This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

Read the book: «My Dark Vanessa»

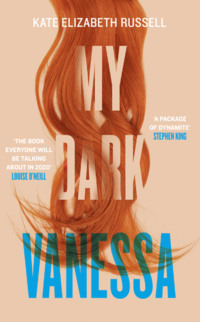

My Dark Vanessa

KATE ELIZABETH RUSSELL

Copyright

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020

Copyright © Kate Elizabeth Russell 2020

Kate Elizabeth Russell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008342241

Ebook Edition © January 2020 ISBN: 9780008342265

Version: 2019-10-22

Dedication

For the real-life Dolores Hazes and Vanessa Wyes whose stories have not yet been heard, believed, or understood

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

2017

2000

2017

2000

2017

2001

2017

2001

2017

2001

2017

2002

2017

2006

2017

2007

2017

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

2017

I get ready for work and the post has been up for eight hours. While curling my hair, I refresh the page. So far, 224 shares and 875 likes. I put on my black wool suit, refresh again. I dig under the couch for my black flats, refresh. Fasten the gold name tag to my lapel, refresh. Each time, the numbers climb and the comments multiply.

You’re so strong.

You’re so brave.

What kind of monster could do that to a child?

I bring up my last text, sent to Strane four hours ago: So, are you ok …? He still hasn’t responded, hasn’t even read it. I type out another—I’m here if you want to talk—then think better and delete it, send instead a wordless line of question marks. I wait a few minutes, try calling him, but when the voicemail kicks in, I shove my phone in my pocket and leave my apartment, yanking the door closed behind me. There’s no need to try so hard. He created this mess. It’s his problem, not mine.

At work, I sit at the concierge desk in the corner of the hotel lobby and give guests recommendations on where to go and what to eat. It’s the tail end of the busy season, the last few tourists passing through to see the foliage before Maine closes up for the winter. With an unwavering smile that doesn’t quite reach my eyes, I make a dinner reservation for a couple celebrating their first anniversary and arrange for a bottle of champagne to be waiting in their room upon return, a gesture that goes above and beyond, the kind of thing that will earn me a good tip. I call the town car to drive a family to the jetport. A man who stays at the hotel every other Monday night on business brings me three soiled shirts, asks if they can be dry-cleaned overnight.

“I’ll take care of it,” I say.

The man grins, gives me a wink. “You’re the best, Vanessa.”

On my break, I sit in an empty cubicle in the back office, staring at my phone as I eat a day-old sandwich left over from a catered event. Checking the Facebook post is compulsive now; I can’t stop my fingers from moving or my eyes from darting across the screen, taking in the rising likes and shares, the dozens of you’re fearless, keep telling your truth, I believe you. Even as I read, three dots flash—someone is typing a comment right this second. Then, like magic, another appears, another message of strength and support that makes me slide my phone across the desk and toss the rest of the stale sandwich in the trash.

I’m about to head back out into the lobby when my phone begins to vibrate: INCOMING CALL JACOB STRANE. I laugh as I answer, relieved he’s alive, that he’s calling. “Are you ok?”

For a moment, there’s only dead air and I freeze, my eyes fixed on the window that looks out on Monument Square, the autumn farmers’ market and food trucks. It’s the beginning of October, full-blown fall, the time when everything in Portland appears straight out of an L.L.Bean catalog—pumpkins and gourds, jugs of apple cider. A woman in plaid flannel and duck boots crosses the square, smiling down at the baby strapped to her chest.

“Strane?”

He exhales a heavy sigh. “I guess you saw.”

“Yeah,” I say. “I saw.”

I don’t ask questions, but he launches into an explanation anyway. He says the school is opening an investigation and he’s bracing himself for the worst. He assumes they’ll force him to resign. He doubts he’ll make it through the school year, maybe not even to Christmas break. Hearing his voice is such a shock that I struggle to keep up with what he says. It’s been months since we last spoke, when I was gripped with panic after my dad died of a heart attack and I told Strane I couldn’t do it anymore; the same sudden onset of morals I’ve had through years of screwups—lost jobs, breakups, and breakdowns—as though being good could retroactively fix all the things I’ve broken.

“But they already investigated back when she was your student,” I say.

