This book cannot be downloaded as a file but can be read in our app or online on the website.

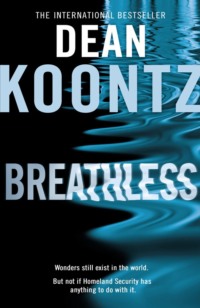

Read the book: «Breathless»

DEAN KOONTZ

Breathless

Dedication

To Aesop, twenty-six centuries late and with apologies for the length.

And as always and forever to Gerda

Epigraph

Science must not impose any philosophy, any more than the telephone must tell us what to say.

–G.K. Chesterton

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One: Life and Death

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Part Two: Death in Life

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-One

Chapter Sixty-Two

Chapter Sixty-Three

Part Three: Life in Death

Chapter Sixty-Four

Chapter Sixty-Five

Chapter Sixty-Six

Chapter Sixty-Seven

Chapter Sixty-Eight

Chapter Sixty-Nine

Chapter Seventy

Chapter Seventy-One

Chapter Seventy-Two

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PART ONE Life and Death

Chapter One

A moment before the encounter, a strange expectancy overcame Grady Adams, a sense that he and Merlin were not alone.

In good weather and bad, Grady and the dog walked the woods and the meadows for two hours every day. In the wilderness, he was relieved of the need to think about anything other than the smells and sounds and textures of nature, the play of light and shadow, the way ahead, and the way home.

Generations of deer had made this path through the forest, toward a meadow of grass and fragrant clover.

Merlin led the way, seemingly indifferent to the spoor of the deer and the possibility of glimpsing the white flags of their tails ahead of him. He was a three-year-old, 160-pound Irish wolfhound, thirty-six inches tall, measured from his withers to the ground, his head higher on a muscular neck.

The dog’s rough coat was a mix of ash-gray and darker charcoal. In the evergreen shadows, he sometimes seemed to be a shadow, too, but one not tethered to its source.

As the path approached the edge of the woods, the sunshine beyond the trees suddenly looked peculiar. The light turned coppery, as if the world, bewitched, had revolved toward sunset hours ahead of schedule. With a sequined glimmer, afternoon sun shimmered down upon the meadow.

As Merlin passed between two pines, stepping onto open ground, a vague apprehension – a presentiment of pending contact – gripped Grady. He hesitated in the woodland gloom before following the dog.

In the open, the light was neither coppery nor glimmering, as it had appeared from among the trees. The pale-blue arch of sky and emerald arms of forest embraced the meadow.

No breeze stirred the golden grass, and the late-September day was as hushed as any vault deep in the earth.

Merlin stood motionless, head raised, alert, eyes fixed intently on something distant in the meadow. Wolfhounds were thought to have the keenest eyesight of all breeds of dogs.

The back of Grady’s neck still prickled. The perception lingered that something uncanny would occur. He wondered if this feeling arose from his own intuition or might be inspired by the dog’s tension.

Standing beside the immense hound, seeking what his companion saw, Grady studied the field, which gently descended southward to another vastness of forest. Nothing moved … until something did.

A white form, supple and swift. And then another.

The pair of animals appeared to be ascending the meadow less by intention than by the consequence of their play. They chased each other, tumbled, rolled, sprang up, and challenged each other again in a frolicsome spirit that could not be mistaken for fighting.

Where the grass stood tallest, they almost vanished, but often they were fully visible. Because they remained in motion, however, their precise nature was difficult to define.

Their fur was uniformly white. They weighed perhaps fifty or sixty pounds, as large as midsize dogs. But they were not dogs.

They appeared to be as limber and quick as cats. But they were not cats.

Although he’d lived in these mountains until he was seventeen, though he had returned four years previously, at the age of thirty-two, Grady had never before seen creatures like these.

Powerful body tense, Merlin watched the playful pair.

Having raised him from a pup, having spent the past three years with little company other than the dog, Grady knew him well enough to read his emotions and his state of mind. Merlin was intrigued but puzzled, and his puzzlement made him wary.

