This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

Read the book: «What Makes Women Happy»

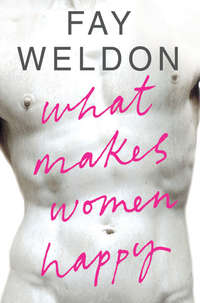

What Makes Women Happy

Fay Weldon

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

ONE Sources of Happiness

Sex

Food

Friends

Family

Shopping

Chocolate

TWO Saints and Sinners

Death: The Gates of Paradise

Bereavement: Unseating the Second Horseman

Loneliness: Unseating the Third Horseman

Shame: Unseating the Fourth Horseman

Something Here Inside

Also by Fay Weldon

Copyright

About The Publisher

ONE Sources of Happiness

Women can be wonderfully happy. When they’re in love, when someone gives them flowers, when they’ve finally found the right pair of shoes and they even fit. I remember once, in love and properly loved, dancing round a room singing, ‘They can’t take this away from me.’ I remember holding the green shoes with the green satin ribbon (it was the sixties) to my bosom and rejoicing. I remember my joy when the midwife said, ‘But this is the most beautiful baby I’ve ever seen. Look at him, he’s golden!’

The wonderful happiness lasts for ten minutes or so. After that little niggles begin to arise. ‘Will he think I’m too fat?’ ‘Are the flowers his way of saying goodbye?’ ‘Do the shoes pinch?’ ‘Will his allegedly separated wife take this away from me?’ ‘Is solitary dancing a sign of insanity?’ ‘How come I’ve produced so wonderful a baby – did they get the name tags wrong?’

Anxiety and guilt come hot on the heels of happiness. So the brutal answer to what makes women happy is ‘Nothing, not for more than ten minutes at a time.’ But the perfect ten minutes are worth living for, and the almost perfect hours that circle them are worth fighting for, and examining, the better to prolong them.

Ask women what makes them happy and they think for a minute and come up with a tentative list. It tends to run like this, and in this order:

Sex

Food

Friends

Family

Shopping

Chocolate

‘Love’ tends not to get a look in. Too unfashionable, or else taken for granted. ‘Being in love’ sometimes makes an appearance. ‘Men’ seem to surface as a source of aggravation, and surveys keep throwing up the notion that most women prefer chocolate to sex. But personally I suspect this response is given to entertain the pollsters. The only thing you can truly know about what people think, feel, do and consume, some theorize, is to examine the contents of their dustbins. Otherwise it’s pretty much guesswork.

There are more subtle pleasures too, of course, which the polls never throw up. The sense of virtue when you don’t have an éclair can be more satisfactory than the flavour and texture of cream, chocolate and pastry against the tongue. Rejecting a lover can give you more gratification than the physical pleasures of love-making. Being right when others are wrong can make you very happy indeed. We’re not necessarily nice people.

Some women I know always bring chocolates when they’re invited to dinner – and then sneer when the hostess actually eats one. That’s what I mean by ‘not nice’.

Sources of Unhappiness

We are all still creatures of the cave, although we live in loft apartments. Nature is in conflict with nurture. Anxiety and guilt cut in to spoil the fun as one instinct wars with another and with the way we are socialized. Women are born to be mothers, though many of us prefer to not take up the option. The baby cries; we go. The man calls; ‘Take me!’ we cry. Unless we are very strong indeed, physiology wins. We bleed monthly and the phases of the moon dictate our moods. We are hardwired to pick and choose amongst men when we are young, aiming for the best genetic material available. The ‘love’ of a woman for a man is nature’s way of keeping her docile and at home. The ‘love’ of a man for a woman is protective and keeps him at home as long as she stays helpless. (If high-flying women, so amply able to look after themselves, are so often single, it can be no surprise.)

Or that is one way of looking at it. The other is to recognize that we are moral creatures too, long for justice, and civilized ourselves out of our gross species instincts long ago. We like to think correctly and behave in an orderly and socially aware manner. If sometimes we revert, stuff our mouths with goodies, grab what we can so our neighbour doesn’t get it (‘Been to the sales lately?’) or fall upon our best friend’s boyfriend when left alone in the room with him, we feel ashamed of ourselves. Doing what comes naturally does not sit well with modern woman.

And so it is that in everyday female life, doubts, dilemmas and anxieties cut in, not grandiose whither-mankind stuff, just simple things such as:

Sex: ‘Should I have done it?’

