his gaze was firm. He was not afraid of Andreas, but he understood that this night’s quarrel could have serious consequences. Gruber was a vindictive and vengeful man, and no one knew what he might take it into his head to do.

«So what will happen now?» Fritz asked quietly, turning to Günther. «This Andreas won’t let it go just like that.»

Günther shrugged, his face expressing anxiety. «Who knows what’s on his mind. They say he’s completely lost it.»

«Ghosts or no ghosts, it’s better not to mess with someone like that,» added Josef, interrupting their conversation. «We have to be careful. Especially those who live next to his farm.»

Hans, finishing cleaning up, approached their table, his face serious. «Josef, you’re right,» he said. «This Andreas has completely lost his head. I wouldn’t be surprised if he does something terrible. We have to report to the sheriff.»

«And what will the sheriff do?» Fritz scoffed skeptically. «Andreas is a rich farmer, he’ll always find a way to buy his way out. And then we’ll have to live with it…»

«Nevertheless, we have to do something,» Hans insisted. «We can’t keep silent. Otherwise, trouble can’t be avoided.»

But, as is often the case in small villages, fear and distrust prevailed over a sense of duty. No one wanted to interfere, no one wanted to incur the wrath of Andreas Gruber. Everyone preferred to pretend that nothing had happened, hoping that the storm would pass them by.

And outside the window, in the night darkness, stood the old oak, a witness to many generations of Groben residents. Its branches, like bony fingers, reached towards the sky, and its leaves rustled, as if whispering words of warning. But no one heard them.

Soon, the inn «At the Old Oak» was filled with noise and fun again. The musicians played a new melody, people began to dance, and life seemed to return to normal. But beneath the mask of merriment hid fear and anxiety. Everyone felt that something was wrong, that a dark shadow hung over Groben, which was soon to engulf this quiet and peaceful corner of Bavaria.