“They’re revisiting it. Everyone’s getting interviewed all over again.”

“If they decided you didn’t do anything wrong back then, why would they change their minds now?”

“Paid any attention to the news lately?” he asks. “We’re living in a different time.”

I want to tell him he’s being overdramatic, that it’ll be ok so long as he’s innocent, but I know he’s right. For the past month, something’s been gaining momentum, a wave of women outing men as harassers, assaulters. It’s mostly celebrities who have been targeted—musicians, politicians, movie stars—but less famous men have been named, too. No matter their background, the accused go through the same steps. First, they deny everything. Then, as it becomes clear the din of accusations isn’t going away, they resign from their jobs in disgrace and issue a statement of vague apology that stops short of admitting wrongdoing. Then the final step: they go silent and disappear. It’s been surreal to watch it play out day after day, these men falling so easily.

“It should be ok,” I say. “Everything she wrote is a lie.”

On the phone, Strane sucks in a breath, air whistling through his teeth. “I don’t know if she is lying, at least not technically.”

“But you barely touched her. In that post, she says you assaulted her.”

“Assault,” he scoffs. “Assault can be anything, like how battery can mean you grabbed someone by the wrist or shoved their shoulder. It’s a meaningless legal term.”

I stare out the window at the farmers’ market: the milling crowd, the swarming seagulls. A woman selling food opens a metal tub, releasing a cloud of steam as she pulls out two tamales. “You know, she messaged me last week.”

A beat of silence. “Did she.”

“She wanted to see if I’d come forward, too. Probably figured she’d be more believable if she roped me into it.”

Strane says nothing.

“I didn’t respond. Obviously.”

“Right,” he says. “Of course.”

“I thought she was bluffing. Didn’t think she’d have the nerve.” I lean forward, press my forehead against the window. “It’ll be ok. You know where I stand.”

And with that, he breathes out. I can imagine the smile of relief on his face, the creases in the corners of his eyes. “That’s all I need to hear,” he says.

Back at the concierge desk, I bring up Facebook, type “Taylor Birch” in the search bar, and her profile fills the screen. I scroll through the sparse public content I’ve scrutinized for years, the photos and life updates, and now, at the top, the post about Strane. The numbers still climb—438 shares now, 1.8k likes, plus new comments, more of the same.

This is so inspiring.

I’m in awe of your strength.

Keep speaking your truth, Taylor.

When Strane and I met, I was fifteen and he was forty-two, a near perfect thirty years between us. That’s how I described the difference back then—perfect. I loved the math of it, three times my age, how easy it was to imagine three of me fitting inside him: one of me curled around his brain, another around his heart, the third turned to liquid and sliding through his veins.

At Browick, he said, teacher-student romances were known to happen from time to time, but he’d never had one because, before me, he’d never had the desire. I was the first student who put the thought in his head. There was something about me that made it worth the risk. I had an allure that drew him in.

It wasn’t about how young I was, not for him. Above everything else, he loved my mind. He said I had genius-level emotional intelligence and that I wrote like a prodigy, that he could talk to me, confide in me. Lurking deep within me, he said, was a dark romanticism, the same kind he saw within himself. No one had ever understood that dark part of him until I came along.

“It’s just my luck,” he said, “that when I finally find my soul mate, she’s fifteen years old.”

“If you want to talk about luck,” I countered, “try being fifteen and having your soul mate be some old guy.”

He checked my face after I said this to make sure I was joking—of course I was. I wanted nothing to do with boys my own age, their dandruff and acne, how cruel they could be, cutting girls up into features, rating our body parts on a scale of one to ten. I wasn’t made for them. I loved Strane’s middle-aged caution, his slow courtship. He compared my hair to the color of maple leaves, slipped poetry into my hands—Emily, Edna, Sylvia. He made me see myself as he did, a girl with the power to rise with red hair and eat him like air. He loved me so much that sometimes after I left his classroom, he lowered himself into my chair and rested his head against the seminar table, trying to breathe in what was left of me. All of that happened before we even kissed. He was careful with me. He tried so hard to be good.