Food: ‘Should I have eaten it?’

Friends/family: ‘Why didn’t I call her?’

Shopping: ‘Should I have bought it?’

Chocolate: ‘My God, did I actually eat all that?’

But you can’t lie awake at night worrying about these things. You have to get up in the morning and work, so you do. But the voice of conscience, otherwise known as the voice of guilt, keeps up its nagging undercurrent. It drives some women to therapists in their attempt to silence it. But it’s better to drive into a skid than try to steer out of it. If you don’t want to feel guilty, don’t do it. If you want to be happy, try being good.

What Makes Men Happy

Men have their own list when it comes to sources of happiness. ‘The love of a good woman’ is high in the ratings. Shopping and chocolate don’t get much of a look in. Watching porn and looking at pretty girls in the street, if men are honest, feature large. These fondnesses of theirs (dismissed by women as ‘addictions’) can make women unhappy, break up marriages and make men wretched and secretive because the women they love get upset by them.

Women should not be upset. They should not expect men to behave like women. Men are creatures of the cave too. Porn is sex in theory, not in practice. It just helps a man get through the day. And many a woman too, come to that.

Porn excites to sex, sure. Sex incited by porn is not bad, just different. Tomorrow’s sex is always going to be different from today’s. In a long-term partnership there is room and time for all kinds. Sex can be tender, loving, companionable, a token of closeness and respect, the kind women claim to like. Then it’s romantic, intimate, and smacks of permanence. Sometimes sex is a matter of lust, release, excitement, anger, and the sense is that any woman could inspire it. It’s macho, anti-domestic. Exciting. Don’t resist the mood – try and match it. Tomorrow something else will surface more to your liking. Each sexual act will have a different feel to it, the two instincts in both of you being in variable proportions from night to night, week to week, year to year. It’s rare for a couple’s sexual energies to be exactly matched. But lucky old you if they are.

I have friends so anxious that they can’t let the man in their life out of their sight in case he runs off with someone else. It’s counter-productive. Some girls just do stop traffic in the street. So it’s not you – so what? Men like looking at pretty girls in the street not because they long to sleep with them, or because given a choice between them and you they’d choose them, but because it’s the instinct of the cave asserting itself. Pretty girls are there to be looked at speculatively by men and, if they have any sense, with generous appreciation by women. It’s bad manners in men, I grant you, to do it too openly, especially if the woman objects, but not much worse than that.

This will not be enough, I know, to convince some women that for a husband or lover to watch porn is not a matter for shock-horror. But look at it like this. A newborn baby comes into the world with two urgent appetites: one is to feed, the other is to suck. Because the nipple is there to satisfy both appetites, the feeding/sucking distinction gets blurred for both mother and baby. If you are lucky, the baby’s time at the breast or bottle is time enough to satisfy the sucking instinct. If you’re not lucky, the baby, though fed to completion, cries, chafes and vomits yet goes on sucking desperately, as if it were monstrously hungry. At which point the wise mother goes to fetch a dummy, so everyone can get some peace. Then baby can suck, digest and sleep, all at the same time, blissfully. (Most babies simply toss the dummy out of the cot as soon as they’re on solids and the sucking reflex fades, thus sparing the mother social disgrace.)

In the same way, in males, the instinct for love and the need for sexual gratification overlap but do not necessarily coincide. The capacity for love seems inborn; lust weighs in powerfully at puberty. The penis is there to satisfy both appetites. If you are lucky, the needs coincide in acts of domestic love; if you are not, your man’s head turns automatically when a pretty girl passes in the street, or he goes to the porn channels on the computer. He is not to be blamed. Nor does it affect his relationship with you. Love is satisfied, sex isn’t quite. He clutches the dummy.

An Unreliable Narrator

Bear in mind, of course, that you must take your instruction from a very flawed person. She wouldn’t want to make you anxious by being perfect. Your writer spent last night in the spare room following a domestic row. Voices were raised, someone broke a glass, she broke the washing machine by trying to wrench open the door while it was in the middle of its spin cycle.

Domestic rows do not denote domestic unhappiness. They do suggest a certain volatility in a relationship. Sense might suggest that if the morning wakes to the lonely heaviness that denotes a row the night before, you have no business describing your marriage as ‘happy’. But sense and experience also suggest that you have made your own contribution to the way you now feel. And the early sun beats in the windows and it seems an insult to your maker to maintain a grudge when the morning is so glorious.