The unknown animals were large enough to be formidable predators if they had claws and sharp teeth. At this distance, Grady could not determine if they were carnivores, omnivores, or herbivores, though the last classification was the least likely.

Merlin seemed to be unafraid. Because of their great size, strength, and history as hunters, Irish wolfhounds were all but fearless. Although their disposition was peaceable and their nature affectionate, they had been known to stand off packs of wolves and to kill an attacking pit bull with one bite and a violent shake.

When the white-furred creatures were sixty or seventy feet away, they became aware of being watched. They halted, raised their heads.

The birdless sky, the shadowy woods, and the meadow remained under a spell of eerie silence. Grady had the peculiar notion that if he moved, his boots would press no sound from the ground under him, and that if he shouted, he would have no voice.

To get a better view of man and dog, one of the white creatures rose, sitting on its haunches in the manner of a squirrel.

Grady wished he had brought binoculars. As far as he could tell, the animal had no projecting muzzle; its black nose lay in nearly the same plane as its eyes. Distance foiled further analysis.

Abruptly the day exhaled. A breeze sighed in the trees behind Grady.

In the meadow, the risen creature dropped back onto all fours, and the pair raced away, seeming to glide more than sprint. Their sleek white forms soon vanished into the golden grass.

The dog looked up inquiringly. Grady said, “Let’s have a look.”

Where the mysterious animals had gamboled, the grass was bent and tramped. No bare earth meant no paw prints.

Merlin led his master along the trail until the meadow ended where the woods resumed.

A cloud shadow passed over them and seemed to be drawn into the forest as a draft draws smoke.

Gazing through the serried trees into the gloom, Grady felt watched. If the white-furred pair could climb, they might be in a high green bower, cloaked in pine boughs and not easily spotted.

Although he was a hunter by breed and blood, with a Sherlockian sense of smell that could follow the thinnest thread of unraveled scent, Merlin showed no interest in further pursuit.

They followed the tree line west, then northwest, along the curve of meadow, circling toward home as the quickening air whispered through the grass. They returned to the north woods.

Around them, the soft chorus of nature arose once more: birds in song, the drone of insects, the arthritic creak of heavy evergreen boughs troubled by their own weight.

Although the unnatural hush had relented, Grady remained disturbed by a sense of the uncanny. Every time he glanced back, no stalker was apparent, yet he felt that he and Merlin were not alone.

On a long rise, they came to a stream that slithered down well-worn shelves of rock. Where the trees parted, the sun revealed silver scales on the water, which was elsewhere dark and smooth.

With other sounds masked by the hiss and gurgle of the stream, Grady wanted more than ever to look back. He resisted the paranoid urge until his companion halted, turned, and stared downhill.

He did not have to crouch in order to rest one hand on the wolfhound’s back. Merlin’s body was tight with tension.

The big dog scanned the woods. His high-set ears tipped forward slightly. His nostrils flared and quivered.

Merlin held that posture for so long, Grady began to think the dog was not so much searching for anything as he was warning away a pursuer. Yet he did not growl.

When at last the wolfhound set off toward home once more, he moved faster than before, and Grady Adams matched the dog’s pace.

Chapter Two

Authorities raided the illegal puppy mill late Saturday afternoon. Saturday night, Rocky Mountain Gold, an all-volunteer golden-retriever rescue group, took custody of twenty-four breeder dogs that were filthy, malnourished, infested with ticks, crawling with fleas, and suffering an array of untreated infections.

Dr. Camillia Rivers was awakened by a call on her emergency line at 5:05 Sunday morning. Rebecca Cleary, president of Rocky Mountain Gold, asked how many of the twenty-four Cammy might treat in return for nothing but the wholesale cost of what drugs were used.

After looking at the nightstand photo of her golden, Tessa, who had died only six weeks earlier, Cammy said, “Bring ’em all.”