It’s easy to pinpoint when it all started, that moment of walking into his sun-soaked classroom and feeling his eyes drink me in for the first time, but it’s harder to know when it ended, if it really ended at all. I think it stopped when I was twenty-two, when he said he needed to get himself together and couldn’t live a decent life while I was within reach, but for the past decade there have been late-night calls, him and me reliving the past, worrying the wound we both refuse to let heal.

I assume I’ll be the one he turns to in ten or fifteen years, whenever his body begins to break down. That seems the likely ending to this love story: me dropping everything and doing anything, devoted as a dog, as he takes and takes and takes.

I get out of work at eleven and move through the empty downtown streets, counting each block I walk without checking Taylor’s post as a personal victory. In my apartment, I still don’t look at my phone. I hang up my work suit, take off my makeup, smoke a bowl in bed, and turn off the light. Self-control.

But in the dark, something shifts within me as I feel the bedsheets slide across my legs. Suddenly, I’m full of need—to be reassured, to hear him say, plainly, that of course he didn’t do what that girl says he did. I need him to say again that she’s lying, that she was a liar ten years ago and is a liar still, taken in now by the siren song of victimhood.

He answers halfway through the first ring, as though expecting me to call. “Vanessa.”

“I’m sorry. I know it’s late.” I balk then, unsure how to ask for what I want. It’s been so long since we last did this. My eyes travel the dark room, taking in the outline of the open closet door, the streetlight shadow across the ceiling. Out in the kitchen, the refrigerator hums and the faucet drips. He owes me this, for my silence, my loyalty.

“I’ll be quick,” I say. “Just a few minutes.”

There’s the rustle of blankets as he sits up in bed and moves the phone from one ear to the other, and for a moment I think he’s about to say no. But then, in the half whisper that turns my bones to milk, he begins to tell me what I used to be: Vanessa, you were young and dripping with beauty. You were teenage and erotic and so alive, it scared the hell out of me.

I turn onto my stomach and shove a pillow between my legs. I tell him to give me a memory, something I can slip into. He’s quiet as he flips through the scenes.

“In the office behind the classroom,” he says. “It was the dead of winter. You, laid out on the sofa, your skin all goose bumps.”

I close my eyes and I’m in the office—white walls and gleaming wood floors, the table with a pile of ungraded papers, a scratchy couch, a hissing radiator, and a single window, octagonal with glass the color of seafoam. I’d fix my eyes on it while he worked at me, feeling underwater, my body weightless and rolling, not caring which way was up.

“I was kissing you, going down on you. Making you boil.” He lets out a soft laugh. “That’s what you used to call it. ‘Make me boil.’ Those funny phrases you’d come up with. You were so bashful, hated talking about any of it, just wanted me to get on with it. Do you remember?”

I don’t remember, not exactly. So many of my memories from back then are shadowy, incomplete. I need him to fill in the gaps, though sometimes the girl he describes sounds like a stranger.

“It was hard for you to keep quiet,” he says. “You used to bite your mouth shut. I remember once you bit down on your bottom lip so hard, you started to bleed, but you wouldn’t let me stop.”

I press my face into the mattress, grind myself against the pillow as his words flood my brain and transport me out of my bed and into the past where I’m fifteen and naked from the waist down, sprawled on the couch in his office, shivering, burning, as he kneels between my legs, his eyes on my face.

My god, Vanessa, your lip, he says. You’re bleeding.

I shake my head and dig my fingers into the cushions. It’s fine, keep going. Just get it over with.

“You were so insatiable,” Strane says. “That firm little body.”

I breathe hard through my nose as I come, as he asks me if I remember how it felt. Yes, yes, yes. I remember that. The feelings are what I’ve been able to hold on to—the things he did to me, how he always made my body writhe and beg for more.

I’ve been seeing Ruby for eight months, ever since my dad died. At first it was grief therapy, but it’s turned into talking about my mom, my ex-boyfriend, how stuck I feel in my job, how stuck I feel about everything. It’s an indulgence, even with Ruby’s sliding scale—fifty bucks a week just to get someone to listen to me.

Her office is a couple blocks from the hotel, a softly lit room with two armchairs, a sofa, and end tables holding boxes of tissues. The windows look out at Casco Bay: gulls swarming above the fishing piers, slow-moving oil tankers, and amphibious duck tours that quack as they ease into the water and transform from bus to boat. Ruby is older than me, big-sister older rather than mom older, with dishwater blond hair and granola clothes. I love her wooden-heeled clogs, the clack-clack-clack they make as she walks across her office.