You hear the sound of the vacuum cleaner downstairs. Soon it will be safe to go down and have a companionable breakfast without even putting on your shoes for fear of slivers of broken glass. Storms pass, the sun shines again. Yes, you are happy.

What the quarrel was about I cannot for the life of me remember.

Except of course now the washing machine doesn’t work. When it comes to domestic machinery, retribution comes fast. In other areas of life it may come slowly. But it always does come, in terms of lost happiness, in distance from heaven, in the non-appearance of angels.

And since this book comes to your writer through the luminiferous aether, that notoriously flimsy and deceptive substance, Victorian equivalent of the dark matter of which scientists now claim the universe is composed, what is said is open to interpretation. It is not the Law.

Why, Why?

Like it or not, we are an animal species. Darwinian principles apply. We have evolved into what we are today. We did not spring ready-made into the twenty-first century. The human female is born and bred to select a mate, have babies, nurture them and, having completed this task, die. That is why we adorn ourselves, sweep the cave, attract the best man we can, spite unsuccessful lovers, fall in love and keep a man at our side as long as we can. We are hardwired to do it, for the sake of our children.

Whether a woman wants babies or not, whether she has them or not, is irrelevant. Her physiology and her emotions behave as if she does. Her hormones are all set up to make her behave like a female member of the tribe. The female brain differs from the male even in appearance. Pathologists can tell which is which just by looking,

(Of course if a woman doesn’t want to put up with her female destiny she can take testosterone in adult life and feel and be more like a man. Though it is better, I feel, to work with what you have. And that early foetal drenching in oestrogen, when the female foetus decides at around eight weeks that female is the way it’s going to stay, is pretty final.)

In her young and fecund years a woman must call upon science and technology, or great self-control, in order not to get pregnant. As we grow older, as nurture gains more power over nature, it becomes easier to avoid it. A: We are less fertile. B: We use our common sense. The marvel is that there are so few teenage pregnancies, not so many.

To fall in love is to succumb to instinct. Common sense may tell us it’s a daft thing to do. Still we do it. We can’t help it, most of us, once or twice in a lifetime. Oestrogen levels soar, serotonin plummets. Nature means us to procreate.

(Odd, the fall in serotonin symptomatic of falling in love. Serotonin, found in chocolate, makes us placid and receptive. A serotonin drop make us anxious, eager, sexy and on our toes. Without serotonin, perhaps, we are more effective in courtship.)

Following the instructions of the blueprint for courtship, the male of the human species open doors for us, bring us gifts and forages for us. If he fails to provide, we get furious, even when we ourselves are the bigger money earners. We batter on the doors of the CSA. It’s beyond all reason. It is also, alas, part of the male impulse to leave the family as soon as the unit can survive without him and go off and create another. (Now that so many women can get by perfectly well without men, the surprise is that men stay around at all.)

The tribe exercises restraint upon the excesses of the individual, however, and so we end up with marriage, divorce laws, sexual-harassment suits and child support. The object of our erotic attention also has to conform to current practices, no matter what instinct says. ‘Under 16? Too bad!’ ‘Your pupil? Bad luck!’ Nature says, ‘Kill the robber, the interloper.’ Nurture says, ‘No, call the police.’ The sanction, the disapproval of the tribe, is very powerful. Exile is the worst fate of all. Without the protection of the tribe, you die.

Creatures of the Tribe

We do not define ourselves by our animal nature. We are more than creatures of a certain species. We are moral beings. We are ingenious and inquisitive, have intelligence, self-control and spirituality. We understand health and hormones. We develop technology to make our lives easier. We live far longer, thanks to medical science, than nature, left to its own devices, would have us do. We build complicated societies. Many of us choose not have babies, despite our bodies’ instinctive craving for them. We socialize men not to desert us; we also, these days, socialize ourselves not to need them.

‘I don’t dress to attract men,’ women will say. ‘I dress to please myself.’ But the pleasure women have in the candlelit bath before the party, the arranging and rearranging of the hair, the elbowing of other women at the half-price sale, is instinctive. It’s an overflow from courting behaviour. It’s also competitive, whether we admit it or not. ‘I am going to get the best man. Watch out, keep off!’