Her business partner and fellow vet, Donna Corbett, was in the middle of a one-week vacation. Their senior vet tech, Cory Hern, had gone to visit relatives in Denver for the weekend. When she called the junior tech, Ben Aikens, he agreed to donate his Sunday to the cause.

At 6:20 A.M., a Rocky Mountain Gold caravan of SUVs arrived at the modest Corbett Veterinary Clinic with twenty-four goldens in as desperate condition as any Cammy had ever seen. Every one was potentially a beautiful dog, but at the moment they looked like the harbingers of Armageddon.

Having endured their entire lives in cramped cages, not merely neglected but also abused, having been forced without vet care to bear litter after litter to the point of exhaustion, they were timid, trembling, vomiting in fear, frightened of everyone they encountered. In their experience, human beings were cruel or at best indifferent to them, and they expected to be struck.

Eight members of the rescue group assisted with bathing, shaving fur away from hot spots and other sores, clipping knots out of coats, deticking, and other tasks, all of which were complicated by the need continually to calm and reassure the dogs.

Cammy was unaware that the morning had passed until she checked her wristwatch at 2:17 in the afternoon. Having skipped breakfast, she took a fifteen-minute break and retreated to her apartment above the veterinary facility, to have a bite of lunch.

For a long time, Donna Corbett had run the practice with her husband, John, who was also a veterinarian. When John died of a heart attack four years earlier, Donna divided their large apartment into two units and sought a partner who would be as committed to animals as she was and as John had been, who was willing to live the work.

The Corbetts viewed veterinary medicine less as a profession than as a calling, which was why Cammy didn’t need to consult with her partner when agreeing to treat the puppy-mill dogs pro bono.

After quickly putting together a cheese sandwich, she opened a cold bottle of tea sweetened with peach nectar. She ate lunch while standing at her kitchen sink.

As she’d been working with the folks from Rocky Mountain Gold, two calls had come in, one regarding a sick cow. She referred the caller to Dr. Amos Renfrew, who was the best cow doc in the county.

The second inquiry came from Nash Franklin, regarding a horse at High Meadows Farm. Because the situation wasn’t urgent, Cammy would pay Nash a visit later in the afternoon.

She had nearly finished the cheese sandwich when Ben Aikens, her vet tech, rang her from downstairs. “Cammy, you’ve got to see this.”

“What’s wrong?”

“These dogs. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

“Be right there.” She shoved the last piece of the sandwich into her mouth and chewed it on the run.

Puppy-mill breeders were routinely so physically and emotionally traumatized by their abuse that the new experiences of freedom – open spaces; cars; steps, which they never before climbed or descended; strange noises; soap and water; even kind words and gentle touching – could induce a dangerous state of shock. Most often, the cause of shock was chronic dehydration or untreated infections, but there were times when Cammy could attribute it to nothing else but the impact of the new, of change.

If they could be cured of their diseases and conditions, the dogs would need months of socializing, but in time they would find their courage, regain the joyful spirit that defined a golden, and learn to trust, to love, to be loved.

Descending the exterior stairs from her apartment, she prayed that all these dogs might survive and thrive, that not one of them would be lost to infection or disease, or shock.

Cammy entered the clinic by the front door. She hurried through the small waiting room, along a hallway flanked by four examination cubicles, and through a swinging door into the large, tile-floored open space that included treatment stations and grooming facilities.

Awaiting her was a sight far different from the crisis she had anticipated. Every one of these brutalized dogs appeared to have shed its anxiety, to have suppressed already the memories of torment in favor of embracing a new life. Tails wagging, eyes bright, grinning that fabled golden grin, they submitted happily to belly rubs and ear scratches from the Rocky Mountain Gold volunteers. They nuzzled one another and explored the room, sniffing this and that, curious about things that a short while ago frightened them. None lay in cataplexic collapse or hid its face, or cowered, or trembled.