“Vanessa!”

I love, too, the way she says my name as she opens the door, like she’s relieved to see me standing there and not anyone else.

That week we talk about the prospect of me going home for the upcoming holidays, the first without Dad. I’m worried my mother is depressed and don’t know how to broach the subject. Together, Ruby and I come up with a plan. We go through scenarios, the likely ways Mom will respond if I suggest she might need help.

“As long as you approach it with empathy,” Ruby says, “I think you’ll be ok. You two are close. You can handle talking about hard stuff.”

Close with my mother? I don’t argue but don’t agree. Sometimes I marvel at how easily I deceive people, doing it without even trying.

I manage to hold off checking the Facebook post until the end of the session, when Ruby takes out her phone to enter our next appointment into her calendar. Glancing up, she catches my furious scroll and asks if there’s any breaking news.

“Let me guess,” she says, “another abuser exposed.”

I look up from my phone, my limbs cold.

“It’s just so endless, isn’t it?” She gives a sad smile. “There’s no escape.”

She starts talking about the latest high-profile exposé, a director who built a career out of films about women being brutalized. Behind the scenes of those films, he apparently enjoyed exposing himself to young actresses and cajoling them into giving him blow jobs.

“Who would have guessed that guy was abusive?” Ruby asks, sarcastic. “His movies are all the evidence we need. These men hide in plain sight.”

“Only because we let them,” I say. “We all turn a blind eye.”

She nods. “You’re so right.”

It’s thrilling to talk like this, to creep so close to the edge.

“I don’t know what to think of all the women who worked with him over and over,” I say. “Did they have no self-respect?”

“Well, you can’t blame the women,” Ruby says. I don’t argue, just hand her my check.

At home I get stoned and fall asleep on the couch with all the lights on. At seven in the morning, my phone buzzes against the hardwood floor with a text and I stumble across the room for it. Mom. Hi honey. Just thinking of you.

Staring at the screen, I try to gauge what she knows. Taylor’s Facebook post has been up for three days now, and though Mom isn’t connected with anyone from Browick, the post has been shared so widely. Besides, she’s online all the time these days, endlessly liking, sharing, and getting into fights with conservative trolls. She easily could have seen it.

I minimize the text and bring up Facebook: 2.3k shares, 7.9k likes. Last night, Taylor posted a public status update:

BELIEVE WOMEN.

2000

Turning onto the two-lane highway that takes us to Norumbega, Mom says, “I really want you to get out there this year.”

It’s the start of my sophomore year of high school, dorm move-in day, and this drive is Mom’s last chance to hold me to promises before Browick swallows me whole and her access to me is limited to phone calls and school breaks. Last year, she worried boarding school might make me wild, so she made me promise not to drink or have sex. This year, she wants me to promise I’ll make new friends, which feels exponentially more insulting, maybe even cruel. My falling-out with Jenny was five months ago, but it’s still raw. The mere phrase “new friends” twists my stomach; the idea feels like betrayal.

“I just don’t want you sitting alone in your room day and night,” she says. “Is that so bad?”

“If I were home, all I’d do is sit in my room.”

“But you’re not at home. Isn’t that the point? I remember you saying something about a ‘social fabric’ when you convinced us to let you come here.”

I press myself into the passenger seat, wishing my body could sink into it entirely so I wouldn’t have to listen to her use my own words against me. A year and a half ago, when a Browick representative came to my eighth grade class and played a recruitment video featuring a manicured campus bathed in golden light and I started the process of convincing my parents to let me apply, I made a twenty-point list entitled “Reasons Why Browick Is Better Than Public School.” One of the points was the “social fabric” of the school, along with the college acceptance rate among graduates, the number of AP course offerings, things I’d picked up from the brochure. In the end, I needed only two points to convince my parents: I earned a scholarship so it wouldn’t cost them money, and the Columbine shooting happened. We spent days watching CNN, the looped clips of kids running for their lives. When I said, “Something like Columbine would never happen at Browick,” my parents exchanged a look, like I’d vocalized what they’d already been thinking.