To make friends is instinctive. We stick to our age groups. We cluster with the like-minded. That way lies the survival of the tribe. A woman needs friends to help her deliver the baby, to stand watch when the man’s away. But she must also be careful: other women can steal your alpha male and leave you with a beta.

See in shopping, source of such pleasure, also the intimidation of rivals. ‘My Prada handbag so outdoes yours – crawl away!’ And she will, snarling.

And if her man’s genes seem a better bet than your man’s, nab him. Nature has no morality.

Any good feminist would dismiss all this as ‘biologism’ – the suggestion that women are helpless in the face of their physiology. Of course we are not, but there’s no use denying it’s at the root of a great deal of our behaviour, and indeed of our miseries. When instincts conflict with each other, when instinct conflicts with socialization, when nature and nurture pull us different ways, that’s when the trouble starts.

‘I want another éclair.’

Agony.

Well, take the easy way out. Say to yourself, ‘One’s fine, two’s not.’ No one’s asking for perfection. And anxiety is inevitable.

A parable.

Once Bitten, Twice Shy

Picture the scene. It’s Friday night. David and Letty are round at Henry and Mara’s place, as is often the case, sharing a meal. They’re all young professionals in their late twenties, good-looking and lively as such people are. They’ve unfrozen the fish cakes, thawed the block of spinach and cream, and Henry has actually cleaned and boiled organic potatoes. After that it’s cheese, biscuits and grapes. Nothing nicer. And Mara has recently bought a proper dinner set so the plates all match.

They all met at college. Now they live near each other. They’re not married, they’re partnered. But they expect and have so far received fidelity. They have all even made quasi-nuptial contracts with their partner, so should there be a split the property can be justly and fairly assigned. All agree the secret of successful relationships is total honesty.

After graduation Henry and Mara took jobs with the same city firm so as to be together. Mara is turning out to be quite a highflyer. She earns more than Henry does. That’s okay. She’s bought herself a little Porsche, buzzes around. That’s fine.

‘Now I can junk up the Fiesta with auto mags, gum wrappers and Coke tins without Mara interfering,’ says Henry.

Letty and David work for the same NHS hospital. She’s a radiographer; he is a medical statistician. Letty is likely to stay in her job, or one like it, until retirement, gradually working her way up the promotional ladder, such is her temperament. David is more flamboyant. He’s been offered a job at New Scientist. He’ll probably take it.

Letty would like to get pregnant, but they’re having difficulty and Letty thinks perhaps David doesn’t really want a baby, which is why it isn’t happening.

Letty does have a small secret from David. She consults a psychic, Leah, on Friday afternoons when she leaves work an hour earlier than on other days. She doesn’t tell David because she thinks he’d laugh.

‘I see you surrounded by babies,’ says Leah one day, after a leisurely gaze into her crystal ball.

‘Fat chance,’ says Letty.

‘Is your husband a tall fair man?’ asks Leah.

‘He isn’t my husband, he’s my partner,’ says Letty crossly, ‘and actually he’s rather short and dark.’

Leah looks puzzled and changes the subject.

But that was a couple of weeks back. This is now. Two bottles of Chilean wine with the dinner, a twist of weed which someone gave Mara for a birthday present…and which they’re not sure they’ll use. They’re happy enough as they are. Medical statisticians, in any case, do not favour the use of marijuana.

Henry owns a single e, which someone for reasons unknown gave him when Mara bought the Porsche, saying happiness is e-shaped. He keeps it in his wallet as a kind of curiosity, a challenge to fate.

‘You’re crazy,’ says Letty, when he brings it out to show them. ‘Suppose the police stopped you? You could go to prison.’

‘I don’t think it’s illegal to possess a single tablet,’ says David. ‘Only to sell them.’

He is probably right. Nobody knows for sure. Henry puts it away. It’s gone kind of greyish and dusty from too much handling, anyway, and so much observation. Ecstasy is what other people do.

Mara’s mobile sings ‘Il Toreador’. Mara’s mother has been taken ill at home in Cheshire. It sounds as if she might have had a stroke. She’s only 58. The ambulance is on its way. Mara, who loves her mother dearly, decides she must drive north to be there for her. No, Mara insists, Henry isn’t to come with her. He must stay behind to hold the fort, clear the dinner, make apologies at work on Monday if it’s bad and Mara can’t get in. ‘You’d only be in the way,’ she adds. ‘You know what men are like in hospitals.’ That’s how Mara is: decisive. And now she’s on her way, thrum, thrum, out of their lives, in the Porsche.