This unlikely sight had startled Cammy to a stop. Now, as she moved farther into the room, Ben Aikens hurried to her.

Ben, twenty-seven, had a perpetually sunny disposition, but even for him, his current mood seemed unusually buoyant. He was virtually shining with delight. “Isn’t it fantastic? You ever seen anything like it? Have you, Cammy?”

“No. Never. What happened here?”

“We don’t know. The dogs were like before, anxious, distressed, so pitiful. Then they – Well, they – They went still and quiet, all of them at once. They lifted their ears, all of them listening, and they heard something.”

“Heard what?”

“I don’t know. We didn’t hear it. They raised their heads. They all stood up. They stood so still, motionless, they heard something.”

“What were they looking at?”

“Nothing. Everything. I don’t know. But look at them now.”

Cammy reached the center of the room. The rescued animals were everywhere engaged in the spirited behavior of ordinary dogs.

When she knelt, two goldens came to her, tails wagging, seeking affection. Then another and another, and a fifth. Sores, scars, ear-flap hematomas, fly-bite dermatitis: None of that seemed to matter to the dogs anymore. This one was half blind from an untreated eye infection, that one limped from patellar dislocation, but they seemed happy, and they were uncomplaining. Ragged, tattered, gaunt, freed from a life of cruelty and abuse less than twenty-four hours earlier, they were suddenly and inexplicably socialized, neither afraid any longer nor timid.

Rebecca Cleary, head of the rescue group, knelt beside Cammy. “Pinch me. This has got to be a dream.”

“Ben says they all stood up at once, listening to something.”

“At least a minute. Listening, alert. We weren’t even there.”

“What do you mean?”

“Like they weren’t aware of us anymore. Almost … in a trance.”

Cammy held a retriever’s head in her cupped hands, rubbing its flews with her thumbs. The dog, so recently fearful and shy, accepted the face massage with pleasure, met her eyes, and did not look away.

“At first,” Rebecca said, “it was eerie …”

The animal’s eyes were as golden as its coat.

“… then they became aware of us again, and it was wonderful.”

The dog’s eyes were as bright as gems. Topaz. They seemed to have an inner light. Eyes of great beauty – clear, direct, and deep.

Chapter Three

The unpaved turnoff was where he expected to find it, two hundred yards past Milepost 76 on the state highway. He coasted almost to a stop, afraid that his hopes would not be fulfilled, but then he wheeled the Land Rover right, onto the one-lane road.

Henry Rouvroy had not seen his twin brother, James, for fifteen years. He was nervous but inexpressibly happy about the prospect of their reunion.

Their lives had followed different paths. So much time passed so quickly.

At first, when the idea to reconnect with Jim came to Henry, he dismissed it. He worried that he wouldn’t be met with hospitality.

They had never experienced the fabled psychic connection of identicals. On the other hand, they had never been at odds with each other, either. There was no bad blood between them, no bitterness.

They had simply been different from each other, interested in different things. Even in childhood, Henry was the social twin, always in a group of friends. Jimmy preferred solitude. Henry thrived on sports, games, action, challenges. Jimmy was content with books.

When their parents divorced, they were twelve. Instead of sharing custody of both boys, their father took Henry to New York to live with him, and their mother settled in a small town in Colorado with Jimmy, which seemed right and natural to everyone.

Since they were twelve, they had seen each other only once, when they were twenty-two, at the reading of their father’s will. Their mother died of cancer a year before the old man passed away.

They agreed to stay in touch. Henry wrote five letters to his brother over the following year, and Jim answered two of them. Thereafter, Henry wrote less often, and Jim never again replied.

Although they were brothers, Henry accepted that they were also virtually strangers. As much as he might want to be part of a closely knit family, it was not to be.

But by nature, the human heart yearns most for what it cannot have. Time and circumstances brought Henry here to rural Colorado, with the hope that their relationship might change.

Pines crowded close to the road, and branches swagged within inches of the roof. Even in daytime, headlights were needed.