“You moped all summer,” Mom says. “Now it’s time to shake it off, move on with your life.”

I mumble, “That isn’t true,” but it is. If I wasn’t spaced out in front of the television, I was sprawled in the hammock with my headphones on, listening to songs guaranteed to make me cry. Mom says dwelling in your feelings is no way to live, that there will always be something to be upset about and the secret to a happy life is not to let yourself be dragged down into negativity. She doesn’t understand how satisfying sadness can be; hours spent rocking in the hammock with Fiona Apple in my ears make me feel better than happy.

In the car, I shut my eyes. “I wish Dad had come so you wouldn’t talk to me like this.”

“He’d tell you the same thing.”

“Yeah, but he’d be nicer about it.”

Even with my eyes closed, I can see everything that passes by the windows. It’s only my second year at Browick, but we’ve made this drive at least a dozen times. There are the dairy farms and rolling foothills of western Maine, general stores advertising cold beer and live bait, farmhouses with sagging roofs, collections of rusted car scraps in yards of waist-high grass and goldenrod. Once you enter Norumbega, it becomes beautiful—the perfect downtown, the bakery, the bookstore, the Italian restaurant, the head shop, the public library, and the hilltop Browick campus, gleaming white clapboard and brick.

Mom turns the car into the main entrance. The big BROWICK SCHOOL sign is decorated with maroon and white balloons for move-in day, and the narrow campus roads are crammed with cars, overstuffed SUVs parked haphazardly, parents and new students wandering around, gazing up at the buildings. Mom sits forward, hunched over the steering wheel, and the air between us tightens as the car lurches forward, then halts, lurches again.

“You’re a smart, interesting kid,” she says. “You should have a big group of friends. Don’t get sucked into spending all your time with just one person.”

Her words are harsher than she probably means them to be, but I snap at her anyway. “Jenny wasn’t just some person. She was my roommate.” I say the word as though the significance of the relationship should be obvious—its disorienting closeness, how it could sometimes turn the world beyond the shared room muted and pale—but Mom doesn’t get it. She never lived in a dorm, never went to college, let alone boarding school.

“Roommate or not,” she says, “you could’ve had other friends. Focusing on a single person isn’t the healthiest, that’s all I’m saying.”

In front of us, the line of cars splits as we approach the campus green. Mom flips on the left blinker, then the right. “Which way am I going here?”

Sighing, I point to the left.

Gould is a small dorm, really just a house, with eight rooms and one dorm parent apartment. Last year I drew a low number in the housing lottery, so I was able to get a single, rare for a sophomore. It takes Mom and me four trips to move in all my stuff: two suitcases of clothes, a box of books, extra pillows and bedsheets and a quilt she made of old T-shirts I’d outgrown, a pedestal fan we set up to oscillate in the center of the room.

While we unpack, people pass by the open door—parents, students, someone’s younger brother who sprints up and down the hallway until he trips and starts to wail. At one point, Mom goes to the bathroom and I hear her say hello in her fake-polite voice, then another mother’s voice says hello back. I stop stacking books on the shelf above my desk to listen. Squinting, I try to place the voice—Mrs. Murphy, Jenny’s mom.

Mom comes back into the room, pulls the door shut. “Getting kind of noisy out there,” she says.

Sliding books onto the shelf, I ask, “Was that Jenny’s mom?”

“Mm-hmm.”

“Did you see Jenny?”

Mom nods but doesn’t elaborate. For a while, we unpack in silence. As we make the bed, pulling the fitted sheet over the pin-striped mattress, I say, “Honestly, I feel sorry for her.”

I like how it sounds, but of course it’s a lie. Just last night, I spent an hour scrutinizing myself in my bedroom mirror, trying to see myself as Jenny would, wondering if she’d notice my hair lightened from Sun In, the new hoops in my ears.

Mom says nothing as she lifts the quilt out of a plastic tote. I know she’s worried I’ll backtrack, end up heartbroken again.

“Even if she tried to be friends with me now,” I say, “I wouldn’t waste my time.”

Mom smiles thinly, smoothing the quilt over the bed. “Is she still dating that boy?” She means Tom Hudson, Jenny’s boyfriend, the catalyst for the falling-out. I shrug like I don’t know, but I do. Of course I do. All summer I checked Jenny’s AOL profile and her relationship status never changed from “Taken.” They’re still together.