Now there are only Henry, David and Letty to finish the second bottle. David’s phone sings ‘Ode to Beauty’ as the last drop is drained. To open another bottle or not to open another bottle – that’s the discussion. Henry opens it, thus solving the problem. It’s David’s father. There’s been a break-in at the family home in Cardiff, the robbers were disturbed and now the police are there. The digital camera has gone and 180 photos of sentimental value and some jewellery and a handbag. David’s mother is traumatized and can David make it to Cardiff for the weekend?

‘Of course,’ says David.

‘Can I come?’ asks Letty, a little wistfully. She doesn’t want to be left alone.

But David says no, it’s a long drive, and his parents and the Down’s sister will be upset and he’ll need to concentrate on them. Better for Letty to stay and finish the wine and Henry will walk her home.

Letty feels more than a little insulted. Doesn’t it even occur to David to feel jealous? Is it that he trusts Letty or that he just doesn’t care what happens to her? And is he really going to Cardiff or is he just trying to get away from her? Perhaps he has a mistress and that’s why he doesn’t want to have a baby by her.

David goes and Letty and Henry are left together, both feeling abandoned, both feeling resentful.

Henry and Letty are the ones who love too much. Mara and David love too little. It gives them great power. Those who love least win.

Henry and Letty move out onto the balcony because the evening is so warm and the moon so bright they hardly need a candle to roll the joint. On warm days Mara likes to sit on this balcony to dry her hair. She’s lucky. All Mara has to do is dunk her hair in the basin and let it dry naturally and if falls heavy and silky and smooth. Mara is so lucky in so many respects.

And now Henry walks over to where Letty sits in the moonlight, all white silky skin and bare shoulders and pale-green linen shift which flatters her slightly dull complexion, and slides his hands over her shoulders and down almost to where her breasts start and then takes them away.

‘Sorry,’ he says. ‘I shouldn’t have done that.’

‘No, you shouldn’t,’ she says.

‘I wanted to,’ he said.

‘I wanted you to do it too. I think it’s the moon. Such a bright night. And see, there’s Venus beside her, shining bright.’

‘Good Lord!’ he says. ‘Think of the trouble!’

‘But life can get kind of boring,’ Letty says. She, the little radiographer, wants her excitements too. Thrum, thrum, thrum goes Mara, off in the Porsche! Why shouldn’t it be like that for Letty too? She deserves Henry. Mara doesn’t. She’d be nice to him. Letty’s skin is still alive to his touch and wanting more.

‘But we’re not going to, are we?’ he says.

‘No,’ says Letty. ‘Mara’s my friend.’

‘More to the point,’ he says, ‘David’s your partner.’

They think about this for a little while.

‘Cardiff and Cheshire,’ says Letty. ‘Too good to be true. That gives us all night.’

‘Where?’ asks Henry.

‘Here,’ says Letty.

All four have in the past had passing fantasies about what it would be like to share a bed and a life with the other – have wondered if, at the student party where they all met, Henry had paired off with Letty, David with Mara, what their lives would have been like. The fantasies have been quickly subdued in the interests of friendship and expediency. But Mara’s sheets are more expensive than Letty’s, her bed is broader. The City pays more than the NHS. Letty would love to sleep in Mara’s bed.

‘We could go to your place,’ says Henry. To elbow David out of his own bed would be very satisfactory. Henry is stronger and taller than David; Henry takes what he wants when he wants it. Henry has wit and cunning, the kind which enables you to steal another man’s woman from under his nose.

But Letty’s envy is stronger than Henry’s urge to crush his rivals. They agree to stay where they are. They agree this is greater than either of them. They share the e, looking into each other’s eyes as if they were toasting one another in some foreign land. It is in fact an aspirin, but since they both believe it’s ecstasy, it has the effect of relieving themselves of responsibility for their own actions. Who, drug-crazed, can help what they do?