Years earlier, the University of Colorado had owned this land. Jim’s remote house had been occupied by a series of researchers who studied conifer ecology and tested theories of forest management.

The hard-packed earth gave way to shale in places, and nine-tenths of a mile from the paved highway, at the end of the lane, Henry arrived at his brother’s property.

The one-story clapboard house had a deep porch with a swing and rocking chairs. Although modest, it looked well-maintained and cozy.

Willows and aspens shaded the residence.

Henry knew that the clearing encompassed six acres of sloping fields, because “Six Acres” was the title of one of his brother’s poems. Jim’s writing had appeared in many prestigious journals, and four slender volumes of his verse had been published.

No one made money from poetry anymore. Jim and his wife, Nora, worked their six acres as a truck farm during the growing season, selling vegetables from a booth at the county farmer’s market.

Attached to the barn were a large coop and fenced chicken yard. A formidable flock shared the yard in good weather, kept to the well-insulated coop in winter, producing eggs that Jim and Nora also sold.

She was a quilter of such talent that her designs were regarded as art. Her quilts sold in galleries, and Henry supposed she produced the larger part of their income, though they were by no means rich.

Henry knew all of that from reading his brother’s poems. Hard work and farm life provided the subjects of the verses. Jim was the latest in a long tradition of American literary rustics.

Following the dirt track between the house and the barn, Henry saw his brother splitting cordwood with an axe. A wheelbarrow full of split wood stood nearby. He parked and got out of the Land Rover.

Jim sunk the axe blade in the stump that he used as a chopping block, and left it wedged there. Stripping off his worn leather work gloves, he said, “My God – Henry?”

His look of incredulity was less than the delight for which Henry had hoped. But then he broke into a smile as he approached.

Reaching out to shake hands, Henry was surprised and pleased when Jim hugged him instead.

Although Henry worked out with weights and on a treadmill, Jim was better muscled, solid. His face was more weathered than Henry’s, too, and still tanned from summer.

Nora came out of the house, onto the porch, to see what was happening. “Good Lord, Jim,” she said, “you’ve cloned yourself.”

She looked good, with corn-silk hair and eyes a darker blue than the sky, her smile lovely, her voice musical.

Five years younger than Jim, she had married him only twelve years ago, according to the author’s bio on the poetry books. Henry had never met her or seen a photograph of her.

She called him Claude, but he quickly corrected her. He never used his first name, but instead answered to his middle.

When she kissed his cheek, her breath smelled cinnamony. She said she’d been nibbling a sweetroll when she heard the Land Rover.

Inside, on the kitchen table, beside the sweetroll plate were what Henry assumed to be five utility knives, useful for farm tasks.

As Nora poured coffee, she said nothing about the knives. Neither did Jim as he moved them – and two slotted sharpening stones – from the table to a nearby counter.

Nora insisted that Henry stay with them, though she warned him that a sofa bed was all they had by way of accommodations, in the claustrophobic room that Jim called an office.

“Haven’t had a houseguest in nine years,” Jim said, and it seemed to Henry that a knowing look passed between husband and wife.

The three of them fell into easy conversation around the kitchen table, over homemade cinnamon rolls and coffee.

Nora proved charming, and her laugh was infectious. Her hands were strong and rough from work, yet feminine and beautifully shaped.

She had nothing in common with the sharky women who cruised in Henry’s circle in the city. He was happy for his brother.

Even as he marveled at how warmly they welcomed him, at how they made him feel at home and among family, as he had never felt with Jim before, Henry was not entirely at ease.

His vague disquiet arose in part from his perception that Jim and Nora were in a private conversation, one conducted without words, with furtive looks, nuanced gestures, and subtle body language.

Jim expressed surprise that someone had drawn Henry’s attention to his poetry. “Why would they think we were related?”

They didn’t share the name Rouvroy. Following their parents’ divorce, Jim had legally taken his mother’s maiden name, Carlyle.