Before she leaves, Mom gives me four twenties and makes me promise to call home every Sunday. “No forgetting,” she instructs. “And you’re coming home for Dad’s birthday.” She hugs me so hard it hurts my bones.

“I can’t breathe.”

“Sorry, sorry.” She puts on her sunglasses to hide her teary eyes. On her way out of the dorm room, she points a finger at me. “Be good to yourself. And be social.”

I wave her off. “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” From my doorway, I watch her walk down the hallway, disappear into the stairwell, and then she’s gone. Standing there, I hear two approaching voices, the bright echoing laughter of mother and daughter. I duck into the safety of my room as they appear, Jenny and her mother. I catch only a glimpse, just long enough to see that her hair is shorter and she’s wearing a dress I remember hanging in her closet all last year but never saw her wear.

Lying back on my bed, I let my eyes wander the room and listen to the goodbyes in the hallway, the sniffles and quiet cries. I think back to a year ago, moving into the freshman dorm, the first night of staying up late with Jenny while the Smiths and Bikini Kill played from her boom box, bands I’d never heard of but pretended to know because I was scared to out myself as a loser, a bumpkin. I worried if I did, she wouldn’t like me anymore. During those first few days at Browick, I wrote in my journal, The thing I love most about being here is that I get to meet people like Jenny. She is so freaking COOL and just being around her is teaching me how to be cool, too! I’d since torn out that entry, thrown it away. The sight of it made my face burn with shame.

The dorm parent in Gould is Ms. Thompson, the new Spanish teacher, fresh out of college. During the first night meeting in the common room, she brings colored markers and paper plates for us to make name tags for our doors. The other girls in the dorm are upperclassmen, Jenny and I the only sophomores. We give each other plenty of space, sitting on opposite ends of the table. Jenny hunches over as she makes her name tag, her brown bobbed hair falling against her cheeks. When she comes up for air and to switch markers, her eyes skim over me as though I don’t even register.

“Before you go back to your rooms, go ahead and take one of these,” Ms. Thompson says. She holds open a plastic bag. At first, I think it is candy, then see it’s a pile of silver whistles.

“Chances are you won’t ever need to use these,” she says, “but it’s good to have one, just in case.”

“Why would we need a whistle?” Jenny asks.

“Oh, you know, just a campus safety measure.” Ms. Thompson smiles so wide I can tell she’s uncomfortable.

“But we didn’t get these last year.”

“It’s in case someone tries to rape you,” Deanna Perkins says. “You blow the whistle to make him stop.” She brings a whistle to her lips and blows hard. The sound rings through the hallway, so satisfyingly loud we all have to try.

Ms. Thompson attempts to talk over the din. “Ok, ok.” She laughs. “I guess it’s good to make sure they work.”

“Would this seriously stop someone if he wanted to rape you?” Jenny asks.

“Nothing can stop a rapist,” Lucy Summers says.

“That’s not true,” Ms. Thompson says. “And these aren’t ‘rape’ whistles. They’re a general safety tool. If you’re ever feeling uncomfortable on campus, you just blow.”

“Do the boys get whistles?” I ask.

Lucy and Deanna roll their eyes. “Why would boys need a whistle?” Deanna asks. “Use your brain.”

At that Jenny laughs loud, as though Lucy and Deanna weren’t just rolling their eyes at her.

It’s the first day of classes and the campus is bustling, clapboard buildings with their windows thrown open, the staff parking lots full. At breakfast I drink black tea while perched at the end of a long Shaker-style table, my stomach too knotted to eat. My eyes dart around the cathedral-ceilinged dining hall, taking in new faces and the changes in familiar ones. I notice everything about everyone—that Margo Atherton parts her hair on the left to hide her lazy right eye, that Jeremy Rice steals a banana from the dining hall every single morning. Even before Tom Hudson started going out with Jenny, before there was a reason to care about anything he did, I’d noticed the exact rotation of band T-shirts he wore under his button-downs. It’s both creepy and out of my control, this ability I have to notice so much about other people when I’m positive no one notices anything at all about me.