They tear off each other’s clothes. Mara’s best and most seductive apricot chiffon nightie is under the pillow. Letty puts it on. Henry makes no objection. It is the one Mara wears, he has come to believe, when she means to refuse him. Too tired, too cross, just not interested. He pushes the delicate fabric up over Letty’s thighs with even more satisfaction. He doesn’t care if he tears it.

‘Shouldn’t you be wearing a condom?’ she asks.

‘I don’t like them,’ he says.

‘Neither do I,’ she says.

For ten minutes Letty is supremely happy. The dark, rich places of the flesh unfold and surround her with forgetfulness. She is queen of all places and people. She can have as many men as she wants, just snap her fingers and there they are. She has infinite power. She feels wholly beautiful, consummately desired, part of the breathing, fecund universe, at one with the Masai girl, the Manhattan bride, every flower that ever stooped to mix its pollen, every bird that sings its joy to heaven. And every one of Henry’s plunges is a delightful dagger in Mara’s heart, his every powerful thrust a reproach to pallid, cautious David.

Then Letty finds herself shifting out of a blissful present into a perplexing future. She’s worrying about the sheets. This is condom-less sex. What about stains? Will Mara notice? She could launder them – there’s a splendid washer-dryer in the utility room, but supposing it broke down mid-wash? Henry could possibly argue that he spilt wine on the sheets – as indeed he has, and honey too, now she comes to think of it. She is very sticky. Can Mara’s chiffon nightie be put in the machine or must it be hand washed?

‘Is something the matter?’ he asks.

‘No,’ she says.

But she no longer feels safe. Supposing Mara gets a call from her family on the way to Cheshire and turns back? Supposing she and Henry are discovered? Why is she doing this? Is she mad?

Her body shudders in spite of herself. She rather resents it. An orgasm crept up on her when she was trying to concentrate on important things. She decides sex is just mechanical. She’d rather have David, anyway. His penis is less effective and smaller than Henry’s, but it’s familiar and feels right. David must never find out about this. Perhaps she doesn’t want a baby as much as thought she did. In any case she can’t have a baby that isn’t David’s. What if she got pregnant now? She’d have to have an abortion, and it’s against her principles, and it would have to be secret because fathers can now claim rights to unborn embryos.

Henry rolls off her. Letty makes languid disappointment noises but she’s rather relieved. He is heavier than David.

Henry’s phone goes. He answers it. Mara is stuck behind an accident on the M6 north of Manchester,

‘Yes,’ says Henry, ‘I walked Letty home.’

Now Letty’s cross because Henry has denied her. Secrecy seems sordid. And she hates liars. And Mara? What about Mara? Mara is her friend. They’re studied together, wept together, bought clothes together and supported each other through bad times, good times. Mara and her Porsche and her new wardrobe have all seemed a bit much, true, but she sees why Mara puts Henry down from time to time. He’s not only irritating but untrustworthy. How could you trust your life to such a man? She ought to warn Mara about that, but how can she? Poor Mara, stuck behind an ambulance in the early hours in the far north while her partner betrays her with her best friend…

Henry is licking honey off his fingertips suggestively. ‘Shall we do that again?’ he asks. ‘Light of my life.’

‘No,’ says Letty and rolls out of bed. Her bare sticky feet touch the carpet and she is saved.

Moral

Few of us can resist temptation the first

time round, and we should not blame

ourselves too much if we fail. It’s the

second time that counts. Let sin pass

lightly on and over. Persist in it and it

wears your soul away.

Letty’s sense of guilt evaporates, washed away in the knowledge of her own virtue and fondness for her friend. Guilt is to the soul as pain is to the body. It is there to keep us away from danger, from extinction.

And good Lord, think what might have happened had Letty stayed for a second round! As it was she got into her own bed just minutes before David came through the door. His father had rung from Cardiff and the jewellery had been found and the burglary hadn’t happened after all. Letty hadn’t had a bath, thinking she’d leave that until the morning, but David didn’t seem to notice. Indeed, he fell on her with unusual ardour and the condom broke and he didn’t even seem to mind.

If she’d stayed in Mara’s bed David would have come round to find Letty and at worst killed Henry – fat chance! – and at best told Mara, or if not that then he’d have been able to blackmail Letty for the rest of her life. ‘Do this or I’ll tell Mara’ – and she’d have had to do it, whatever it was: go whoring, get a further degree (not that there wasn’t some attraction in surrendering autonomy…)

The free sample has ended.