“Well,” Henry said drily, “maybe it was your photo on the book.”

Jim laughed at his thickheadedness, and although he seemed to be embarrassed by his brother’s praise, they talked about his poems. Henry’s favorite, “The Barn,” described the humble interior of that structure with such rich images and feeling that it sounded no less beautiful than a cathedral.

“The greatest beauty always is in everyday things,” Jim said. “Would you like to see the barn?”

“Yes, I would.” Henry admired his brother’s poetry more than he had yet been able to say. Jim’s verses had an ineffable quality so haunting it was not easy to discuss. “I’d like to see the barn.”

Clearly in love with this piece of the world that he and Nora had made their own, Jim grinned, nodded, and rose from the table.

Nora said, “I’ll put linens on the sofa bed and start thinking about what’s for dinner.”

Following Jim from the kitchen, Henry glanced at the knives on the counter. On second consideration, they looked less like ordinary task knives than like thrust-and-cut weapons. The four- and five-inch blades had nonreflective finishes. Two seemed to feature assisted-opening mechanisms for quick blade release.

Then again, Henry knew nothing about farming. These knives might be standard stock at any farm-supply store.

Outside, the afternoon air remained mild. From the split cords of pine came the scent of raw wood.

Overhead, two magnificent birds with four-foot wingspans glided in intersecting gyres. The ventral feathers of the first were white with black wing tips. The second was boldly barred in white and brown.

“Northern harriers,” Jim said. “The white one with the black tips is the male. Harriers are raptors. When they’re hunting, they fly low over the fields and kill with a sudden pounce.”

He worked the axe loose from the tree-stump chopping block.

“Better put this away in the barn,” he said, “before I forget and leave it overnight.”

“Harriers,” Henry said. “They’re so beautiful, you don’t think of them as killing anything.”

“They eat mostly mice,” Jim said. “But also smaller birds.”

Henry grimaced. “Cannibalism?”

“They don’t eat other harriers. Their feeding on smaller birds is no more cannibalism than us feeding on other mammals – pigs, cows.”

“Living in the city, I guess we idealize nature,” Henry said.

“Well, when you accept the way of things, there’s a stark kind of beauty in the dance of predators and prey.”

Heading to the barn, Jim carried the axe in both hands, as if to raise and swing it should he see something that needed to be chopped.

The harriers had fled the sky.

When Henry glanced back toward the house, he saw Nora watching them from a window. With her pale hair and white blouse, she looked like a ghost behind the glass. She turned away.

“Life and death,” Jim said as they drew near the barn.

“Excuse me?”

“Predators and prey. The necessity of death, if life is to have meaning and proportion. Death as a part of life. I’m working on a series of poems with those themes.”

Jim opened the man-size entrance beside the pair of larger barn doors. Henry followed his brother into the wedge of sunshine that the door admitted to this windowless and otherwise dark space.

Inside, in the instant before the lights came on, Henry was gripped by the expectation that before him would be some sight for which Jim’s poem had not prepared him, that the poem was a lie, that the truck farming and the quilting and the simple-folks image were all lies, that the reality of this place and these people was more terrible than anything he could imagine.

When Jim threw a switch, a string of bare light bulbs brightened the length of that cavernous space, revealing the barn to be nothing more than a barn. A tractor and a backhoe were garaged on the left. Two horses occupied stalls on the right. The air was fragrant with the scents of hay and feed grain.

Although Henry’s alarming premonition had proved false, and although he knew that fearing his brother was as absurd as fearing the tractor or the horses, or the smell of hay, his sense of a nameless impending horror did not abate.

Behind him, the barn door swung shut of its own weight.

Jim turned to him with the axe, and Henry shrank back, and Jim stepped past him to hang the axe on a rack of tools.

Heart racing, breath suddenly ragged, Henry drew the SIG P245 from the snugly fit shoulder rig under his jacket and shot his twin point-blank, twice in the chest and once in the face.